Who Pays For IT Outages?

Friday, 07 November 2025By Gill Ringland & Patricia Lustig

A number of our previous Pamphleteers have explored the potential damage to the economy and society from IT failures, and our lack of awareness of the extent to which we depend on them.

- Global Risk – is Software The Vlieg in de Soep*? (Sept 2020)

- Digitalisation, Risk and Resilience (June 2022)

- Software – the Elephant in the Room (Nov 2022)

- National Resilience and Threats from Software Failure (Dec 2023)

- Are Digital Systems Fit for Purpose? (Apr 2024)

In the last weeks of October 2025 both Amazon Web Services (AWS) and Microsoft had major global outages, impacting many organisations and end users.

These IT failures have prompted us to ask the question – when IT systems are not available for any reason (cyber-attack, IT outage due to overload, user error or …) who bears the cost? And how might they be recompensed?

Some facts

The AWS outage on October 20th lasted for over 15 hours. It affected millions of people during that time. Websites, apps, tech products and critical communications systems like electronic hospital records were offline.

“AWS revealed a cascading set of events brought down thousands of sites and applications that host their services with the company.

Platforms including Signal, Snapchat, Roblox, Duolingo, as well as services such as banking sites and the Ring doorbell company were some of the 2,000 companies affected by the outage, according to Downdetector – a site that monitors internet outages – with more than 8.1m reports of problems from users across the world.”

The Microsoft outage on October 29th lasted over 8 hours. User reports of outages to Downdectector were in the tens of thousands. The outage affected business users of Office 365 and Outlook, including organisations from supermarkets, banks, corporate users, gamers and Heathrow Airport to retail outlets, mobile phone operators and UK government offices.

Cloud services are dominated by three suppliers. So we need to understand why these outages are happening to cloud services, and ask what sort of strategic thinking might have prevented them?

What is happening?

These two examples, following on from others, such as the Microsoft Windows outage in July (which was due to a flaw in the Crowdstrike system), illustrate three weaknesses of current IT systems such as the cloud.

The first is the complexity of the supply chain and the use of common components across many platforms, of which CrowdStrike Falcon is one. The outage of Microsoft Windows was triggered by a flaw in CrowdStrike Falcon.

The second is the sheer volume of traffic and how interdependent parts can get maladjusted if one gets overloaded, with cascading impact. In the AWS case these interdependent parts were managing access to domain names.

The third is the need to upgrade components of the live system as new versions are produced to handle known problems or to add functionality. Microsoft believed the outage in October was caused by a systems change with unintended consequences. Nearly half of the outages reported by UK banks over two years were due to failures of upgrades.

What is common to these examples? It is clear that failures cannot be completely prevented in complex systems.

What might limit the impact of failures on user organisations? The technology to do this is called resilience engineering and has a number of components for instance:

- Stress testing of systems using high throughputs to cause failure

- Testing the ability of the system to degrade gracefully rather than shutting down completely.

- Isolating any systems being upgraded - for instance introducing in only one geography – so that failures are localised.

User organisations can and should be aware of their exposure and take steps to ensure the availability of their services to their customers despite supplier failures. But in the meantime, costs are often estimated in the media to be in $ billions. Who pays for this? Currently the costs fall on the service provider and their customers.

Who bears the cost?

What mechanisms are there for accountability?

Legislative provisions for health and safety, theft, fraud, and bribery are designed to hold directors accountable for misdemeanours committed by their companies.

Should directors be held liable for failures of IT services to their customers?

Currently, Registered Data Service Providers in the UK are covered by regulation, with fines administered by the ICO for violations of personal data rights. The higher maximum amount is £17.5 million or 4% of the total annual worldwide turnover in the preceding financial year, whichever is higher and applies to any failure to comply with any of the data protection principles. Directors can be disqualified by the ICO if fines are not paid.

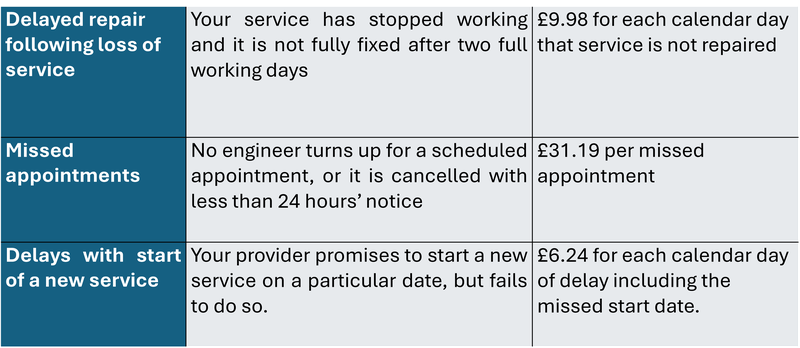

Could similar provisions apply to failure to provide services to publicly visible service level agreements between suppliers of IT systems and their users? There is a precedent in that Ofcom in the UK publish a schedule of payments to individuals under failures to meet stated service levels:

These payment levels set a welcome precedent for defining a contractual service level for IT services. But they do not reflect the potential cost, or damage to life or health, to a user from lack of a phone service.

The BCS has argued that legislation for IT resilience should be modelled on that for health and safety: this would ensure that Directors took responsibility and it would reflect the integral part that IT services play in our economy and society.