ESG Integration - A Demonstration Of Its Effectiveness And Resistance To Its Adoption

Tuesday, 17 June 2014By Robert Schwarz

Abstract: The use of the Sustainable and Responsible Investing strategy of ESG Integration (ESGI) is well established; empirical data supports its success in achieving superior risk-adjusted returns over the long-term, there is notable use of it among investment managers, an industry to support its use, and demand among investors for it. Many investment managers, however, have not implemented ESGI and attempts by ESGI’s advocates to inform them of its benefits have seen limited success. Using sociological theory as a guide, this article provides an explanation for the limited success of these attempts by suggesting that acceptance of the effectiveness of ESGI represents a threat to an investment manager’s identity. The article goes on to offer proposals for how to circumvent this challenge to getting investment managers to implement ESGI by appealing to their competitive nature.

An edited version of this article was published in CISI' Review of Financial Markets, June 2014 edition.

Introduction

One who instinctively or habitually doubts, questions, or disagrees with assertions or generally accepted conclusions, is known as a skeptic[1]. Being one myself, I understand and appreciate this instinct, and over the years it has served me well in many situations and I expect it will continue to do so. Therefore, I also respect this approach. When it comes to the Sustainable and Responsible Investing (SRI) strategy of ESG Integration (ESGI), this mindset is warranted.

Although there is a considerable amount of empirical evidence that demonstrates the achievement of superior risk- adjusted returns over the long-term through the use of ESGI, there are challenges associated with its implementation. Given the evidence in favor of ESGI and the persistence of the efforts of its advocates, however, one would expect a greater degree of adoption. The author believes that part of the reason for the low level of adoption is the approach used by its advocates to overcome Investment Managers’ (IM) skepticism. In search of a reason(s) for this disconnect, answers where sought in socio- behavioral theory. The answers found provide information useful to better understanding resistance to ESGI as well as in enabling advocates of SRI to formulate a more effective approach to getting IMs to integrate ESG criteria into their investment decision-making processes.

In this article, environmental, social, and governance (ESG) and ESG Integration (ESGI) are defined and evidence supporting the benefits of both presented. Next, an overview of typical arguments made against this investing strategy by skeptics is presented. Responses from a hypothetical advocate of this strategy, which one would expect to convert ESGI skeptics, accompany these arguments. The article proceeds with a brief discussion of the approach that has been used to argue in favor of ESGI and why the strategy employed has seen limited success. From there, an exploration of socio-behavioral motivators and thought processes provides a deeper understanding of IMs’ resistance to ESGI. Finally, based on the reasoning offered, suggestions for a new approach to getting IMs to implement ESGI by appealing to their competitive nature are provided.

Definition of ESG

For the purposes of this article, environmental, social, and governance (ESG) refers to the consideration of how these factors affect and are affected by the operation of a business entity. The proper management of ESG performance involves the consideration of these factors at the operational level and within a company’s overall business strategy. The actions needed to accomplish such an organizational synchronization require a sophisticated and nuanced understanding of the operational, financial, regulatory, and reputational risks related to global environmental, social, and economic issues that affect the viability of a business. On top of this understanding, a substantial commitment of organizational resources, courage, and conviction is required from corporate leadership and management in order to envision, devise, plan, and execute the paradigm shift away from a “business as usual” mindset in order to institutionalize these considerations into all management processes.

These resources and efforts, in turn, enable the identification of opportunities that arise from the aforementioned risks. Such opportunities include improving upon environmental and social outcomes of operations and the optimization of corporate decision-making capacity through the implementation of technologies, programs, and behavioral incentives. Environmental improvements include CO2e emissions[2] and water use reductions and improved waste diversion rates. Societal improvements include holding suppliers to internationally recognized environmental, health, and safety standards as well as the development of products and services that address the needs of underserved markets. Opportunities to optimize corporate decision-making capacity include the implementation of governance policies[3], that link executive pay to long-term company performance, ensure executive boards are independent and reasonably diverse in terms of race and sex, and engender the prudent identification and selection of executives and directors. Finally, the communication of these efforts and the associated successes and challenges to share- and stakeholders as well as the public through appropriate reports and disclosures is essential to realizing the full compliment of associated benefits.

