Contagion: The Destructive Force Of Bank Credit

Thursday, 16 April 2020By Alasdair Macleod

Commentators routinely confuse the deflationary effects of a contraction of bank credit with the inflationary effects of central bank policies designed to offset it. Central banks always ensure their stimulus is greater, so inflation, not deflation, is always the outcome.

In order to understand bank credit, we must enter the mind of a banker and understand how it is created, why it is expanded and why expansion is always followed by a sharp contraction.

We have moved on from a simplistic credit cycle model. The global economy was facing a tendency for bank credit to contract even before the coronavirus drove supply chains into the greatest global payment crisis in history.

The problem is now so large that, to maintain both economic stability and price levels for financial assets, central banks, led by the Fed, will have to issue so much base currency that fiat currencies will become almost worthless.

In these conditions the banks that survive the next few months will then begin to expand bank credit anew to buy up physical assets, instead of their normal financial fare, sealing the fate of fiat currencies with a final expansion of bank credit as the banks themselves dump worthless currencies for real assets.

Introduction

At a time when governments and central banks are relying on commercial banks to transmit Keynesian stimuli to distressed borrowers, it is vital to understand the psychology and motivation behind changes in the level of bank credit. Furthermore, it has never has it been more important for analysts to differentiate between deflationary forces that come entirely from the contraction of bank credit, and inflationary forces that arise from central banks’ monetary policy.

Whether policies to rescue economies from the financial and economic effects of the coronavirus will actually get to the intended businesses, depends largely on the transmission mechanisms for base money. While special powers for the direct funding of large corporations may be implemented and the extension of public ownership to prevent bankruptcies of large players is very likely, commercial banks will be expected to play a central role in distributing monetary stimuli to businesses of all sizes. However, as they regard small and medium size businesses as either too risky or not worth bothering with, it is going to be a struggle to get them to deliver the financial support required.[i]

In any advanced economy, a Pareto 80% of GDP is provided by small and medium-size enterprises. In a highly centralised banking system, for banks that have access to the Fed through prime broker subsidiaries, SMEs are simply not worth bothering with. It leaves the majority of enterprises providing goods and services to the public out in the cold. Bankers looking through the dip will want to preserve more profitable relationships with large corporations and reduce their exposure to risky, expensive-to-administer smaller loans.

Despite the central banks’ generous intentions, the majority of businesses that rely on bank lending for working capital will therefore find finance frozen by bankers now driven by fear of risk instead of grasping lending opportunities underwritten by government support. Businesses with cash will learn that they are taxed by the debauchment of their money to subsidise failing competitors.

Investors who are used to getting positive returns solely on the back of expansionary monetary policies are now egging on the authorities to spend, spend, spend one more time. Penson funds and insurance companies in particular will now discover they are being lumbered with the cost of monetary expansion by an increasing depreciation of the currency, which escalates future liabilities. Ever since the investment industry pandered to the inflationary policies of central banks this outcome was inevitable, because both logic and sound economic theory tell us that you cannot continually inflate your way out of trouble.

That end point is where we have now arrived. The state has come to rely completely on inflationary stimulation. The helicopters have warmed up and are ready to distribute the monetary largess created by the magic of central banking, not just to individuals, but to their employers as well.

Mission impossible is to restore economic activity to where it was before the coronavirus shutdown. Politicians assume this can be achieved by deploying military precision. They have taken for themselves a mandate to sweep aside all bureaucracy and all objections to the role of the state. All it requires is for the banks as well as other critical actors to submit to their authority.

The Credit Cycle Was Turning Down Before The Virus Hit

The credit cycle was already turning down in the second half of last year. In response, the Fed first stalled its attempt to restore its balance sheet to normality and from September onwards was forced to publicly intervene to inject massive amounts of liquidity into the banking system through the repo market.

All was not well in wholesale dollar markets at least five months before the virus hit, so the problem is more complex than a simple return to normality when the virus passes. Furthermore, the authorities trying to keep the economy from imploding are out of their depth, so much so that individuals in the private sector are gradually realising it as well. Financial risk has escalated considerably, which has one effect: bankers will use every opportunity to reduce the size of their balance sheets. The authorities will struggle to get banks to hold fast, let alone distribute subsidies to producers and consumers alike.

