The Power Of Paradox

Monday, 09 October 2023By Chris Yapp

Have you ever thought about having your own eponymous concept or brand? Two recent examples, overheard made me think of the power of such brands:

First, I heard a woman on the phone asking someone to get the Dyson out and do the Hoovering. Second, I had an email from someone who had found me by Googling on Bing.

Back in the 1980s, one powerful concept, “ The Solow Paradox” helped shape 20 years of my career. Robert Solow, the American Economist famously stated in 1987 that: “You can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics.”

Work at Sloan School, MIT around this observation created the concept of re-engineering, popularised by Michael Hammer in 1990 in his article, “Don’t Automate, Obliterate”.

There is no silver bullet to answering the paradox with many themes contributing to the difficulty. In part, measuring the wrong things, winners and losers cancelling each other out, mismanagement, lags between investment and returns have all been argued to contribute to the difficulty that Solow identified.

I remember the first time I presented to the directors of a large organisation on the paradox. The CFO argued that he had delivered and his fellow Directors had not. Unfortunately, I knew what was coming next. The organisation had conducted an Activity Based Costing exercise, ABC, to determine it’s sources of cost and value.

On one hand the returns in Finance looked impressive. Headcount had fallen by more than 50% and they had sold some surplus buildings on the back of efficiency gains. However, the ABC exercise showed that the operating departments were now doing work that had previously been done inside Finance. In effect, automation of the finance function had increased overall costs by exporting the work to other departments.

Since the 1980s there have been important developments which put IT in the context of previous waves of technological innovation. Carlotta Perez, in her book “Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital: The Dynamics of Bubbles and Golden Ages” identifies a repeating pattern of 2 cycles of a bubble with a focus on investment in the new shiny toys, followed by a wave of investment delivering the productivity gains.

On the measurement side, Robert Kaplan’s books “Relevance Lost” and “Balanced Scorecard” indicated how accounting practice had failed to adapt to the changing world. I would add Robert Gordon’s “The Rise and Fall of American Growth” to a reading list to grasp the longer term challenges. If you need some optimism about the future I would recommend Tyler Cowen’s work.

So, let me return to my initial question. Can you find something that is increasing that should intuitively be contributing to productivity gains, but does not appear to be doing so?

If you can, you can create your own eponymous paradox in the style of Solow.

The UK consulting market is around £14bn p.a, and Globally, management consultancy is worth over $160bn. Growth rates over the period to 2028 are predicted to be around 4.25%. There are very few countries where productivity growth is anything like 4.25%. Let me put it another way. If productivity was growing faster than management consultancy and you were a spokesman for the sector wouldn’t use that as evidence for the value added of consultancy?

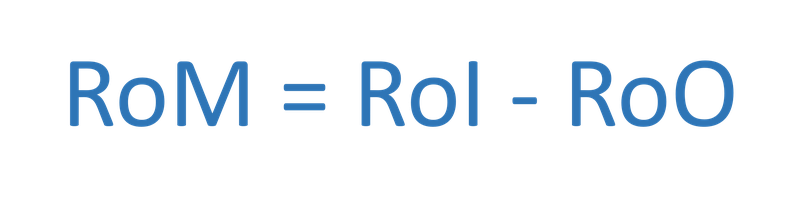

This makes me recall another thinker on these issues, Paul Strassmann. I had the privilege and pleasure of hearing him on 2 occasions. His arguments are detailed and evidenced, but in a simplistic way, his argument was that Return on Management, ROM was what was left over when you took Return on Operations away from Return on Investment.

He gave examples of organisations and indeed industries where RoM was negative!

So, the Yapp paradox could be “You can find Consultants everywhere except in the productivity statistics”.

The economist Marianna Mazzucato is critical of the role of Consultancies in the modern economy. This year, her book “The Big Con” outlines her case for the prosecution. Personally, I don’t think that it’s her best book, but the response to her arguments have not been strong.

In an earlier post on Pamphleteers I used the Sherlock Holmes example of the dog that didn’t bark around another critique by George Soros on Financial Markets that didn’t get the reaction that might have been expected.

I am sure that you can find many other examples. For instance, growth in executive pay consistently exceeds productivity improvements. Yet ministers make speeches which argue that wage increases have to be earned by productivity improvements. I remember hearing W Edwards Deming in the 1980s showing a chart in one of his lectures which showed that American competitiveness had declined as the popularity of the MBA grew. His observation that “If you learn the wrong things, don’t expect improvement” has stuck with me for decades.

As with the Solow Paradox, there is no single corrective that can fix the difficulty. These are complex multi factorial challenges.

So, how would you feel if taxes on businesses were redesigned to reward productivity gains and reduce the burdens on organisations that could demonstrate real value added?

Such a system could incentivise the laggards to invest and improve to reduce their tax burden to the wider benefit of the economy.

I would be interested to hear what your eponymous paradox might suggest holds us back!