As one can see, ranging from energy efficiency to board oversight, a defining characteristic of ESG opportunities is their breadth and interdisciplinary nature. This nature requires management excellence across a broad range of skills and experience and highlights the need for well-qualified and capable leaders, managers, and staff. As such, there is a widely accepted notion that the active management of a company’s ESG performance is a strong indicator of a generally well-managed operation. From this maxim arises the premise that companies that have programs in place to identify and manage ESG-related risks and opportunities are better positioned to outperform their peers across the value chain.

So as not to create the misperception that ESG performance management is a potential means for all companies to outperform the market, however, let it be understood that implementing the principles and practices of sustainability only makes sense for companies offering a viable product(s) and/or service(s). This being the case, there is no doubt that in addition to determining leaders and laggards, the successful management of ESG will crown winners and force the exit of losers. Such outcomes are not to be lamented though as they are a beneficial outcome of equitableii competition in market-based economies.

Noting the caveat above, the resources that must be invested and the organizational change required to successfully institutionalize sustainability does bring rewards. These rewards come in quantifiable formsiii such as increased operating and profit margins; improved access to capital; stronger brand reputation, enhanced employee satisfaction, and workforce and community development. These benefits drive overall, long-term outperformance of the market, thus demonstrate the value inherent in managing ESG performance. Case-study[4] evidence substantiating this claim to the tune of billions of US dollars using the Value Driver Model[5] can be found at the United Nations Global Compact website.

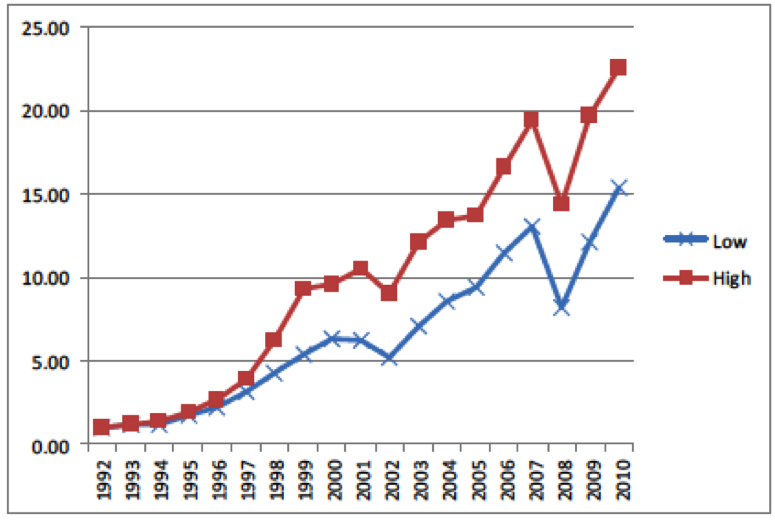

A more immediate example, that substantiates the positive correlation between active ESG management and superior overall management and that demonstrates how ESG performance management can affect stock price is provided by results of the Harvard Business School study[6] shown in Graph I. The study compared the stock performance of a portfolio of firms that successfully manage ESG with a portfolio of firms that do not manage ESG over the same 19-year time period. The red line shows that US $1 invested in a portfolio of firms that manage ESG would have grown to US $22.60, whereas US $1 invested in a portfolio of firms that do not manage ESG would have only grown to $15.40.

Graph I: The affect of ESG performance management on share price

Source: Eccles, Ioannou and Serafeim (2011)[7]

Definition and Use of ESG Integration

ESG Integration is a Sustainable and Responsible Investing strategy that involves determining sector-specific, material, quantitative and qualitative ESG key performance indicators (KPIs) associated with the results of managing ESG performance then incorporating them into traditional financial analysis. The objective of ESGI is to generate long-term, risk-adjusted financial returns that outperform the market through the integration of ESG criteria into investment decision-making processes throughout the investment cycle.

