The Law Of Unintended Consequences: "Why OTC Derivative Reform And Basel III Will Not Bring The Financial Patient Back To Health"

Tuesday, 26 November 2013By Adrian Berendt

Regulatory Proposals Don’t Meet Objectives

The G20 response to the financial crisis has been to demand an increase in the amount of capital for all derivative trades and to incentivise clearing through a CCP, whilst recognising the latent risk in a CCP, via a mixture of financial incentives and compulsion. Unfortunately, the actual measures proposed by regulators to meet these demands will achieve the opposite of what was intended. They will not increase the stability of the financial system. At best they will achieve nothing; at worst they will lead to more instability.

Stop Before It's Too Late!

Basel III needs a radical rethink in four ways, even before it’s introduced:

- Do more to simplify the objectives and strip out the complexity introduced by Basel II

- Avoid the financial disincentives to clearing by removing the charge on CCP Default Funds

- Don’t impose the clearing obligation

- Introduce the new rules simultaneously

A Health Primer

Forgive the medical analogy, but it helps. Getting a drug addict to kick a habit that they didn’t intend to acquire in the first place involves encouraging the patient to acknowledge the problem, prescribing the right medicine and providing incentives to support good behaviour. At the behest of politicians around the world, the doctors in Basel are encouraging the financial system to keep its habit hidden, are prescribing the wrong medicine and giving no incentive for financial firms to stay clean. The measures needed are ones that will change behaviour. Introducing new laws (rules) that the addict (the financial institution) doesn’t like will lead to foreseeable but undesirable consequences.

A History of Mistakes in (Basel) 3 Episodes

Episode 1: the 1st Capital Accord

Enough of medicine, about which I know little. Instead, a brief history lesson, informed by a little 20-20 hindsight. Up until the 1980s, it had been up to executives in commercial banks to run their firms prudently, assessing their risks and taking care that they had sufficient liquidity. Returns on capital for the public firms were expected to be low for such prudent institutions. Some of the riskier institutions – the private partnerships – didn’t even need to make their capital positions public as they didn’t expect the taxpayer to bail them out if they got into trouble. The then G10 was becoming concerned that competition was driving capital levels to a level that was too low[1] and introduced the 1st Basel Capital Accord[2] as a way of establishing an adequate level of capital and creating a “more level playing field”[3]. The 1st Capital Accord was not about absolute safety but about removing some risks and injecting fairness into the competition. The Accord had an additional virtue – its limited scope made it low in complexity. Running to 28 pages, it was a document that most professionals could understand.

With the benefit of hindsight, it was almost inevitable that we should want to extend the scope and to fine-tune the Accord to address its perceived flaws. Why? Human nature! First, we are unable to resist tinkering with ideas which seem good at a particular point in time. Secondly, what gets measured gets manipulated. Firms now had to keep an eye on two measures of capital – regulatory and economic. Bit by bit, the importance of regulatory capital increased and firms sought ways of enhancing returns on that capital.

Episode 2: Basel III and More Complexity

Basel 1 allowed firms to increase regulatory leverage because it “missed” whole swathes of risk – market risk, derivative credit risk – and for those risks that it did cover – mainly banking book credit risk – the weightings attached to assets were deemed to be insufficiently accurate. Never mind that the original Accord was never intended to be an enterprise-wide risk management tool.

In 1996, Basel I was extended to include market risk, but no adjustment to credit risk weightings. “Not enough”, said the risk management community, “we need more accurate risk measures” … and in June 1999, the first consultation on a new framework was launched. Irrespective of the deficiencies of the 1988 Accord, merely weighing the final document’s 333 pages should have told us that the seeds were being sown for the major policy error entitled Basel II. A whole new advisory industry was born to explain its complexities and to explore its deficiencies.

Episode 3: Two Mistakes In One

Hardly had Basel II been introduced – and in many parts of the world it hadn’t been implemented at all – and along came the financial crisis. Politicians and regulators rushed to bring in Mistake Basel III, prescribing two changes: 1) fill in the perceived holes in Basel II with a further 136 pages – 68 each on capital and liquidity; and 2) turn the whole OTC Derivatives market upside down – two mistakes in one.

