The Maginot Line: iNED Defence Of Value?

Friday, 01 March 2019By Sunil Chadda & JB Beckett

About The APFI

Founded in 2011, the Association of Professional Fund Investors (APFI) was created by and for its membership. The APFI promotes “Best Practice” in fund investing by setting global standards of professionalism and accreditation, whilst empowering professional fund investors to learn, share ideas, network with their peers, and have a collective voice to national and global standards bodies and regulatory authorities.

Introduction

What is the purpose of financial regulation? It builds transparency and, hopefully, trust. Delivering a robust regulatory framework encourages investors to invest more. In doing so, it increases the UK’s savings ratio and narrows the pensions gap. For UK Authorised Fund Managers (AFMs) it enables them to become a centre of excellence, and in turn, the UK becomes globally competitive, attracting both domestic and foreign capital, generating growth and tax receipts for the economy.

2019 will herald new regulatory defences through independent Non-Executive Directors (‘iNEDs’) and Assessment of Value (AoV) disclosure requirements. Indeed, the competence of those new iNEDs will be of interest to Fund Investors, as an indicator of fund governance, as will the resulting disclosures. However, like France’s ill-fated Maginot Line, new regulation can create defences or introduce new weaknesses. Sometimes the deeper the regulation, the wider those weak points become. Therefore, investors, Fund Boards and new iNEDs need to forearm themselves in advance.

The Maginot Line

Following the excellent iNED ‘Bootcamp’ held on Wednesday, 23rd of January 2019 by UK Fund Boards, it was clear to the packed room of 120 prospective and current iNEDs that a vast number of complex issues will arise when meeting the new FCA “Assessment of Value” requirements in September 2019. What exactly do they mean for Fund Investors and Fund Boards?

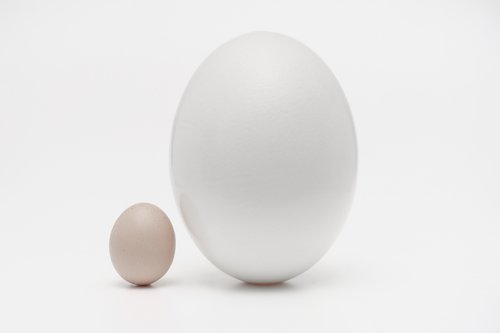

History reminds us that the wrong defences can be as ineffective as no defence at all. The Maginot Line, named after the French Minister of War André Maginot, was a line of concrete fortifications, obstacles, and weapons installations built by France in the 1930s to deter invasion by Germany and force them to move around the fortifications.

Constructed on the French side of its borders with Italy, Switzerland, Germany, and Luxembourg, the line did not extend to the English Channel due to French strategy that envisioned a move into Belgium to counter a German assault. French military experts extolled the Line as a work of genius that would deter German aggression because it would slow an invasion force long enough for French forces to mobilise and counterattack.

The French line, however, was weak near the Ardennes forest and the French believed this region, with its rough terrain, would be an unlikely invasion route for German forces. If it were to be traversed, so they believed, it would be done at a slow rate that would allow the French time to bring up reserves and mount a counterattack. The German Army exploited this weak point in the French defensive front and undertook a rapid advance through the forest and across the River Meuse tactfully encircling much of the Allied force, resulting in hundreds of thousands of troops being evacuated at Dunkirk. The remaining forces to the south were unable to mount an effective resistance to the German invasion of France1.

Background

“Value” – Specifically do funds generate “value” for their investors? Can it be identified, assessed and then reported?

Born out of the FCA Asset Management Market Study Final Report (MS15/2.3) and follow up remedies (PS18/8) in 2018, the “Assessment of Value” (AoV) is an attempt to reinforce fund outcomes via improvements in governance. We consider, from an investor’s perspective, as to how the AoV framework and resultant investor disclosure could function effectively and transparently.

UK Authorised Fund Managers (AFMs) will be required to focus more on their duties as agents of investors and to ensure fair treatment for all Fund Investors. The FCA has built on the Gartenberg principles, which is based on US case law to identify ‘excessive fees’, to then define an ‘AoV’ framework here in the UK.

It is early days though. Fund management firms will be concentrating on: trying to understand what the AoV framework will look like, identifying, sourcing and checking the data that they need to report; defining the reporting format of the long internal analysis; deciding upon the format of the investor disclosure itself; and also recruiting iNEDs for the Fund Board.

We are now at that seminal point where the “penny-pound” syndrome applies – do it properly now and spend a penny or come back in a year or two and spend a pound to put it right - on each iteration. We all might regret not getting it right first time, as the EU is following in the FCA’s2 steps in applying a regulatory framework to assess fund “value” for European investors. We think that the EU will build on the use of pre-mandated information in fund documentation at time of purchase and use it to form the basis of their Assessment of Value. We certainly don’t want our defences being circumnavigated through Belgium.

If you haven’t read it already, then we highly recommend that you read our paper entitled “Investment Costs in Europe: ‘Game of Thrones’”3 first as it provides the context for all subsequent papers, including this one.