Financial analysis that incorporates the use of these KPIs helps investment managers identify market leaders and laggards in terms of their ability to capitalize on risk-reduction and efficiency-enhancing opportunities associated with their management. These determinations are possible because the disclosure and reporting of ESG performance by companies provides IMs with the opportunity to ascertain more comprehensive operational-level information about a company, thus the possibility to gain insights across the value chain. Furthermore, as ESGI considers factors that fundamentally affect a company’s ability to create economic value, integrating ESG KPIs with traditional financial analysis enables IMs to better assess operational, financial, regulatory, and reputational risks and opportunities. In turn, enabling them to build more informed risk profiles and financial models with greater explanatory and predictive power than conventionally built models, thus producing a more comprehensive assessment of an investment than financial analysis alone is capable, thereby enabling better evaluations of an investment’s potential to outperform the market[8] over the long term.

ESG KPIs can also be used to:

- Determine and monitor companies’ ability to adapt to changing market conditions;

- Quantify managerial performance beyond financial measures;

- Enable more accurate industry peer comparisons;

- Mitigate and take advantage of, respectively, newly identified ESG-related risks and opportunities, and

- Keep track of ESG-related incidents that may adversely effect a company’s brand and value.

Evidence of ESGI’s Effectiveness

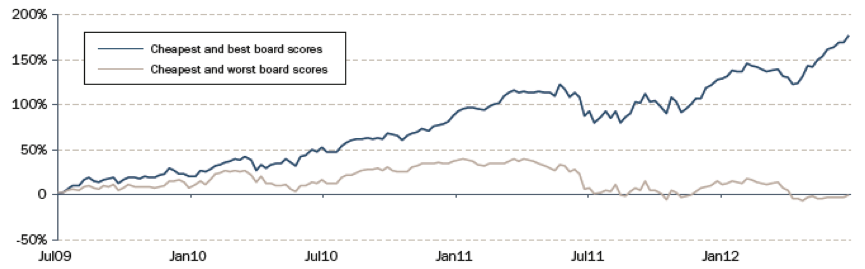

The theoretical benefits of ESGI are born out in its practice. An example provided by AXA Investment Managers[9], which illustrates the identification and integration of ESG KPIs into financial analysis is provided in Graph II:

Graph II: The affect of board score on share price

Graph II illustrates that the share price of the companies with the best board scoresiv outperform companies with the worst board scores, i.e. those with the best board scores returned 40% on an annualized basis, whereas those with the worst board scores returned -0.3%. Although this may not seem all that insightful as one would expect poor leadership to result in poor company performance and vice versa, the fact is that analyses such as these are not undertaken outside of firms that have adopted ESGI. The potential negative consequences of not doing so are missed investment risks and opportunities that can affect portfolio value as exhibited in the above example. Despite this evidence, which supports the relevance and value of ESGI, approximately only 10% of global assets under management (AuM) employ an ESGI strategy. Considering that examples such as these abound across the spectrum of ESG KPIs and the potential implications the results hold on portfolio performance, one is justified in questioning why more investment managers have not adopted ESGI; answers to this query are laid out over the following two sections.

The Skeptics’ Position and a Hypothetical ESGI Advocate’s Response

Typical challenges made by those who have been exposed to the existence and benefits of ESGI have their origins in a lack of understanding of what ESGI is, and question the veracity and indeed existence of data that establishes its effectiveness. Without trying to exhaust all of the challenges, the following six ESGI skeptic positions (SP) and ESGI advocate responses (AR) are offered as representative of the arguments from both sides:

- SP: There are no or very few long-term studies that verify ESGI’s effectiveness; data is sparse and inconsistent.

AR: In addition to this objection being misplaced, i.e. there are plenty of examples of the wide-spread use of unproven investment strategies[10], e.g. collateralized debt obligations, it is also simply untrue. Instead of citing multiple studies that verify the effectiveness of ESGI, however, two study-of-studies are offered, which achieve the same purpose through an examination of multiple academic and investment management firm conducted studies.

The first study, “Demystifying Responsible Investment Performance: A review of key academic and broker research on ESG factors”[11], was conducted by The Asset Management Working Group of the United Nations Environment Program Finance Initiative and Mercer. Of the five studies it reviewed that employed a pure ESGI strategy, 80% had a positive correlation with outperformance of the market.

