Peak People: Finance and Fertility

Monday, 29 July 2024By Chris Yapp & Gillian Lockwood

Population is a topic that overlaps the interests of both of us. Gill has recently retired from a career in fertility medicine and has seen the development of treatment options flourish since the birth of Louise Brown, the world’s first IVF baby in 1978. Fertility medicine was once called Futility medicine, but not any longer. For individuals and couples around the world, the inability to have a child of their own can be personally and socially devastating but for states with demographic ambitions the consequences are incalculable .

At the same time, there are other voices who argue that the world population is too large to be sustainable. The result is that the problems are not to be seen solely through medical eyes, but also societal, economic and environmental. Too many babies, or where have all the babies gone?

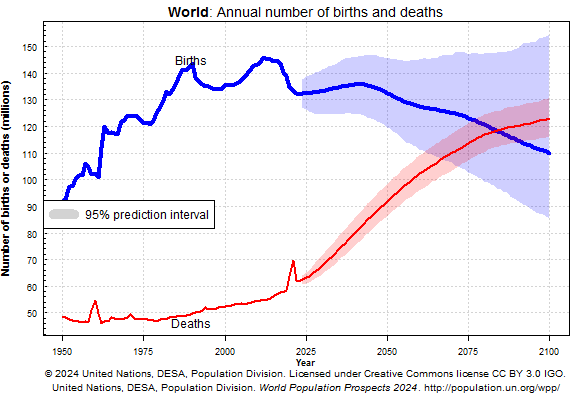

At the end of the last Millennium the consensus forecasts were that by 2100 the world population would reach around 15bn. By the start of this Millennium some argued that whatever action was taken then, the world population was on an inevitable path to 10bn. Would China or India be the first country to reach 2bn?

Over the last year, a different narrative has been developing. To maintain a stable population at the planetary level the fertility rate needs to be around 2.1 children per woman. Yet we now find that many countries are now well below that with the UK at 1.4 and South Korea at 1.1. In those countries, the ratio of the working age population to the dependent population ( children, the ‘economically inactive’ plus the elderly) is falling rapidly. The countries where the fertility rate is above 2.1 are largely in the Middle East, South America and especially Africa. Instead of China reaching 2bn, the consensus is that it will fall back below 1Bn. Despite lifting the 1 child policy, and now actively advocating two or three or more, Chinese women are simply not having more babies.

Also, with an increasing longevity, it is not absurd to think of a country in 2100 having more centenarians than under 5s.

There are some important underlying societal changes within these big picture statistics. The age of a woman’s first child has been increasing in the West for many years for women and in the UK it is currently 29. Where are all these ‘gym-slip’ mothers now?

In H G Wells’ “The Time Machine”, he envisaged a far distant world in the future where the human race had split into 2 distinct species with very different lives, the Eloi and the Morlocks. The Eloi were the ‘superior’ people who lived a life of decadent ease on the surface of the planet but were totally dependent on the subterranean, brutish Morlocks who would serve their masters but creep up to devour them when they could.

If he were alive today Wells would not find 2 species, but he might recognise a path evolving into two tribes.

Within the fertility statistics there are some very strong trends internationally.

Increasingly, family size is strongly negatively correlated with the level of a woman’s education. The more educated a woman is, the fewer children she has.

In many countries we have an emerging pattern of one group that has lower education, is resource poor, has larger families, poorer health and lower life expectancy ( the Morlocks). The other extreme is a group which is resource rich, has better health and life expectancy and smaller families( Eloi).

It is here that advances in medicine play a potential part. The technologies for 'fertility extension and preservation' have come a long way in the last 30 years.

Under military covenants some countries offer sperm freezing for young soldiers so that if military service impacts their fertility potential they can still become fathers. For women, egg freezing was initially developed to offer young women the opportunity to protect their future chance of genetic motherhood before undergoing cancer treatment that in the past would have ended their fertility potential. For many years now that scope has expanded in response to demographic changes to include 'social egg freezing'. Women’s fertility falls dramatically after the age of 37, while men’s does not. Many professional women want to establish themselves and their lives before starting a family. This is reflected in the number of companies who offer egg freezing as an employee benefit to help their more valued employees navigate their life choices.

Recent legislative changes in the UK which have extended the time-frame for ‘social’ egg freezing as an option for women, and significant technological developments (including vitrification and pre-implantation genetic analysis) have enhanced the ‘success rates’ for assisted conception, but the impact at the national level may continue to be small, albeit for the fortunate individuals , the impact is life-changing.

The above factors and trends have both direct and indirect impacts on the finance system. What happens to the pension industry if poorer communities cannot afford to retire or the wealthy don’t want to because they are enjoying good health? Also, what happens to wealth management if the rich don’t have families to leave their resources to?

One possibility is that more of the private sector globally could be 'owned' by foundations, such is the case of Rolex, which is owned by the Hans Wilsdorf Foundation. What would be the implications of that be for our financial systems?

One of the most helpful maxims in futures work is “a trend is your friend until it bends”. It’s useful to push trends out to extremes, not to support “we’re all doomed” messaging but to test when and how a trend may bend or indeed break.

If we take the current models forward, we can see some interesting areas of potential focus. To add to the challenge of “peak oil”, what are the implications of “peak people”?

At the extreme, consider the following examples:

- In what year would we need to sell more iPhoneXs than the world population?

- In which year would demographics lead to a decline in social media audiences?

- How will B2C eCommerce businesses adjust to fewer customers?

Now, the obvious comeback is “innovation”, which we would agree with. However, if the working population is supporting an increasing inactive proportion of the population, who will do the innovating?

Let us turn attention now to the countries where fertility rates are still above 2.1, such as Niger at 6.3 or Uganda at 5.2. Here there is another trend that needs unpicking.. Thanks to the work of UNICEF and the WHO, among others, child mortality is falling globally. So, a family 1 or 2 generations ago might have had 8-10 children, and 4 reaching adulthood would have been a good outcome. Now they might have 6 children but 5 survive. Go forward another generation and we see family sizes falling towards European and US rates.

So we find countries with an excess of working age adults for the economies around them. This is a significant contributory factor in increasing economic migration from Africa to Europe, for instance. We are seeing the political consequences of that in many countries. Graduates with useful degrees literally fight for employment opportunities in countries that lack the resources and infrastructure to take advantage of their talents. The countries that are most in need of working age people are increasingly resistant to immigration. At the same time, we find populists arguing that women need to have more children, notably in the US, Japan and Europe.

Yet a survey of social action around the world is not encouraging. Even in Scandinavia, with high levels of social provision for parenting leave and child care, the trend of decreasing fertility is as pronounced as countries with weaker provision. Economic incentives do not appear to work. Governments have tried bribing and bullying women to have more children (or even any children!) but they just won’t.

So where do you invest to maintain innovative capacity against population collapse?

Some suggestions might be in Higher Education and Infrastructure in those countries with higher fertility rates. The latter is clearly where China is investing. What are the western financial hubs doing or need to do? There are no easy answers.

Gill’s recent book, “Egg Freezing in the 21st Century: a Global Perspective” starts from a medical practitioners view but explores the societal and economic challenges within which medicine is developing. It’s been fun for both of us to see it come together.