Post Covid-19 Calcs - Has Financial Services Lost Purpose & Plot?

Friday, 01 May 2020By Paul Taffinder

Financial services may find 'post-covid-19' particularly painful. Although there was a slim window of opportunity, certainly missed, for financial services to lay out how, working with government, the sector could help people and businesses through the crisis. Instead, whatever opportunities existed were left to governments, and governments have largely been bypassing financial services (with perhaps the exception of a general reliance on payment services).

This may seem, at least to leaders in financial services sector, a perfectly legitimate response: it is the role of governments to handle pandemics. However, a goodly number of executives at the top of financial institutions must now be experiencing a rising sense of discomfort that somehow, at some point, in some way, their businesses have fallen short and perhaps have lost their fundamental purpose.

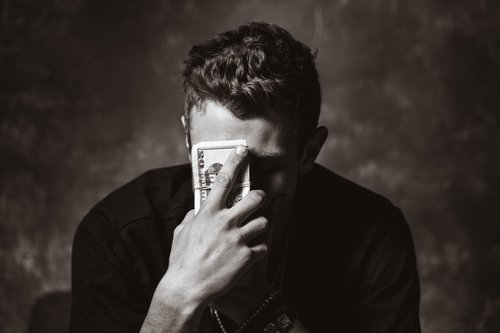

Purpose is terribly important to people in organizations. It is, after all, what gets employees out of bed in the morning, well, that and the money. Yes, making money helps, but what people, the world over and throughout history, want more than almost anything during times of upheaval, business disruption, technological churn or global pandemic, is leadership to guide them, offer context and therefore, meaning and purpose.

The present failure of financial services to step up and offer credit solutions that ease the disproportionate burden on medium and smaller businesses and, of course, the vast swathes of working people, may be due to a gradual erosion of purpose over two decades or more:

In the 1990s there was a new fashion in business to emphasize value-based management and total shareholder returns. In itself, this was a good discipline and rewarded many of the businesses (and executives) who pursued it with vigour: witness Sir Brian Pitman's leadership at Lloyd's Bank.

Value based management became the rage and, to a very large extent, the substitute purpose of financial services entities. We all know know where that led in 2007.

As my colleague, Professor Michael Mainelli notes, “During the financial crises in 2009, a BBC news team stopped a young banker on Finsbury Square and asked him to address Adair Turner’s rhetorical question, isn’t banking ‘socially useless’? The young fellow was flummoxed, shrugged his shoulders, and slunk away. How terrible is this – to go to work each day with no social purpose? I would hope that people in finance could explain to those outside why finance is socially useful – facilitating trade & commerce, providing social protection, promoting financial stability. Finance helps us make much better choices using society’s great decision-making mechanism, the monetary system. We have a boon with society. We’ve sold society a dream based on a theory, economics. To move towards that dream we have to work together building open and competitive financial services markets that price externalities.”

I contend that we should view financial services in the light of long, strategic mega-trends – not just the current crises (Covid-19) or more tactical obsessions (digitization and the threat of ‘digital’ competitors). Is it possible that there has been an over-focus for 25 years on shareholder returns? Has this become an orthodoxy in the wider sector, unchallenged and so ubiquitous that no one in the industry thinks beyond it? And has this unchallenged orthodoxy distorted the concept of credit and the actual role of the industry?

When you work in a particular context, and have grown up with the industry concepts, assumptions and indeed subconscious biases, it is often psychologically impossible to see that your institution is being carried on a wave whose dimensions and character have become inadequate or even damaging to customers and perhaps even society at large.

It is a failure at three levels: the financial services industry, the leadership and management of the institutions themselves and the decision-making of executives and responsible employees down the food chain. The distortion of purpose reinforces downward and upward. It is not a stretch to say that, in many an executive committee, deep discussions of customers, their current and future needs and the best ways to serve them are secondary (or often even lower in order) than financial performance, regulatory compliance (necessary, but reactive to legal enforcement), cost control and worries about how to make incremental improvements that keep you on a par with your competitors. If that is the nature of executive committee agendas, can it be denied that the same imperatives become the ‘legitimate’ decisions and actions of everyone else in the business? Leaders have followers and from time-to-time the leaders in an industry cannot see the wood for the trees – how is the typewriter industry faring these days?

After the 2007 financial crises, Long Finance proposed a ‘Long Banking’ project based around a small group of bankers seeking reform. In their own words:

“The Long Banking group propose to commission a project to show that bankers are interested in building a better society as a first step towards restoring credibility in financial services, particularly banking. The Long Banking group believe that the role of credit is core to all discussions about the role of banking. The proposal is to commission a project to produce a report entitled, ‘Credit Creation In The Modern Economy: A Discussion Of Leverage, Economy, And Society’. The project is much wider than a report. The process of conducting the research should be used to promote extensive engagement and discussion.”

The idea was to engage with society in a mature way about the social contract for banking, not just a PR/marketing effort on ‘rebuilding trust’, reminding us that bankers are humans and we all use financial services. Post-covid-19 society will be asking more questions about why, how, and where it needs credit, and why should it give the financial services sector a social mandate to provide it when governments appear to do all the work. Discussions about inequality will continue to rise in volume and importance and financial services industry should take responsibility for a proper discussion of the role of credit in a modern economy more seriously.

If that is the growing challenge at the industry level, there is nothing to stop leaders in individual institutions questioning the unconscious assumptions that operate so naturally (and legitimately) in regard to the purpose of their own organizations:

- Why are we in business?

- Whom do we serve and why should they come to us?

- How is our purpose (‘mission’) fit for purpose?

- Does our strategy align with our purpose?

- Do our executives and employees live our purpose?

Most of these questions apply equally at the industry or sector level.

Wouldn’t it be great if we who work in the financial services industry had developed considered answers to these questions and proposals for how to enact them? Wouldn’t it be great if we were ahead of the game when the painful critique of the industry’s social mandate and responsiveness to crises, both great and small, begins to bite?