The second study, “Sustainable Investing: Establishing Long-Term Value and Performance”[12], was conducted by Deutsche Bank Group’s Climate Change Advisors . Two key findings of their review of 100 academic studies of sustainable investing around the world, 56 research papers, two literature reviews, and four meta studies were:

1) “89% of the studies examined show that companies with high ratings for ESG factors exhibit market-based outperformance,” and

2) “100% of the academic studies agree that companies with high ratings for Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and ESG factors have a lower cost of capital in terms of debt (loans and bonds) and equity.”

Further evidence of the effectiveness of ESGI is offered through the multitude of well-known and respected investment managers, which collectively represent hundreds of billions of AuM, that have implemented ESGI in the operation of their Mutual Funds and other financial products, e.g. Calvert Investments, Parnassus Investments, HERMES, Deutsch Bank, Breckinridge Capital Advisors, etc. Similarly, major pension funds and endowments, which also represent hundreds of billions in AuM, have implemented ESGI, such as Harvard Management Company, Ontario Teachers Pension Plan (OTTP), APG, PGGM, HESTA, and CalPERS, to cite just a handful. Private Equity firms have also begun integrating ESG criteria into investment decisions. Some notable firms include TPG Capital Advisors, LLC, Apollo Global Management, LLC, The Blackstone Group, and The Carlyle Group.

Regarding issues with ESG data, there are challenges regarding data availability, consistency, reliability, and verifiability. These issues are mainly related to the nature in which companies report ESG data, the frequency they do so, and legal concerns regarding data sensitivity. In some cases, these issues render the data difficult to work with in general and for the inexperienced can lead to the misidentification of leaders as laggards and vice versavii. Similarly, a standard framework and methodology for scoring companies based on ESG performance is absent, which can lead to misconceptions regarding which ESG KPIs are material and which are not, the latter being irrelevant[13] to ESGI.

Although the scoring issue remains, within the last few years the data issues have vastly improved. In fact, there is an industry dedicated to providing quality ESG data precisely to enable ESGI and other SRI strategies. Providers of ESG data include Sustainalytics, TRUCOST, Asset4, MSCI, CSRHUB, Bloomberg ESG, GMI, RepRisk, and FACTSET. ESG data can also be obtained during analyst calls, and other means of direct communication with companies provided one knows the types of questions to ask.

In addition to these resources, there is an abundance of thought leadership, networking opportunities, information services, and other types of support available through organizations that exist to advance SRI, e.g. United Nations-supported Principals for Responsible Investment (UN PRI), European Sustainable Investment Forum (EuroSIF), US Forum for Sustainable and Responsible Investment (US SIF), and many others. - SP: Integrating ESG metrics into investment decision-making contravenes my fiduciary responsibility.

AR: It is true that some SRI strategies subordinate financial returns to positive social and environmental impactx and/or actively eliminate industries from a potential investment universe. An example of the latter is Screening, which excludes industries based ethical and moral standards. The conventional set of so-called “sin stocks,” which are screened include companies directly or indirectly involved in any way with pornography, tobacco, firearms, alcohol, or gambling. While many investors wholeheartedly object to such strategies as they view such restrictions as necessarily limiting potential returns, ESG Integration, is not restricted in this manner as there is no predetermined proscription of one’s investment universe as indicated in the previous section, Definition and Use of ESG Integration. To be clear, using an ESGI strategy a company like InBev (a sin stock) could be included in an investment portfolio provided it scored well on an ESG assessment.

With this differentiation clarified and the definition of ESGI in mind, it is plain to see how ESGI enhances an IM’s ability to assess potential return on investment (ROI) by providing a more comprehensive evaluation of a security. Thereby improving fiduciaries’ ability to act in the best financial interest of their principal; a position also held by United States Department of Labor[14]. - SP: ESG is a compliance issue, why bother if companies are required to manage these aspects of their operation?