Attempts at rescuing the global economy and supporting financial asset values upon which bank collateral is based will require massive inflation of base money, as outlined later in this article. But these attempts will have to fight bankers trying to control their lending risk in order to protect their shareholders’ capital from being wiped out. Their motivation to deflate bank credit will be greater than ever before.

An appreciation of the deflationary implications of the current phase of the credit cycle requires an understanding of how bank credit fluctuates and the predominantly psychological factors that drive it.

The Origins Of Bank Credit

The general public is not aware that there are two separate sources of money. The central banks are empowered to issue money, but commercial banks do so as well. One way they do this, is by taking in deposits and then lending them to borrowers for an interest rate return. When the borrower draws down the loan to make payments, more deposits are created as the payments are made.

A second course of money creation is simply by lending money into existence. In this case, the loan is created first, and as it is drawn down, deposits are created. This is regarded as the more usual practice, hence the description of the process being ‘the expansion of bank credit’. Any imbalances that arise between banks are resolved through the interbank market.

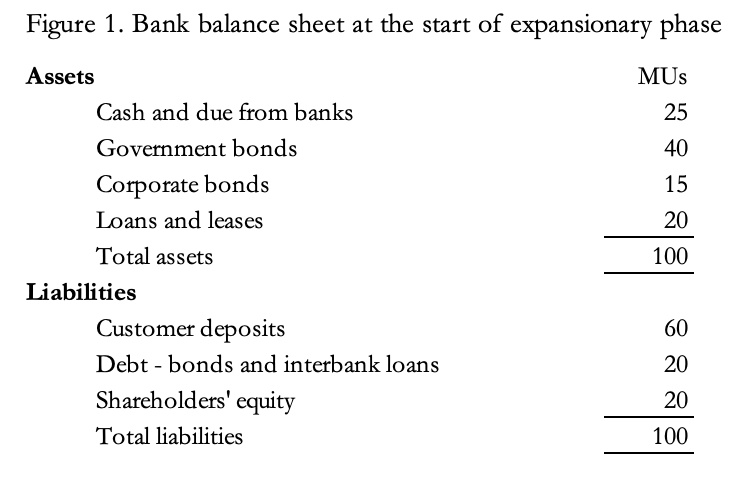

By these means a bank’s own capital becomes a fraction of the bank’s expanded liabilities, hence the term fractional reserve banking. Figure 1 shows the barebones of fractional reserve banking, with a bank’s balance sheet measured in monetary units (mu), early in a phase of credit expansion.

This balance sheet reflects a cautious approach to bank lending. Shareholders’ equity is valued at one third of customers’ deposits and is covered twice by government bonds, (which will all be less than five years to maturity) and is regarded in the banking system as the risk-free investment standard.

At this stage of the credit cycle, and with the banking community generally risk-averse, lending margins are profitable. The ratio of total assets to shareholders’ equity is five to one. Put another way, profits and losses from changes in asset values are multiplied five times at the shareholder level.

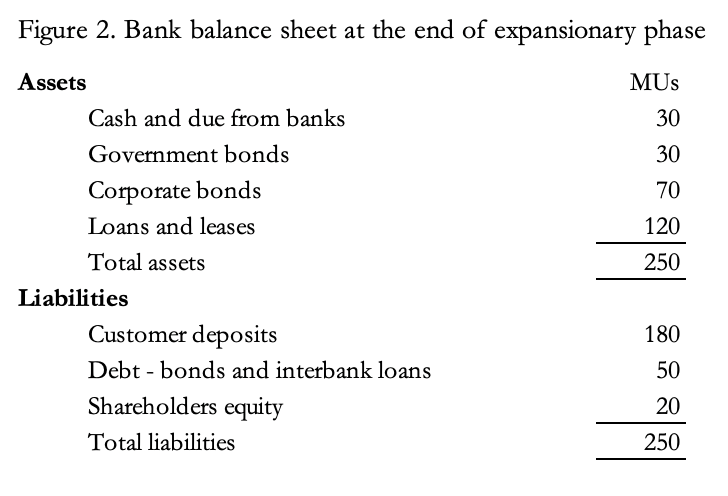

Figure 2 shows the same bank’s balance sheet towards the end of the expansion phase of the credit cycle.