Situation Report (‘SitRep’) – Gartenberg & AoV

Why is Gartenberg important? It is clear that the FCA looked heavily at the US experience when designing the AoV regulation.

In 1982 a plaintiff (Gartenberg) sued Merrill Lynch in the US for purportedly ‘excessive fees’ regarding its money market fund, the Merrill Lynch Ready Assets Trust (RAT) which was advised and managed by Merrill Lynch Asset Management, Inc. (MLAM).

An advisory fee was charged by MLAM, which dropped as the fund assets rose.

When compared to like funds, the fund had performed above average. Gartenberg, a shareholder in RAT, filed a derivative action, alleging the fees were so high they were considered a breach of fiduciary duty in violation of section 36(b) of the Investment Company Act. Following a non-jury trial, the action was dismissed once the court found MLAM’s fee to be comparable to fees charged in other parts of the market and so a fair one. Gartenberg then appealed. In 2010, Gartenberg was upheld by the US Supreme Court.

On March 30, 2010, in Jones v. Harris Associates L.P., the United States Supreme Court handed down its much-anticipated decision reviewing Gartenberg. The Court concluded that “Gartenberg was correct in its basic formulation”. With the decision in Jones, the previously influential Gartenberg approach now becomes the authoritative test nationwide in the US in determining when investment-related fees and expenses are excessive. The Court also added further guidance for lower courts to apply in judging whether compensation is excessive.

The affirmed Gartenberg ‘Standard’ is made up of 6 factors that require compensation be examined from multiple perspectives before a finding of “excessiveness” can be made, including at a minimum:

- Services & Quality: The nature, extent, and quality of the services to be provided by the investment adviser;

- Performance: the investment performance of the investment and the investment adviser;

- Costs & Profits: the costs of the services to be provided and profits to be realised by the investment adviser and its affiliates;

- Economies of Scale: the extent to which economies of scale would be realised as the investment grows and other circumstances increase efficiency;

- Benefit to Investors: whether fee levels reflect these economies of scale for the benefit of investors.

- The sixth factor related to the need for “independence and conscientiousness of the fund’s independent directors.”

If you attended the UK Fund Boards events, followed the FCA consultation or our ‘Game of Thrones’ series of working papers then you probably don’t need reminding of what exactly those AoV principles are again, but here they are anyway – all 7 of them:

- The range and quality of service provided to unit-holders;

- The performance of the scheme, after deduction of all payments out of scheme property;

- The cost of providing services;

- Whether the AFM is able to achieve savings and benefits from economies of scale, relating to the direct and indirect costs of managing the scheme property;

- In relation to each service, the market rate for any comparable service provided

- In relation to each separate charge, the AFM’s charges and those of its associates for comparable services provided to clients, including for institutional mandates of comparable size; and

- Whether it is appropriate for unit-holders to hold units in classes subject to higher charges than those applying to other classes of the same scheme with substantially similar rights.

Considerations – Fire In The Hole!

We believe that there are 4 potential areas in which weaknesses in the Assessment of Value will manifest themselves. These are:

I. The AoV Framework;

II. The Forest of Uneven Regulation and Regulatory Metrics;

III. The Difficulties in Benchmarking AoV Principles & Costs; and

IV. An Investor’s Perspective of “Value”.

In the following sections, each of these areas is reviewed in detail.

I. The Assessment Of Value Framework

As stated earlier, the FCA has not specified what format the end 2-4 page AoV investor disclosure should utilise. No cost, performance, risk or other metrics have been specified either. Whilst this allows AFMs a fair deal of flexibility, it also leaves the door open to AoV frameworks that might not suit how an investor invests or views “value”.

AFMs will probably use the same AoV format across their fund stable making it easier to compare and contrast the “value” inherent in their products. An investor, however, may hold an FTSE 250 equity fund managed by two entirely different AFMs and be unable to compare the “value” in fund 1 with the “value” in fund 2, as the AFMs will be using very different content and reporting formats in their AoV investor disclosures. Worst still, the differences may not be obvious to the investor, and that could give rise to inaccurate comparisons and possible adverse outcomes.

It is important to recall that there is a core of 7 AoV principles that must be analysed and reported on – but AFMs could use more if they feel it demonstrates the “value” of the fund to the end investor. For example: low staff turnover rates; experience of senior staff; soundness of business model; past and planned systems and operations improvements and upgrades could all be considered important, but this detail should be supplemental and not be misused to confuse investors should “value” clearly be lacking.

In order to assess “value”, we would expect Fund Boards to consider a broad range of both sensitive and public information – some information will be technical, but only a fraction of which will be reported to the end investor. The danger for the Fund Board is that a clear assessment of value becomes entangled within complex dashboards and other information. Compressing that large internal Fund Board AoV disclosure, that possibly runs into hundreds of pages, into a 2-4 page investor disclosure will take some skill.