AR: Many companies are out of regulatory compliance and generating above-average returns. From an ESGI perspective, however, such a scenario may indicate, e.g. deeper environmental, health, and safety (EHS) issues, which would be perceived as a risk signal to be analyzed using ESG KPIs that have been shown to be reliable indicators of poorly performing management, e.g. number of employee accidents/barrels of oil produced. A consistently poor rating on this ratio could be a sign that management is cutting corners on EHS to increase profits. If these issues are not addressed, an ESG Analyst would surmise, they could contribute to a reduction in the value of a security over time. Another scenario, illustrated by British Petroleum’s (BP) Deepwater Horizon debacle, is when these issues cause a catastrophic event that decimates a stock’s value. When these types of metrics are meaningfully integrated into financial analysis as previously described, however, they can significantly reduce, if not eliminate, the occurrence of such portfolio devaluation scenarios.

Finally, compliance is about meeting a minimum standard. Highly successful businesses go far beyond this measure. Managing ESG performance is about creating economic value through product and service improvements and innovations and using inputs and producing outputs more efficiently to increase financial performance, strengthen brands, satisfy customers and clients, improve employee satisfaction, and grow communities. Companies that can achieve this type of operational excellence are better poised to outperform the market over the long-term. - SP: Show me how to achieve alpha using ESGI. The sub-text being, if I can’t get alpha using ESGI, I am not interested.

AR: There are investment managers who are achieving alpha using ESGI. Andre Bertolotti, Chief Investment Officer at Quotient Investors is one. He has outperformed the Russell 1,000[15] by 4.88 percentage points over the last three years. Extolling the effectiveness of ESGI he flatly states, “Without ESG, my portfolio would look like that of many other managers... But when you bring ESG into the picture, I end up buying a different set of stocks”[16].

A similar example demonstrates how ESGI enables investment managers to avoid losses. Through its use of ESGI, Domini Social Investments, which manages mutual funds with a combined AuM of US $1.3 billion, became aware of the type of regulatory and worker safety compliance issues at BP that were eventually recognized as the cause of the failure of the Deep Water Horizon oil rig. Based on its ESG analysis and rating, BP shares were not purchased. - SP: There is very little or no demand from investors to consider ESG criteria into investment choices, their only concern is financial returns.

AR: Regarding current demand for ESGI, US SIF reports[17] that client demand is the top reason investment managers are adopting ESGI. What is on the demand horizon, however, is perhaps more important though. In seeking to answer this question, one would discover four key facts:

1) An estimated US $41 trillion wealth-transfer is expected to occur from Baby Boomers to Generations X and Y (GX&Y) over the next 40 years[18].

2) 36% of respondents to a World Economic Forum (WEF) study[19] of 5,000 Millennials, aka Generation Y, across 18 countries ranked ‘to improve society’ as the primary purpose of business.

3) GX&Y value price over brand, are not known for brand loyalty, and are not averse to switching costs[20].

4) GX&Y’s use of the internet to inform themselves and to take part in their chosen causes differs markedly from that of Baby Boomers[21].

Given these findings, it is reasonable to conclude that, “the emerging generation of investors is likely to seek achievement of social objectives in addition to financial returns”[22]. It is equally reasonable to conclude that in order for IMs to be able to take advantage of the expected wealth-transfer opportunity, they will need to accommodate the differences between the investor profiles of GX&Y and Baby Boomers (whose assets they manage now)[23], by rethinking their investment strategy to include ESGI. - SP: Implementing ESGI is resource intensive and we are doing fine. ESGI is not worth the effort needed to implement the entirely new set of skills and procedures that are required. For example, consultants may need to be brought in, staff will have to undergo extensive training and/or new staff may need to be hired. Likewise, depending on the degree to which ESGI is implemented, the following types of changes, potentially among others, may need to be planned and executed:

1) Organizational structure adjustments;

2) Data acquisition and integration;

3) Development of website and other marketing material; and

4) Workflow re-engineering. Moreover, from a Human Resources perspective, these types of changes require executive level support and a culture and level of employee engagement that is able to cope with the disruptions and natural resistance to change involved.

Without these success factors in place, declines in morale and productivity are likely.

