The Taxation Of Artificial Intelligence(AI): If, Why, When And How?

Monday, 12 August 2024By Bob McDowall

Introduction

Research on automation generally and specifically through artificial intelligence have an impact on the formulation of tax policy, but research on AI, automation and applicable taxation policies are at a very early era.

Of course, the economic impact of new technologies is relevant to the taxation of labour and capital but the impact has to be viewed in the wider contexts: the impacts of AI on economic efficiency include the AI share of capital income in national income, the distribution of wage and capital income, and the impact of the tax system on work incentives such as research and development, job creation and entrepreneurship.

Cash strapped Governments are always on the lookout for new forms of taxation and new forms of business to tax, which extend beyond the application of conventional corporate dividend, income and capital gains taxation.

The questions Governments continually have to ask are “if, why, when and how?”

If

AI is but one element of digital transformation of work, leisure and society, albeit at the centre of digital transformation for the past 5-10 years. Digital transformation is slower in deployment in some geographic regions and sectors, and faster in others.

The big “if” question is to determine whether taxation policy has a very specific purpose in deployment of AI technology? How should taxes on labour and capital be designed to promote AI driven growth but ensure that positive economic effects are distributed as widely as possible? How can the harmful effects be discouraged by punitive taxation, as well as legislative discouragement and outright prohibition?

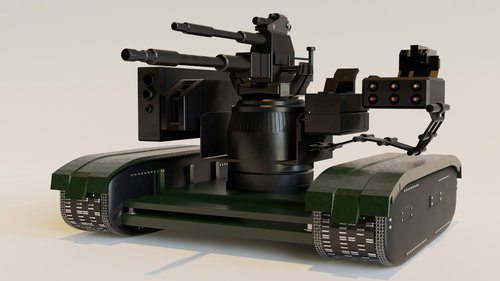

Whilst the positive economic benefits of AI include a reduction in the time taken to perform tasks, the performance of complex tasks without significant cost outlays, and continuous operation without interruption or breaks (downtime), harmful effects could include breaches of privacy, socio-economic inequality, unemployment, systemic risks, algorithmic bias, and armaments automation.

Specific taxation policies are most effectively applied to AI on a multi-jurisdictional basis, or by recognised supra- national organisations. The formulation and implementation of effective taxation policy agreements could take years and ultimately be ineffective when applied to a technology subject to huge velocity of change and development.

Any application of taxation policy specifically to AI is likely to be implemented on a jurisdictional basis in a post hoc manner in response to events, national or external which evidence the harmful effects of AI.

Why?

A number of situations would prompt such initiatives. Taxes on capital income would be applied to protect the tax base against a further decline in labour's share of income and to offset rising wealth inequality. That step requires both economic and political judgment by Governments against continually changing statistics and socio economic events. More likely taxation policies would be implemented following evidence of growth, high profile incidents and damage resulting from some of the possible harmful effects cited above. In effect such tax would be a “vice tax” similar to levies on alcohol, tobacco or gambling. A vice tax that could be varied according to the likelihood of AI inflicted damage. As such an AI tax would not be irrevocable: if it did not work as intended, the tax could be withdrawn without too much embarrassment.

When?

Timing is everything, as governments don’t plan tax changes much in advance. Normally they are imposed in response to political expediency and fortunes. Governments react to events rather than planning for them- increasingly so!

Precipitous tax changes focussed on a golden goose in the shape of AI can seem like a palliative for impoverished Governments. The right time if any to make such moves is as a process of reallocating wealth generated from the use of AI, to fund essential public services such as supporting elder care, social welfare and education- especially in the form of retraining.

These measures would address disparities, by ensuring that the benefits of the AI revolution are shared across the society. While these measures straddle discussions of legal, ethical, and economic impacts, all of which are critical for developing policies that are just and far sighted, the “future of work” remains at the core of AI deployment. Examining when and how AI is deployed, offers the opportunity to ensure that advances in AI strengthen, rather than undermine human welfare. Advocating an AI tax may be a pivotal step towards achieving a more equitable future for all.

How?

In summary, with difficulty. Technical transformation has been taking place in the world but the velocity of change only offers uncertainty about how things will shape in the future. In consequence the debate on taxation of AI and robots will still continue, as there is uncertainty whether high rates of unemployment will permeate society and its workplaces due to replacement of human workforce by machines.

Expansive and targeted proposals would be difficult to implement, as such proposals would counter commonly accepted principles of tax policy, such as neutrality, simplicity, certainty, efficiency, effectiveness, fairness, and flexibility.

The taxation of AI would slow down innovation across fields as diverse as science, health, economy, security, nutrition, the environment, and leisure. and so forth. Moreover, it would also deter people from enjoying innumerable benefits arising from AI in all those fields.

In conclusion from the perspective of peaceful and balanced Society, possibly the most concerning issue for the Governments of Western Societies today. Western Governments do have to be vigilant and proactive in managing the trends of unemployment and profound material and wealth disparity, as they can lead to civil disorder and even civil war. The institutions which have bound society together since World War II are stretched. AI is capable of weakening them further- that is probably the most disturbing aspect of the potential of AI.