Mistake number 3 is partial: one largely positive impact, two negatives and one in the balance:

[+] The reliance on risk weighted capital measures is diluted by the introduction of a leverage ratio;

[-] Increasing the amount of capital may not make the financial system safer. Some argue that it was too much capital chasing too little safe income that led banks into risky lending in the pre-2007 period;

[-] No financial incentive for clearing – see below;

[+/-] Increasing the reliance on non-model approaches may mitigate model risk but potentially reduces the risk sensitivity of exposure measurement and lead to more risk lending.

Mistake number 4 ranges from the multiplicity of reports, which regulators find hard to use, to the unintended consequences of mandating products for clearing.

"Clearing's a Good Thing...

I declare an interest at the outset and believe that, although no panacea, clearing is helpful if used in the right dosage and circumstances. It can increase transparency and standardisation and, in times of trouble, can make crisis resolution easier to manage – witness Lehman, where cleared trades were resolved more quickly than uncleared ones. Clearing works really well where the products are standardised and the market has a limited number of active participants.

... But Not if it's Mandated!"

Mandating the wrong markets or products risks causing the next financial disaster. Either an unsuitable product will be cleared and a CCP will blow up, or participants will simply not trade cleared products/markets. This will result in one of three outcomes:

- More complex instruments will be developed which avoid the mandate;

- Trading will transfer to less highly regulated markets, or

- Corporates will choose to not hedge particular risks. None of these three outcomes is what the G20 intended.

The Reality of OTC Market: What’s Already Cleared and What Won’t Be

Even if these outcomes are avoided, it’s hard to see that much additional volume will be cleared[4].

Interest rate derivatives form the largest OTC Derivative asset class by outstanding notional – some 77% – of which 76% are interest rate swaps. SwapClear dominates this market, already clearing more than 50% of IRS, without the obligation or financial incentive from regulators. Since the more complex instruments are unlikely to be mandated, introducing financial disincentives to clearing, as proposed, will reduce rather than increase the likelihood of such products being cleared.

The asset class with the second biggest market share by outstanding volume at about 11% is FX, which has the largest daily turnover. Regulators have exempted the majority of FX trades from the clearing obligation on the basis that CLS mitigates the majority of risks. Whether or not CLS does so is the subject for another day. Similarly, it will require a financial incentive for significant volumes in this market to be cleared.

That leaves about 12%. Credit comprises 4%, where many of the simpler products are already cleared and the rest might prove too complex to clear. That leaves commodities, where some clearing exists, but where volumes are relatively small.

The opportunity for an increase in interdealer clearing due to EMIR/Dodd Frank or Basel III seems to be rather limited since most volume is either already being cleared, is exempted by regulators or is likely to prove too complex to clear.

Turning to client clearing, the financial benefits of clearing for the end-client or for the financial system as a whole are dubious. In the first place, for interest rate and FX derivatives, non-financial firms account for less than 10% of market share, many of whom will be likely to be exempt. Secondly, the financial logic for clearing trades through a CCP rather than settling with a bilateral counterparty is unconvincing. Clearing brings big benefits to a market and its participants where multilateral netting reduces the number of offsetting trades. The multiplicity of end users, many of whom may want their trades held in separate Individually Segregated Accounts, negates this potential benefit. If there is no financial benefit, then compulsion will result in four consequences – largely unintended:

- Additional costs for those end-users that are not exempt from the clearing obligation;

- The development of new “non-standard” products to avoid the obligation;

- Trading in locations with less/no regulation; and/or

- End-users carrying the risk previously hedged in the market.

All-in-all, a recipe for less transparency.