Getting it right from the off in the UK is definitely important, as should something go wrong and the AFM face investor disquiet, the cost of defending a law suit for an AFM can be many times the litigant’s costs. The AoV investor disclosure could, arguably, become a solid defence against litigation by adopting a “Best Practice” disclosure format that is in line with the rest of the industry. It is that “penny-pound” syndrome again.

Mechanics: As with any “value”-based analysis, all key inputs (i.e. each AoV principle) should be clearly assigned a weight. Investors buy funds for a purpose - and that is primarily the promised financial return. We believe, therefore, that performance (net of fees) and costs should carry more weight than other inputs as they are “value” indicators that are widely understood and used by investors. Finally, the weighting mechanism used by the Fund Board to assess “value” should be fully visible to the end investor in their annual AoV investor disclosure – to aid understanding.

It is essential that all “value” rating scales and definitions used by Fund Boards to report their AoV are fully defined for the consumer. When describing overall fund “value”, what exactly does “Poor”, “Reasonable”, “Good”, “Medium” or “High” all each mean? This equally applies to all terms, calculation methodologies, measures, and acronyms used in the AoV investor disclosure. Providing a clear, consistent and meaningful context to the findings should make for interesting reading.

In providing that context, Fund Boards should be free to add as much narrative as is practically possible to any of the findings in the AoV investor disclosure, provided that the comments are “Fair, clear and not misleading” (FCA COBS 4.2).

Whatever the framework a Fund Board ultimately considers using to assess “value”, it needs to be thought through so that it is strong enough to stand the test of change over time. We see many potential changes, whether regulatory or other, impacting the AoV framework in the next few years and the chosen framework must be able to cope with them. We would like to see Fund Boards provide a clear explanation to investors as to how they have approached the AoV process together with the rationale for adopting the AoV framework that they have chosen.

Such a statement should also explain exactly how the Fund Board will incorporate any foreseen regulatory or other change that may impact the AoV investor disclosure going forwards – post-live. It may also be possible to identify and plan for other types of changes, such as the investment objective or cost profile of the fund changing materially. If this happens then the Fund Board will need to assess “value” pre and post the change and keep investors appraised as to how this has been reflected in their AoV investor disclosure.

This approach will ensure that investors, and Fund Boards, fully understand how these forthcoming changes will impact their AoV framework and investor disclosure. For the regulator, the existence of such a statement is proof that the AoV framework has been properly thought through and stress-tested.

Measures: An area of contention is the use of measures such as “median” and “mean” – and choosing one measure over the other to sort and report data will give different results. We point to a specific example later on when reporting fund performance v. peer groups. The use of other similar, but not the same, measures, therefore, will only serve to skew findings and confuse the determination of “value”. From closely analysing other industry cost transparency initiatives, we note that other measures, such as “Average NAV” can be open to interpretation too. Depending on how the first AoV investor disclosures are received, clear definitions may be required for any term that is referenced in it.

KPIs: A strong set of Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) should be decided upon and the values sourced to drive the “value” findings for most, if not all, of the 7 AoV principles. Cost, performance, risk, operational, profitability and other statistics (such as differing service types), split by share class, will, no doubt, be required to be evidenced by the regulator to prove a carefully thought-out and transparent process. Such an analysis might point to unexpected areas or anomalies that require improvement or correction. There may be easy wins in there.

The iNEDs on the Fund Board may want to view things from other perspectives so could identify and request additional data sets or information for further analysis. This gives rise to what is and what is not “reasonable”. Clearly, there will be push back from the AFM if information requests are seen as being too onerous or costly.

Subjectiveness: “Value” is subjective and open to interpretation. In the US, it is possible that “value” be declared by the Fund Board, even though performance or other evaluation criteria come out as “Poor”.

For a Fund Board, making that final decision may be challenging. For example, will Fund Boards consider fund performance over the last year, rolling RHP periods or over the course of the economic cycle? There may be a bonafide reason as to why to consider one approach for one given AoV principle and another approach for the others. However, a piecemeal de-coupling of the approach could be risky and akin to cherry picking.

Measuring the “value” component of performance for funds that do not use benchmarks may prove to be difficult as there simply is no benchmark return to compare against, either on a gross or net of fees basis. If a fund does not use a benchmark, then the AFM must inform investors on how to assess the performance of that fund. The FCA has just introduced new rules (PS17/28) on this subject which will be in place by the 7th of May for new funds and by the 7th of August for existing funds.

Where possible, Fund Boards should remove the subjectivity element from the decision-making process by making full use of any available external comparator in defining “value”. Having evidence as to “value” from independent third parties, such as the Pension Policy Institute, the Financial Ombudsman Service or consumer trust-based organisations, such as Trustpilot, might prove to be of considerable help. Arguably, the winning of any industry awards that a fund or AFM has recently won may also point to “value”.

Economies Of Scale: Whether or not economies of scale are identified and achievable; the AoV regulation allows for them not to be passed on to investors should justification be found for retaining the money to invest in certain fund “improvements”, such as an improvement in the fund’s infrastructure.