AR: All of these actions may indeed be required and ESGI does require an upfront and ongoing investment of human and financial capital. However, the crux of the matter is whether or not the benefits of implementing ESGI outweigh the costs of doing so.

Regarding this question, it is not necessary to institutionalize ESGI from the outset. An IM could initiate a pilot project employing ESGI as a means to determine the viability of the strategy. The results could then be compared with traditionally managed assets and a decision made as to whether or not to proceed further. Keeping in mind of course, the US $14.76 trillion pool of capital that may require the demonstration of an implemented ESGI strategy and empirical evidence that demonstrates its effectiveness.

Additional facts to consider in this decision include that IMs successfully using ESGI are competitors with an advantage. One may further consider that despite large-scale resistance there is a trend towards the use of ESGI among IMs being partially driven by the burgeoning demand among retail investors previously cited, i.e. UN PRI signatories have grown to 1,248 members, representing US $34 trillion in AuM[24], in the last eight years. There is also a host of ESG-related disclosure, reporting, and public listing practices and policies on the horizon that may affect companies’ financial performance, which will need to be monitored by IMs.

As these initiatives are in their early stages, having an ESGI program in place is still a means to differentiatexii one’s firm from competitors, thus a potential source of competitive advantage. If realized, these two factors can serve to enable the supply of emerging demand for SRI products and the demonstration of regulatory compliance, which amounts to increased potential, relative to competitors, to realize positive ROI through acquiring new clients that may not have otherwise invested with the firm and attracting additional capital from existing clients.

Explaining Resistance to ESGI and its Potential Consequences

Although the challenges are reasonable, one would expect the responses, which amply address the criticisms andconcerns embedded in the questions, if communicated effectively and in accordance with one’s audience, to clear up skeptics’ misunderstandings and properly reset their expectations, thus convert skeptics. Moreover, if ignorance and/or limited cognition were the cause(s) of ESGI skepticism, one would expect that some further education in line with the previous responses would be sufficient to convert skeptics. Given the steadfast persistence of the attempts to overcome ESGI resistance, however, this does not seem to be the case.

A clear factor contributing to ESGI skepticism is the fear-mongering, plays at sympathy, and information overload typically included in ESGI advocates’ attempts to convert skeptics. Which is not to claim that the assertions made regarding, e.g. habitat loss, sea-level rise, the health effects of pollution, etc. are not true and relevant, rather, that they are not effective towards inducing behavior change among IMs for which these negative consequences have no immediate bearing or import. Also included in ESGI advocate’s strategy to relay its benefits are the use of terms such as sustainable, responsible, environmental, ethical, etc., which for many IMs carry negative connotations[25]. The logical thinking behind including these components in their strategy is that if the information and implications are properly explained and the data and methodology verified and substantiated, it will be accepted by IMs and ESGI implemented accordingly.

Ostensibly, the combination of the previously described challenges and strategy are the basic reasons behind IMs’ resistance to implementing ESGI, and they have typically led to its dismissal as a viable investment strategy. Given the steadfast persistence of the attempts to overcome this resistance, however, the author believes that an explanation is needed that provides a more complete account of ESGI resistance among IMs vis a vis its empirically based benefits and the existing and future demand for its use.

In recognition of this need, the author called upon sociological theory for insights into the possibility that there are deeper motivations and thought processes driving resistance to ESGI. The following five examples offer just that:

- Cultural Cognition theory posits that as scientific knowledge and numeracy increases, i.e. the “smarter” one is, among those with a worldview that, “ties authority to conspicuous social rankings and eschews collective interference with the decisions of individuals possessing such authority,” i.e. the more one espouses the benefits of a hierarchical social order, the more likely one is to question the data and information with which they are presented[26]. As IMs generally fall into this character category, it is reasonable to expect them to instinctively doubt the benefits of ESGI.