Boom Times

The economy has responded to both monetary stimulation from the government’s deficit spending and interest rate suppression by the central bank. The cohort of bankers has seen a lessening of lending risk, and has responded by actively seeking lending opportunities among large corporations. Bankers are now lending increasingly to medium size corporations as well as investment grade rated borrowers (where the margins are better). Falling unemployment and growing economic confidence decreases lending risk for credit card and other consumer debt, and the bank has extended additional credit for creditworthy customers. Liquidity from government bonds and bills has been drawn down in order to increase allocation to higher-yielding corporate debt. The balance sheet has expanded to give an overall gearing on shareholders’ equity of 12.5 to 1.

This means a two per cent margin averaged across total assets yields a 25% profit on share capital. But by the time this snapshot is taken, competition from other banks will have likely reduced lending margins, and the bank will have responded by taking an even more aggressive lending stance. Lending margins overall are likely to be less generous than at the start of the credit cycle, and loan quality will have deteriorated.

While shareholders are enjoying excellent returns, it has become a highly risky situation for the bank. The slightest pause in the economic outlook, whether from interest rates being raised by the central bank in an attempt to control the boom, or an exogenous factor, such as trade tariffs being raised between the bank’s jurisdiction and a major trading partner, will cause the directors of our bank to switch from greed to fear in a heartbeat. In our example, all it takes is losses of 12.5% of the bank’s assets to wipe out shareholders’ equity.

Contagion

If one bank suspects there may be a deterioration in trade conditions, it is certain that others will as well, because they have similar business information. Due to the dangers of balance sheet gearing, bankers are exceedingly prone to groupthink.

When it happens, the switch from greed to fear travels like wildfire. But some banks are likely to be caught out, trying to increase the size of their bank by being aggressive lenders, (often with a chief executive on an ego trip). Fred Goodwin at Royal Bank of Scotland was a recent example: Ignoring all signs of the ending of a cycle of credit expansion, Goodwin pushed through a consortium takeover of ABN-AMRO in October 2007, with RBS’s portion funded by debt. The bank’s balance sheet gearing became twenty-four to one.

With gearing of that sort, very little needs to go wrong to wipe out shareholders equity, which is what happened. Failures of this type are an acute risk when the banking cohort has been lulled into a false sense of lending risk by a prolonged period of business stability, combining with the siren’s beckoning of a financial bubble.

Reducing bank balance sheets without creating economic instability is virtually impossible. Driven by their groupthink, frightened bankers will seek to reverse credit expansion all at the same time. They sell corporate bonds in a market with no buyers. Spreads, the difference in yield between government bonds and riskier corporate debt, blow out, catastrophic for book values. Business and personal loan facilities are capped and withdrawn, driving many companies into the hands of insolvency practitioners. It can become a race between bankers to reduce the size of their balance sheets before their competitors, as the rapid withdrawal of bank credit triggers bankruptcies and unemployment. It has happened repeatedly for the last two hundred years.

The economic effect was summed up by economist Irving Fisher in the 1930s, who is forever associated with the theory of debt deflation. As the oxygen of credit is withdrawn, businesses get into trouble and banks begin to liquidate collateral. Liquidation of collateral drives their values even lower, exposing additional formally secured lending as no longer secured. Further collateral sales follow, driving collateral values down even further. And so on.

That was in the depression years, and Fisher’s point was to link the collapse of businesses, asset values and also the failure of banks themselves with the contraction of bank credit. Subsequently, central bank policy has focused on trying to anticipate and stop the deflation of bank credit in the first place, always ready to turn on the money spigot. The government then subsidises the economy by increasing its spending without raising taxes. By using the stimulus of unfunded government spending and central bank money creation, the government and its central bank are following the Keynesian economic playbook, which now sets the relationship between the state and private sectors.

Despite everything attempted by statist intervention, we still have periodic bouts of bank credit deflation. But matters have evolved from the simple model illustrated in Figures 1 and 2 above. Banking has become highly regulated, and banks now lend on a formulaic basis, set globally by the Basel Committee (we are on rules version 3) and by local regulators.