The more experienced investor might argue that investor cash should not be used to pay for fund or AFM infrastructure as that is paid for already out of the fund’s Annual Management Charge (AMC). Is the explanation for not passing on economies of scale to investors a valid one? Some savvy investors might challenge this reasoning.

We have mentioned the formulation and use of a number of KPIs to inform and drive solid decision making at Fund Board level. Whilst the AoV regulations target the share class level, a review of economies of scale will need to consider the entire fund complex. Close examination of the cost and revenue allocation methodology used by the AFM to allocate costs from the AFM to the fund and from the fund to all share classes may prove illuminating.

Any mechanism used to allocate costs and revenue in instances whereby one in-house fund invests in another in-house fund should also be reviewed. Fund Boards may want to validate whether or not the cost and revenue allocation mechanism is fair to all, including the AFM. For any given fund, there will be a relationship between profitability and costs as fund AUM increases. The Fund Board will have to decide how to interpret the findings and then decide whether any excess profitability is due to economies of scale that have not been passed on to the investor.

Accounting practices may vary, either by fund or by AFM, as to how different costs are calculated and then charged to the AFM or the fund. The focus of the AoV regulation is, first and foremost, investor outcomes and not the commerciality of the AFM. That said, if the AFM is not making a profit then inter alia this may mitigate the fact that charges are not unreasonable, unless performance is exceptionally poor, of course.

One obvious difficulty here is when the AFM itself is generating an operating loss, and the fund is generating a profit. This can be especially true for start-up AFMs and for smaller asset management boutiques. It would seem unfair to bestow the AFM some sort of ‘AoV’ uplift (i.e. an increase in “value)” against cost simply because the AFM is losing money.

Indeed, in some instances, the firm might be justified in raising fee levels to reach profitability. This, however, should not provide a “get-out-of-jail” card for AFMs that calculate P&L net of director remuneration. The fee structure adopted by the fund here would also have a bearing4 – be it; flat AMC, performance fee, fulcrum or symmetrical AMC etc.

If an AFM is then operating a ‘supertanker fund’, we note that there is no independent statistical or academic support to suggest that these funds benefit from a performance advantage by virtue of size alone. Indeed, contemporary APFI studies suggest the opposite, that diseconomies may arise especially once liquidity risk is considered. How building scale is then justified against investor outcomes may prove to be a tricky issue to resolve, which is why we call for the Maximum Fund Size metric to be available on fund documents at both pre-trade and at post-trade on the AoV investor disclosure.

The Maximum Fund Size metric would be an indicator of the fund AUM scale point, at which, implementing the fund’s investment decisions in the market starts to incur noticeable frictional costs, with the obvious impact on performance. This is a good indicator for “hot” funds that quickly attract increasing levels of AUM after recent strong performance. To be clear, AFMs should be allowed to increase the Maximum Fund Size but should clearly articulate their reasoning and clearly include any changes to their investment process and implementation process that would allow them to cater for the additional scale.

The Market Test: Prices And Service Levels: As US attorney Jerome Schlichter has successfully found in the US, many pension fund trustees have not been keeping an eye on market prices and service levels for both internally and externally provided services.

Under the FCA’s regulations, UK Fund Boards will have to periodically test the market for all services to ensure that they are competitively priced and that the service level is as contracted.

Given that we advocate using the rolling RHP period as the frequency for investors to measure “value” in a fund (we cover this later in the section entitled “An Investor’s Perspective of “Value””), it stands that AFMs should also be allowed to test the market for all services once per rolling RHP period. Should the fund RHP period prove to be shorter than 5 years, then a statement as to market test policy and frequency should suffice. Fund Boards will need to carefully consider how they would operate and evidence a market “test” as it can take precious amounts of time and could prove to be costly. Fund Boards should also be cognisant of the fact that a market “test” is not the same as an actual commercially-driven service provider selection exercise – results may differ markedly.

The Fund Board may have to seek out the services of a specialist professional firm (or firms) to help them determine the market rate for each service supplied to the fund. Any professional firm employed for this purpose should operate on an arm’s length basis and should, ideally, be completely independent of the AFM, the fund and all of the fund’s service providers.

The second Gartenberg principle states that the compensation received by other advisers (ergo AFMs) under similar circumstances had no bearing on the reasonableness of another as not being “arm’s length”. The rule here is quite simple: being wrong together does not equate to being right.

What happens should a Fund Board find that a service supplied to the fund is overly expensive, is of poor quality or does not meet contractual obligations? Can the cost and service level be corrected easily and with minimal cost? It might well be worth spending the time to put things right as the costs of switching provider might prove to be prohibitive. And going ahead with a change of provider may only stack more costs onto the fund for next year’s AoV process.

Nonetheless, the pressure on fund management margins isn’t going to go away and, as a consequence, we also see margins falling for those who supply services to the industry. The market is rebalancing and will continue to do so for a while until a new equilibrium point is reached.

Share Class Equality: The range and quality of service provided to different types of unit-holders may be quite disparate. Commercially aware institutional investors will play hardball on the advertised costs, whilst demanding tailored reporting solutions for performance and risk purposes, for example. Some may even demand a list of up-to-date fund holdings and the ability to load all data into their own systems on an ongoing periodic basis. Institutional service quality is generally extremely good.