- Motivated Avoidance theory posits that when faced with a complicated, complex, and troubling issue, some individuals’ instinct is to give up and not learn more about it, i.e. they do not endeavor to come to an informed conclusion based on non-biased information[27]. Thus, their skepticism arises from their lack of knowledge being ‘informed’ by the disagreement surrounding the issue and any potentially conflicting information they are exposed to in their everyday life, such as, respectively, opposing positions in one’s firm regarding the pros and cons of ESGI and the views expressed by conservative news outlets regarding the risks of Climate Change, resource scarcity, etc. With the risks of ESG thus in doubt, the relevance of ESGI is questioned.

- Some hold that there is money being made in the form of grants, subsidies, and donations by climate scientists, governments, and not for profit entities that accept the reality of the ESG issues facing society as a result of business operations[28]. Therefore, being financially motivated, their “alarmist” claims, are specious. Again, with the risks of ESG in doubt, ESGI’s relevance is questioned.

- Under the heading of fear, when some individuals are presented with threatening information their instinct is to deny the truth of the information and/or its applicability to them. Similarly, humans are notorious - among economists - for underestimating the risks associated with likely events and overestimating the risks of unlikely events[29]. Thus, in both cases, the threat of imminent danger is denied. The danger in this case being that resistance to ESGI is unfounded.

- Building upon the sociological concepts of confirmation bias, wherein one “give[s] greater heed to evidence and arguments that bolster [their] beliefs” and disconfirmation bias, wherein one “expend[s] disproportionate energy trying to debunk or refute views and arguments [they] find uncongenial,” is the rationalization explanation. That is, when presented with information that questions deeply held beliefs and/or that one’s way of life could be fundamentally threatening to society, they reject the validity of the source of the information[30]. Thus, the information itself cannot be correct. As IMs generally fall into the category of being “well-off,” it is reasonable to expect them to instinctively defend the means by which they achieve their socio-economic status.

These five explanations provide useful information regarding underling subconscious biases that add to the previously stated challenges associated with implementing ESGI and help to better explain why attempts to overcome resistance to ESGI have seen limited success. To wit, they reveal that accepting ESGI’s effectiveness may represent a threat to an IM’s basic human instinct of identity preservation.

An aspect of identity being preserved, through denial, is an IM’s level of intelligence and self-worth as manifested in career performance. That is, if an IM admits that ESGI is an effective investing strategy they will also conclude that their returns could have been greater. Such an admission, after years of claiming to have been doing the best for their employer, clients, etc., could be very uncomfortable and possibly embarrassing. Mental health professionals refer to this type of internal conflict as cognitive dissonance, i.e. the discomfort felt as a result of attempts to simultaneously maintain two conflicting cognitions. In this case, “I have done my best” and “I dismissed, without sufficient reason, information that would have improved my performance.” This discomfort often leads to decision-making that serves to moderate emotions that fuel anxiety. Denial of the effectiveness of ESGI would avoid the anxiety associated with accepting its effectiveness, thus preserve one’s sense of career accomplishment.

Another aspect of identity being preserved is an IM’s self-image as a “good person.” That is, admitting ESGI’s effectiveness will force an IM to realize that businesses that do not manage ESG performance are significantly contributing to the environmental and social issues facing society. With this realization may come another, i.e. as a consequence of not adopting ESGI, they may have made an outsized contribution to these issues. As such, they may have, albeit unwittingly, further jeopardized the health and future wellbeing of their family members, friends, themselves, and indeed the rest of the world, a notion certainly capable of inducing a fair bit of anxiety. Analogous to the previous example then, denial of the effectiveness of ESGI would preserve one’s self-image as a “good person.”

Suggestions for a New Approach

The combination of obstacles stated in the previous sections severely diminishes if not eliminates the power of an attempt to appeal to skeptics’ sense of logic and reason with a sensible argument backed up by empirical evidence. That is, providing text and data-laden pre- and proscriptions for IMs to follow, as has been employed by ESGI advocates to date, has not proven to be an effective strategy. This being the case, a new approach is called for. As such, in an attempt to circumvent the threat posed to skeptics’ identity, their distaste for terms and concepts commonly used in the context of ESGI, and the disregard for the environmental and social benefits ESGI can effect, the following suggestions for ways to increase the adoption of ESGI are offered. They seek to appeal to the competitive nature of IMs to the exclusion of trying to raise awareness and increase understanding of the implicit environmental and social benefits of ESGI:

- Similar to the XPrize[31], a competition could be issued to achieve alpha through the use of ESGI. Similarly, more prizes like the Moskowitz Prize for SRI[32] could be made available to students.