How and Why Basel III Brings No Financial Incentive For Clearing Through a CCP

As we have seen, the G20 demanded increased capital for derivative trades, financial incentives for clearing through a CCP and recognition of the latent risk in a CCP. Although the Basel III proposals meet objectives 1 and 3 – the total capital for derivative trading will increase substantially and capital is charged for CCP exposures – they fail to satisfy objective 2. The cost of capital for Default Fund contributions are a significant disincentive to clearing and are unlikely to outweigh the, harder to quantify, collateral savings. For those institutions whose constraint is the Leverage Ratio, the equation is more balanced, but there is still no clear financial benefit to clearing.

[+] Basel III attempts to meet the G20 objectives by tightening the rules on capital and risk weights – typically >20% for interbank trades – for bilateral exposures and by applying a 2% risk weight on banks’ Trade Exposures to CCPs.

[-] A further level of “security” has been added by mandating the exchange of collateral, on a bankruptcy remote basis, between counterparties for non-cleared trades. This has the, probably unintentional effect, of reducing the capital needed for non-cleared trades to a negligible amount. Since members will have to hold capital against their CCP Trade Exposure, MORE capital will be needed for cleared than for non-cleared trades, even with the lower 2% risk weight.

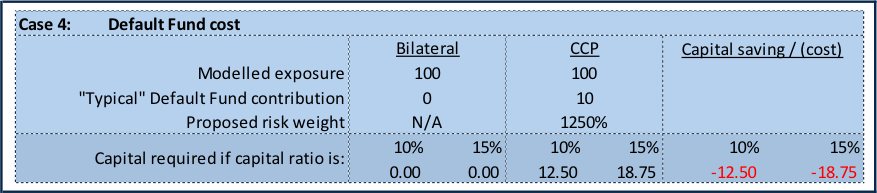

[-] Even this amount is small, compared with the cost of holding capital for Default Fund exposures. Under the proposals issued on 26th June 2013, members would have to hold capital of at least 100% of the amount contributed to the Default Fund – equivalent to a risk weight of 1250%. This makes clearing even more capital intensive than the equivalent bilateral exposure.

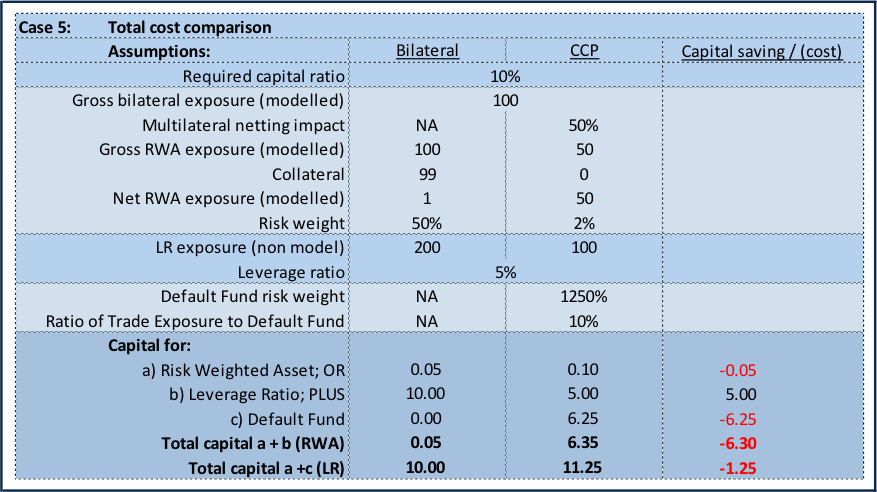

Let’s take an example: assume that a firm has a net exposure before collateral of 100 towards its bilateral counterparty. Under the proposed new regulations, each party will place collateral with the other in bankruptcy remote arrangements. The amount of collateral is intended to cover current replacement cost plus potential future exposure arising over 10 days following the default of the counterparty (to 99% certainty). The remaining exposure is, therefore, likely to be small – let’s say 1. Assuming a counterparty risk weight of 50% and a capital ratio of 10% - minimum of 8%, up to 15.5% – the amount of capital will be 1 * 50% * 10% or 0.05 for an exposure of 100.