Retail investors, on the other hand, generally pay more than institutional investors, sometimes 2 to 3 times more, yet have little or no bargaining power when it comes to commercial arrangements or obtaining extra services. As a retail fund investor, even trying to obtain a spreadsheet of gross and net returns might be too much to ask for the AFM.

It could be argued that the presence of many retail investors in a fund, all with relatively small holdings, means that end-to-end processing costs might be quite high - but it is not that simple. An analysis at share class level of the services provided, revenues, costs and profit margin will furnish Fund Boards with valuable insights into the “value” generated for each type of investor.

We note the existence of “platform” and “internal” share classes in annual reports and other fund documents that have no visible charges or low charges when compared to the fund’s other share classes. Platform share classes may reflect a distribution agreement with a given retail or other investment platform, such as Hargreaves Lansdown. Internal share classes, on the other hand, may allow for investors, who are invested in other funds managed by the same AFM, to enter a fund without having to pay two sets of annual management charges.

The share class concerned may have a zero advertised cost, but that is not to say that management fees are not debited from fund one and then credited to fund 2 via another mechanism. The point is that there is a lack of transparency here on the costs and the services provided to a fund and Fund Boards and iNEDs will have to ensure an equal and fair playing field for all unit-holders.

Should an institutional investor invest via a segregated mandate (i.e. a separate, segregated portfolio that mirrors the investment strategy of the fund), then comparing fees on an “apples with apples” basis might be quite difficult. Fund investors will use all the fund’s infrastructure, including the AFM, the custodian and countless other counterparties who provide a myriad of services.

An investor using a segregated mandate pays for the management of the portfolio and a few other services. The segregated mandates will likely have their own custodians and numerous counterparties – and will pay for them separately out of their own money. This is reflected in the lower AMC paid to the AFM. Evaluating charges and services for some types of client, such as those who invest via segregated mandates, will, therefore, require detailed service and cost data.

Peer Fund Groups: One way of pointing to “value” is to compare the fund against other similar funds or peers. We note that it is possible to define a peer fund group in many different ways. It could be a list of those funds that the AFM considers close competitors; it could be a list based on the fund category of any one fund data provider (i.e. the IA Sector, Lipper or Morningstar); or it could be a “mapped” peer group whereby a set of rules are applied to a fund category to pick out those funds that most closely match the fund (for example, those funds with identical or near identical investment objectives).

In the US, some Fund Boards review net performance against peer funds and other relevant indices. Whatever the peer fund group, it should provide for a meaningful comparison.

We note one example from a Gartenberg disclosure that reports on fund v peer group performance positioning using the “mean” instead of “average”. This raises the question of what happens if the US investment adviser modelled the peer group outcomes using both mean and average and found that using the mean gives a better result for the fund. If so, then that is very probably cherry picking, unless it is used consistently across an AFM’s entire product stable on an ongoing basis.

Metrics, Metrics And More Metrics: Interestingly, in Q4 last year, the CFA Society UK published a report entitled “Value For Money - A Framework for Assessment” which outlined a possible “strawman” framework for assessing Value for Money for Fund Boards.

We believe that the framework outlined here could guide Fund Boards and/or be adopted in full or in parts for the Assessment of Value tests and disclosures.

A few of the metrics advocated for use in the CFA Report will enhance the investor “value” experience, but others may contradict existing regulatory metrics or may not be widely known to investors. Either way, whatever metrics are used, they should all appear in fund documentation both at the time of trade and in the AoV disclosure to allow for a fair and meaningful comparison for “value” determination purposes.

Some types of fund documentation, such as the Fund Prospectus and Key Investor Information Document or Key Information Document (KIID/KID) are highly regulated in terms of pre-mandated content and document length. Other types of fund documentation, such as the fund Factsheet, are less well regulated, so often contain much more information than the KIID or KID. Many of the metrics referenced in the CFA Report are not regulatory per se, so should appear in the fund Factsheet if used in the AoV investor disclosure.

The more measures used, the more technically adept the reader needs to be to extract “value” from them.Whilst we comment on some metrics that could appear in the investor’s AoV disclosure below it should be noted that the following is not an exhaustive list;

- CSO (Client’s Share of Outperformance): Not widely reported in fund documents or as part of the investment process for the majority of investors. This is a new metric as far as fund disclosures are concerned and it may unintentionally confuse investors as they won’t be conversant with it.

- OCR (Ongoing Charge Rate): Advocated as an alternative cost metric for use in AoV investor disclosures. We don’t think that investors will have heard of this cost metric before at all. It is also likely to report lower costs than the UCITS OCF or MiFID II OCF used at time of purchase.

- Triangulation: Involves triangulating a range of metrics for comparison purposes. A triangulation performance comparison involving the fund against the benchmark (if it has one), the fund’s peer group and a low-cost passive alternative could be extremely helpful with respect to showing relative value across similar products.