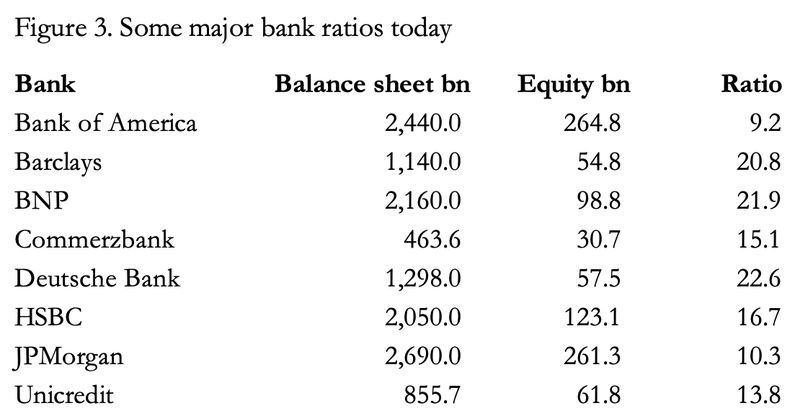

Earlier versions of these controls permitted Fred Goodwin to take the RBS balance sheet gearing to credit hyperspace. They say lessons were learned, but the only lessons learned by the regulators were new ways to keep their eyes shut and ears plugged. Stress testing of bank balance sheets assumes little more than a moderate recession and denies the likely consequences of anything worse. The economic crisis starts with a change in banking cohort groupthink, and not, as regulators with their useless stress tests assume, a decline in GDP, a rise in unemployment, a rise in price inflation, or Heaven forfend, an unexpected financial crisis. And if you think extreme bank leverage would have been controlled following the Fred Goodwin episode, think again. Figure 3 shows current balance sheet to equity ratios for a selection of major banks. Through the magic of modern accounting practice, they are almost certainly higher than reported.

From the few examples in Figure 3 we can anticipate bank failures to originate in Europe in the event of a general contraction of bank credit. Despite reducing its balance sheet significantly in recent years, Deutsche Bank is in Fred Goodwin territory, closely followed by BNP and Barclays. And the credit cycle has very obviously turned down again. The regulators persist in behaving like the three wise monkeys, wholly unaware there is a credit cycle and what these ratios indicate.

The large American banks are not so heavily geared, but that will not protect them from the global credit contraction that will now intensify.

Enter The Coronavirus

We have made the important point that even before the coronavirus lockdown, the credit cycle was already turning down. Liquidity strains had surfaced last September, with the Fed routinely supplying tens of billions of dollars of liquidity through the repo market.

The monetary base, which represents the quantity of money in public circulation created by the Fed, is now growing at the fastest pace on record. But since January, a new problem arose: the disruption to production supply chains from the virtual shutdown of Chinese production due to the coronavirus.

The manufacture of anything requires multiple inputs, commonly referred to as supply chains. The concept of a supply chain suggests they are one dimensional: a series of production steps that go towards a single product. This is not the case. Supply chains are multidimensional and involve supplies from many sources in many jurisdictions at every production stage. The sequential shutdown of China, South Korea and much of South East Asia was followed by Europe, Britain and America. During these shutdowns almost all production and sales of non-food goods and non-essentials ceased.

While the assembly of a product progresses in one direction, payments flow backwards down the chain as each production step is delivered. The sum of the payments involved is far greater than the value of the final product. The global payment disruption is therefore significantly greater than the GDP number, which only consists of the sum total of final products bought by consumers. In the case of the US, an approximation of domestic payment disruption is contained in the gross output statistic, which is $38 trillion compared with a GDP of $21 trillion.

The US economy is significantly services-driven, with shorter supply chains on average than an equivalent manufacturing-based economy, such as China or Germany. If you add together supply chain payments abroad that feed into final goods sold in America, total payments for intermediate production stages in dollar-driven production probably add up to more than $50 trillion, the majority of which are now frozen.

To understand the impact of this new factor on bank credit, we must divide business customers into two classes; those with cash and those that depend on bank loans for working capital.