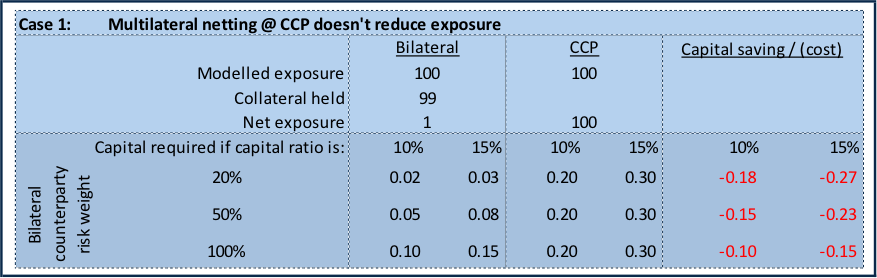

Exposures towards a CCP attract a 2% risk weight, but with no offset for collateral, since the CCP does not place margin with the counterparty. The capital required for the exposure in the example above is, therefore, 100 * 2% * 10%, = 0.2 – 4 times as much capital as the equivalent bilateral exposure. Table 1 shows the outcome if it is assumed that clearing through a CCP brings no exposure reduction from multilateral netting.

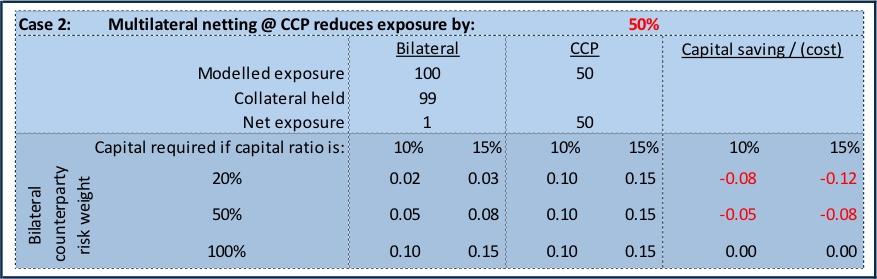

Table 2 shows the outcome if clearing through a CCP reduces exposure by 50% – a plausible figure.

Leverage Ratio Changes the Game for the Financial Industry

In addition to holding capital based on risk weighted assets, banks will be required to limit overall exposures using a Leverage Ratio (LR). The LR potentially transforms the calculation for derivatives as it differs from the risk weighted approach in three important ways:

- The LR ignores risk weightings and requires banks to hold between 3% and 6% of gross assets[5], i.e. 3 of capital per 100 of gross exposure.

- The risk weighted asset ratio takes into account collateral, whereas the LR excludes it.

- For derivatives, banks can use an internal model to calculate their risk weighted exposure; Basel III proposes to use a non-model approach – entitled NIMM. Although the calibration is not yet finalised, a reasonable assumption is that the NIMM exposure might be twice that calculated under an internal model – say 200, rather than 100.

The capital for a bilaterally settling portfolio similar to the earlier example would be 200 * 3% = 6, compared with 1 * 20% * 10% = 0.02, or 300 times as much capital!

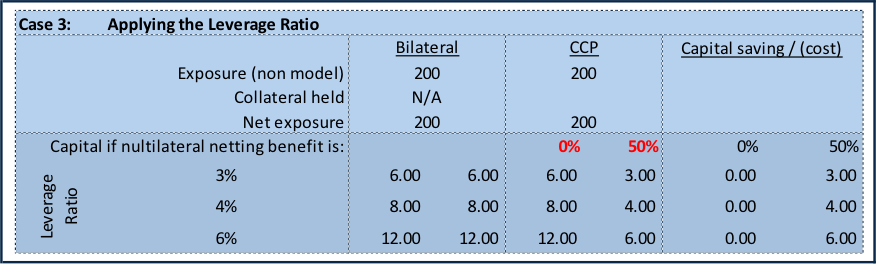

Applying the Leverage Ratio for exposures to CCPs as well as other counterparties makes the 2% risk weight redundant. Table 3 shows how there may be some capital savings from clearing trades, depending on the benefit of multilateral netting.