- Reverse order reporting of performance: In terms of the return aspect, we believe there are some simple approaches that can foster long-termism which will benefit the investor, industry and the economy. We would advocate reporting and evaluating performance returns in backward order, starting with ‘Since Inception’ then 10 year, 5 year and so on.

- “Active Cost” metrics: Advocated by some industry players, like Mercer. Active Cost has a number of limitations and crucially misses the point on friction.

- Volatility: The UCITS SRRI (Synthetic Risk and Reward Indicator) and MiFID II SRI (Summary Risk Indicator) are calculated via a volatility-based prescriptive calculation methodology and must be displayed on the UCITS KIID, MiFID II KID and the PRIIPs KID, as appropriate.

- Sharpe Ratio: A universally accepted metric, endorsed by the EU, which might be of use to the AoV process, especially when applied to funds that are volatility rated. Not particularly intuitive for retail investors to follow.

- Information Ratio: Sometimes referred to as the ‘Manager’ or ‘skill’ ratio. This metric might be of use to the more sophisticated investor but possibly not retail. Information Ratios can be calculated broadly in three different ways and are sensitive to benchmark error. They could also be open to manipulation unless documented in detail.

- Value at Risk (VaR): VaR will likely be an input for many Fund Boards but is sensitive to time period (assuming use of the RHP) whilst noting that VaR becomes less accurate over longer time periods. Not particularly intuitive to some types of investor.

The Reporting Of Costs: Assuming that costs will be reported in the AoV investor disclosure, MiFID II and PRIIPs take the approach of mandating that costs be reported via an actual monetary figure (in £ for UK investors) together with a percentage figure on the Key Information Document (KID). In a pooled vehicle, with varying different amounts invested by clients - possibly at different times, it may appear more intuitive to consider that cost in % terms, especially if being compared to performance returns.

Whether or not AFMs choose to report costs as part of their AoV process is another matter, but cost reporting is reasonably well covered by the MiFID II and PRIIPs regulations. It is understandable should AFMs not want to duplicate this function, even though costs are a significant factor in determining “value”.

II. The Forest Of Uneven Regulation And Regulatory Metrics

The regulatory environment is voluminous and complex. Really complex, in fact, and there are unseen political considerations that could impact anything at very short notice.

A firestorm of regulation has hit the EU financial services market since the Credit Crunch of 2008, and there is still no end in sight. Regulatory initiatives will, therefore, continue to directly impact the AoV process.

MiFID II & PRIIPs: MiFID II went live throughout the EU on the 3rd of January 2018. At the time of writing, 9 EU nations still haven’t yet transcribed these rules into law and most nations are still implementing. The UK is not yet compliant, we think, but it is close. Regulators across the EU are, however, not enforcing their own rules and we note that some fund management and investment platform websites are either putting up multiple cost disclosures for funds (each showing a different total cost) or are putting up an older incorrect cost disclosure.

Exactly where this leaves the AFM and the Fund Board is a difficult question, but erring on the side of caution and playing it safe by publishing the correct legal cost disclosure is the route to follow. Not following the law because the regulator isn’t enforcing won’t be a solid defence in front of a judge should an investor initiate legal action. Using an older cost disclosure that reports lower fund costs for the purposes of the AoV process will lead to an incorrect declaration of “value”.

UK Authorised Funds should currently be reporting costs per the MiFID II regulations, although some might be governed by a transitionary regime under UCITS. It is confusing as there are two similar, but different, regulatory regimes in force at the same time. UCITS uses a pre-mandated Key Investor Information Document (KIID) to provide essential fund metrics to the investor, with costs, also subject to a strict calculation methodology, being reported per the UCITS Ongoing Charges Figure (OCF). MiFID II essentially seeks to boost cost transparency beyond UCITS and uses the same pre-mandated approach with respect to the MiFID II Key Information Document (KID) and the MiFID II cost metric, the MiFID Ongoing Costs Figure (OCF).

But let’s not get too comfortable, another set of forthcoming EU regulations for pooled funds, PRIIPs, builds on MiFID II cost disclosures via a pre-mandated Key Information Document (KID) and another cost metric, the Reduction in Yield (RIY). The PRIIPs RIY will be the fullest available cost metric in the market when it comes to reported costs and will need to be used to compare “value” as part of the AoV process once it is introduced. Until that time, the AoV process will need to use the MiFID II OCF.

PRIIPs was introduced for investment companies in January 2018 and the resultant problems were widely reported in the press. Costs aside, there were major issues with the pre-mandated calculations for risk and performance that are required to be reported on the PRIIPs KID. Some investment companies came out as being far less risky than they actually were and investors ran the risk of being misled. As a result, the EU are reviewing the regulations with a view to making changes to PRIIPs and the implementation date for pooled funds is looking to have slipped from January 2020 to January 2021.

Fund Boards will have to consider whether or not full investment costs are being reported when identifying “value”. They will also have to ensure that their AoV framework is flexible enough to support the regulatory changes that are coming through in the next year or two.