- ESGI coursework could be added to the curriculum of business classes and more ESG-focused extra-curricular opportunities such as the PRI Young Scholars Finance Academy[33] could be offered. Similarly, more ESGI training, such as that provided by Responsible Investment Academy[34] and the Robert F. Kennedy Center for Justice and Human Rights Compass Sustainable Investing program[35] could be made available.

- An SRI professional accreditation could be formed, possibly as a sub-designation to a Certified Financial Analyst (CFA). In fact, this possibility was recently reportedxvi on by The Guardian[36] and was a topic of discussion at a recent meeting of the Vancouver CFA Society[37].

- Mainstream, finance finance-focused media outlets, such as Morningstar and CNBC could dedicate coverage to IM’s’ that are generating alpha using ESGI.

- A publically available directory of SRI managed investment products could be built to inform and drive retail investor demand

- Investment Management firms could align compensation structures and performance appraisals with the use of ESGI.

- Eligibility for banking and investment subsidies could be restricted to firms that have a predetermined minimum percentage of their AuM using ESGI.

- Standard reports issued by indices and exchanges could be benchmarked against a comparable index of assets determined as sustainably managed, for example, MSCI ESG World and Dow Jones Sustainability World then distributed through social media applications and financial news outlets.

This suggestion is supported by studies, which have shown that one of the most effective methods to induce behavior change is to regularly deliver messaging that employs easily understandable, ‘every day’ language and graphics to convey a gentle command that also relates a benefit into a single ‘takeaway’ or lesson. Essential to the effective consumption of the message is the full consideration of one’s audience in terms of the language employed, the incentive described, the delivery method, and who or what is delivering the message. Finally, it is noteworthy that some degree of trial and error may be necessary to realize the maximum potential behavioral change through this method.

As it happens, the most powerful among the four benefits proven to be the most motivational is financial, the other three are, in order of relative power, health, environmental, and social cachexviii. Using this insight, the previously mentioned factors and others could easily be incorporated into basic comparisons using tables and/or charts configured in such as way as to raise awareness among investment managers of the effectiveness of ESGI in generating superior risk adjusted returns. The takeaway being something in keeping with the notions of increasing clients’ returns, earning a larger bonus, attracting more capital, etc. Regarding the latter, for messages delivered in the digital realm, functionality could be included in the message to, “connect with investors now!”

Advantages of the above suggestions include being consistent with investment managers’ desire to outperform the market and their competitors, relatively easy and inexpensive to implement, and save for suggestion 5, not fraught with political and regulatory barriers that must be overcome in order to be implemented.

Conclusion

This article has explained what ESG and ESGI are and presented empirically based evidence for advantages of both. It has also presented the challenges associated with implementing the latter and described why the efforts of its advocates to get IMs to implement ESGI have seen limited success. Although a course of action that enables IMs to capitalize on the opportunities than can result from implementing ESGI comes with an initial expense of time and resources, these costs can, with proper planning and execution yield positive ROI through the aforementioned benefits of ESGI. As such, there is a strong case for adopting ESGI as doing so is in the best interest of the long-term success of an IM. Towards this end, with the aid of sociological theory, suggestions have been offered to help induce IMs to implement ESGI, thereby increase the percentage of global AuM employing ESGI.

Continued resistance to ESGI serves to exacerbate past and perpetuate continuing “business as usual” corporate behaviors that are a significant cause of negative environmental, economic, and social outcomes. So not only is the failure to adopt ESGI potentially detrimental to portfolio value, continued investment in companies that do not manage environmental, social, and governance performance is a positive reinforcement to bad corporate behavior.

Given the environmental, social, and economic challenges facing society, it is the author’s hope that this article will induce IMs to (re)consider implementing ESGI, the suggestions be acted upon, and that further use of the sociological insights provided will be made by ESGI advocates in their efforts to get IMs to implement ESGI.