The LR will typically impact those banks with a high proportion of assets in the trading book. Banks with large banking books with higher average risk weights will tend to produce a higher capital charge using the Risk Weighted Asset Capital measure. For investment banks, the LR will become the capital driver, particularly in the US, where the LR is 6%, rather than the 3% proposed by Basel.

And That’s Not All…

If that weren’t bad enough, the timing of the BIS regulations may also check G20 aspirations, depending on their implementation in individual jurisdictions. Whilst the BIS plans a new “more risk sensitive” non model approach – NIMM – it is unlikely to be implemented before 2015. In the meantime, banks in some jurisdictions are being asked to account for their LR under the old, risk insensitive, Current Exposure Method (“CEM”), which can overstate exposures by 10 times. This could increase capital for some assets classes – particularly interest rate swaps – under the LR by five times the amounts shown in Table 3 above.

Cost of Capital For Default Funds Kills Clearing

Even if the LR reduces the comparative cost of capital for cleared trades, the cost of capital for banks’ default fund contributions makes clearing uneconomic, contrary to the G20 intent. Although Default or Guarantee Funds vary between CCPs, both in terms of financial contribution size and in legal constructs, it is not unreasonable to model a fund size at 10% of Trade Exposure. The current proposals, issued by the BIS in June 2013 are for a minimum risk weight of 1250%. In the example given, for each 100 of exposure, a bank might have to hold capital of 12.50 to 18.75, depending on the capital ratio required by the individual regulator, as show in Table 4.

Table 5 summarises the position, showing how capital required for a cleared portfolio exceeds that for an uncleared portfolio, whether it is the RWA or the LR that constrains capital.

Why it is Not Logical to Hold Capital Against the Default Fund

Regulators assume that Default Fund contributions carry risk. On the face of it, the argument is seductive: A bank that has placed funds with a CCP should hold capital against the risk that it might not get the funds back. However, the real risk is that a counterparty (bilateral or CCP) defaults. Contributing to a Default Fund is a MITIGANT of that risk, as can be seen in the following simple case.

Step 1 – Counterparty A trades with B and each places collateral with the other. Capital of x is needed to cover any residual uncollateralised exposure.

Step 2 – trade is novated to a CCP, which requires the same margin. Same trades in the system, same collateral. Since CCPs reduce systemic risk – per G20 – the amount of capital ought to be less than x.

Step 3 – firms are required to contribute to a Default Fund. This reduces the systemic risk further, as there is now more risk bearing capital in the system and total capital must reduce further.

Regulators need to rethink this part of their proposals completely.

Postscript: Some (Limited) Benefits to Clearing from Reduced Collateral

Multilateral netting means that the amount of collateral to support derivative portfolios is potentially smaller in a cleared versus a non-cleared world. Quantifying this benefit is difficult, as there is no consensus about the cost of collateral. It depends on:

- The benefits of multilateral netting,

- The balance of cash versus non-cash collateral, and

- The cost of that collateral.

References and Notes

- Bank for International Standards. (2001). “The major impetus for the 1988 Basel Capital Accord was the concern of the Governors of the G10 central banks that the capital of the world’s major banks had become dangerously low after persistent erosion through competition.” — 'The New Basel Capital Accord: An Explanatory Note'. Last accessed October 2013.

- Bank for International Standards. (1988). 'Basel Committee on Banking Supervision: International Convergence of Capital Measurements and Capital Standards'. Last accessed October 2013.

- “The two principal purposes of the Accord were to ensure an adequate level of capital in the international banking system and to create a “more level playing field” in competitive terms so that banks could no longer build business volume without adequate capital backing.” — Op cit. n1.

- Source for figures:

- Bank for International Standards. (2013). BIS Quarterly Report June 2013. Last accessed October 2013.

- Swapclear. What We Clear. Last accessed October 2013.