FCA Discussion Paper (DP18/5) “A Duty of Care and Potential Alternative Approaches”: iNEDs should be aware of this forthcoming FCA Discussion Paper and what it proposes. The discussion paper gold-plates certain duties, which if breached, might open the door to fund litigation in the UK.

The US and the TER Cost Metric: It is important to note that the regulatory regimes in the US and EU (UK) are completely different, with the EU having a higher level of investment cost transparency than the US.

The Total Expense Ratio (TER) cost metric, currently in use in the US and reported in investors Gartenberg disclosures, was abandoned in the EU over 5 years ago in favour of a metric called the UCITS Ongoing Charges Figure (OCF). The UCITS OCF provides for fuller cost disclosure than the TER.

To highlight the shortcomings in the TER, we don’t think that Fidelity’s “zero-expense” (or zero TER) mutual funds would come out with zero costs on a MiFID II KID or a PRIIPs KID.

The use of a lower cost metric, such as the TER, to assess the cost component of “value” presents investors with a form of cost arbitrage: Gartenberg applies that lower cost hurdle (i.e. the TER) with more subjective measures to create a legal defence against ‘excessive fees’. Why use a cost metric then that under-reports the true level of fees whilst at the same time artificially inflating “value”? That’s a rhetorical question by the way. Should Fund Boards have any doubt as to which cost metric to use, they would do well to source the costs for the fund using all cost metrics that may be in use. The cost component of “value” should then be assessed using the cost metric with the highest quoted cost figure.

Our starting assumption here is that the cost used to calculate net performance will impact any hurdle or benchmark comparison that inputs into the AoV process. Importantly, there is no indication from the FCA that they intended for anything other than the legally correct cost metric to be adopted to drive the AoV process.

Missing Costs: No “Assessment of Value” or “Value for Money” measurement exercise can be completed until all of the main driving principles have been firmly bottomed out, otherwise it may invite an incorrect result. We are uncertain as to whether the current and forthcoming regulatory cost metrics pick up all costs. In fact, we think it unlikely. So how will “value” be determined when fund costs might not be complete?

Another important cost question arises when deciding what items should and should not be charged to funds. Cost items, such as investment research, are arguably part of the day-to-day cost of doing business for the AFM and should be paid for out of the AMC.

Pre-MiFID II, investment research was, in the main, traditionally paid for via soft commissions on trade flow, which was not necessarily fully visible to the investor who was paying for it. So, what happens with other similar cost items, such as fund marketing fees, distribution fees and the costs of launching new share classes? All are charged to the fund, but arguably, don’t benefit the end fund investor.

We appreciate the fact that many of our readers may not agree here, but it does raise the question of price discovery for investors. Every consumer needs to know the true initial and true ongoing cost of a product or service - and nobody can determine “value” until that has been achieved.

III. The Difficulties In Benchmarking AoV Principles & Costs

Looking to other approaches might help. A directly relevant and similar regulatory exercise to the Assessment of Value was carried out by the regulator, the FCA, in April 2015 acting on a unilateral basis in the local UK market.

The “Value for Money” Experience: The FCA acted after the Office of Fair Trading conducted a market study of Workplace Pension schemes in 2013 and found competition problems and conflicts of interest. As part of the remedies, Independent Governance Committees (IGCs) were set up to oversee each Workplace Pension arrangement with every IGC having to produce an annual “Value for Money” (VfM) statement.

The IGC was mandated to act solely in the interests of relevant scheme members and to act independently of the Workplace Pension provider. The majority of IGC members must be independent, which is similar to US Fund Boards under Gartenberg, but is not a requirement that has not been applied to UK Fund Boards for Assessment of Value purposes.

The IGCs’ experience of producing their annual VfM statement will be helpful for Fund Boards looking at “value” frameworks. Our observations of the VfM process at the time include;

I. In the first set of c.18 annual IGC Reports, issued in 2017, the IGCs used a total of 23 different VfM principles to help determine “value”. Some IGCs used under 10 VfM principles, whilst others thought it appropriate to use over 20. Some IGCs applied confusing layers of VfM principles, with the first layer being a small number of Driving or Governing Principles, followed by the VfM principles themselves and further sub-principles.

II. For the purposes of assessing value, IGCs, like Fund Boards under the AoV regulation, are free to define and use as many principles as they see fit.

III. For the annual IGC VfM statement, no specific VfM principles, metrics or reporting format was advocated by the regulator. It was left entirely open, as arguably, “value” is subjective, and each Workplace Pension is different – as is the Workplace Pension member’s experience.

IV. IGCs also used many differing cost metrics to report costs (over 6, in fact), meaning that any Workplace Pension member with two pensions from different providers could not really compare them. Many of the cost metrics reported were simply not fit for purpose – some were even proprietary. But let’s not forget that insurance-related financial products operate in a different regulatory environment and at a slower regulatory speed than the AFM space.

V. Consequently, industry efforts to provide some kind of IGC Workplace Pensions benchmarking proved frustrating, if not impossible. To this day, we are not sure if any successful benchmarking was ever carried out.