Both categories have establishment and other costs that continue despite the collapse in production. Those with cash liquidity draw it down to make payments, reducing bank deposits, which are recycled into other deposits which may or may not be with the same bank. When those deposits reduce existing overdrafts, bank credit contracts reflecting a loan repayment. When they amount to a simple transfer of deposit ownership, they do not.

The greater problem is with businesses that need loan cover for missed payments. There are so many of them with payment failures, bankers are being overwhelmed. Whether they realise it or not, they cannot afford to say no to demands for credit because Irving Fisher’s debt deflation problem is so urgent that to deny loan requests would likely end up wiping out the banks’ own shareholders’ capital and then some.

Supply chain payment failures are becoming a banking problem many times larger than the banking cohort shareholders’ capital. The ratio of US gross output to total equity capital for commercial banks in the US is nineteen times. In other words, unless the Fed can increase base money by at least that and somewhat more to compensate for a degree of bank credit contraction, the economy and the banking system will almost certainly crash.

In Germany, where the two major private banks shown in Figure 3 have balance sheet to equity ratios of 15.1 and 22.6, supply chain disruptions seem certain to lumber them with a fatal combination of dramatically widening commercial bond spreads and payment failures from the mittelstand.

Everywhere else, the problem is the same. The Fed has responded by reducing the cost of drawing down established central bank liquidity swaps lines, but they were only available to the ECB, the Bank of Japan, The Bank of England, Bank of Canada and the Swiss National Bank. Recognising the wider problem, on 19 March the Fed extended swap lines temporarily to the central banks of Korea, Australia, Brazil, Denmark, Mexico, New Zealand, Norway, Singapore and Sweden for six months. A notable absentee from the list is China, which one would have thought is the most important user of dollar liquidity based on trade. Politics trumps the delivery of monetary policy in defiance of the scale and urgency of the crisis.

The problems facing the whole banking system have never been greater. Individually, commercial banks are bound to take every opportunity to reduce their risk exposure before the market values of collateral, particularly equities, corporate debt and both residential and commercial property categories fall further in value. Banks will attempt to reduce their interbank exposure, particularly to European banks. Eurozone banks are likely to be the first to fail, needing state bail outs. Counterparty risk in over-the-counter derivatives becomes a major concern for all. And central banks are on a wing and a prayer if they think commercial banks will simply ensure liquidity gets to the right places in time to prevent a financial crisis.

The Final Crack-Up Boom

The Fed and other central banks can only blag solutions to a rapidly debasing currency, but the commitment to maintain financial asset values by printing money in the manner of John Law three hundred years ago will require such enormous amounts of base money as to bring forward the destruction of the fiat dollar and all the other fiat currencies. Banks will have fought for survival in this changed world, with many of them succumbing to public ownership.

In this rapidly deteriorating environment, it won’t be long before the smarter bankers realise that they can deploy the expansion of bank credit to acquire not financial assets, which will become worthless being priced in worthless currency, but real assets. The model adopted is likely to be that of Hugo Stinnes, who in 1920-Germany was known as the inflation king. Stinnes borrowed rapidly depreciating marks to buy up factories and property, amassing an empire of 4,500 companies and 3,000 manufacturing plants. Stinnes died in 1924, the year after the great inflation, and his empire subsequently collapsed.

Banks emulating Stinnes have an additional advantage. They can make acquisitions as principals by expanding bank credit again when they are confident that repayments when falling due will be worth significantly less. Bankers under the cover of nationalised banks might even direct the expansion of bank credit into newly created vehicles in which they have personal interests. This behaviour is atypical and might even have the support of a hapless state desperate for any form of financial stability.

This last act, the restoration of bank credit in its relationship with base money will add a rising multiple of the trillions of central bank base money scheduled to be issued in the coming months and will be a vital component of the crack-up boom with which all currency collapses end. The role of the banks as the medium with which the state seeks to tame free markets will ultimately hasten the end of the fiat currencies from which they have profited so much, and the end of central banking as well.

[i] This was even confirmed in a Zerohedge report this morning (9 April) that JP Morgan halts all non-government guaranteed small business loans.