VI. Some initial research carried out in conjunction with 11 IGCs pointed to “perceptions of what value for money means focus around good returns”. Two further key findings were that “charges are not front of mind and are not in the top 10 attributes for the majority of members” and that members placed a “strong emphasis on the importance of trust and protection”.

VII. Some IGCs did come up with some unusual, but extremely useful ways of evaluating VfM principles. The Phoenix Life IGC in their Annual Report used external bodies, such as the Pension Policy Institute (PPI) and the Financial Ombudsman Service (FOS), as comparators to provide an independent validation of service levels, complaints, complaints resolution and other factors. A good example was their use of the FOS “overturn rate” which measures how often FOS disagrees with a financial services company’s decision on an investor complaint.

VIII. The third set of IGC reports were published in H1 2018 and commentators noted that they are “as diverse as ever”. Unless there is a harmonisation of the VfM requirements by the ABI or FCA (we think that is unlikely) and then a reconciliation back to the AoV, then the continual industry occurrence of slipping between both terms to describe either is unhelpful.

However, let’s not lose sight of the fact that the direction of travel with IGCs and Workplace Pensions has been positive. And that is exactly what the regulator wanted. The strategy behind the new AoV rules for AFMs are similarly well placed, even if they could be undermined by different tactics.

In summary, we believe that there is a strong possibility that the Fund Board AoV journey could mirror that taken by the IGCs in their quest to identify VfM.

IV. An Investor’s Perspective Of “Value”

Whilst the UK consumer might be ranked at number 2 in the world when it comes to financial literacy, evidence points to the many who can become quickly disengaged with their finances. Any new disclosure regimes, therefore, must be consistent and easy to understand.

The FCA has not specified the format or content for the end AoV investor disclosure, and this, we believe, allows considerable room for manoeuvre when determining “value”.

An Investor’s Investment Process: Investors buy financial products to accomplish a myriad of different financial aims, whether it be for pensions, for life-time savings or for another purpose at some set future date, such as a child’s 18th birthday.

Every investor will have their own investment process that they will follow to achieve their investment aims. The investment process followed then may well be simplistic, in the case of a retail investor, or could be more sophisticated, in the case of an institutional investor. For some though, it may even come down to the colour and design of the fund documents.

An investor will typically identify their risk level and, therefore, the asset class before moving on to identify some specific fund products that, at first glance, could fit the investment purpose. The investor will then, in all likelihood, delve deeper into the specific T&Cs of the products in the fund documentation with a view to whittling them down to one or more products.

Therein factors such as those listed below become invaluable when deciding which fund to buy and determining how it might generate “value” over time for the investor concerned;

- Asset allocation

- Net potential returns v benchmark

- Initial and ongoing annual costs

- Risk (SRRI/SRI)

- Past performance (net and gross of fees v benchmark)

- The size of the fund

- Maximum Fund Size

- The AFM’s credentials and other related-factors

- The Recommended Holding Period (RHP)

Consistency Of Data And Metrics Used At Time Of Sale vs.Those Used In The APV: To drive cost transparency and to provide a level playing field across fund products in Europe, cost, performance and risk metrics reported in fund documentation are heavily regulated and can only be calculated via a small number of pre-specified and mandatory calculation methodologies. These various metrics, together with other information in the fund documents provide for the conditions in which fund products are sold by fund management firms and bought by investors across the EU. They are there to protect the investor and allow them to gauge potential “value” between similar products at time of purchase.

The point at which “value” should start to be measured is as at the time of purchase and the regulatory and other metrics, that were consumed at time of purchase, should form the basis on which to measure “value”. This is what the investor used to determine their expectations - and “value” cannot be measured consistently and transparently once different metrics and information are reported later post-purchase on the investor disclosure. In fact, new metrics and information are likely to increase inconsistencies and asymmetries unless consistently applied.

Investor Disclosures: We note that some investment advisers in the US have chosen two approaches when it comes to the Gartenberg investor disclosure. The first being a dedicated fund-specific disclosure (i.e. one per fund). The second takes a partially “combined” approach whereby a small number of shared AoV findings, such as the quality and range of centrally supplied services, are reported across the fund stable and findings specific to the fund are reported in the investor disclosure itself. We believe that all findings should be in one document to encourage ease of use and better investor engagement.

Evidence in the US suggests that the many differing Gartenberg investor disclosure formats in use amongst fund management groups have converged over time, thereby allowing investors to compare the “value” in funds across different fund ranges. We don’t think that such a Darwinian approach, played out over years, is in the best interests of the investor or the industry. In this respect, will the AoV investor disclosure be “fair, clear and not misleading”?

Gartenberg reporting to investors in the US amounts to little more than a brief statement buried deep in the shareholder report. By comparison the AoV investor disclosure in the UK will be firmly in the public domain and it is this disclosure that will clearly define the AoV itself. Fund Boards will have to give careful consideration to how the AoV findings are reported and communicated and, importantly, to how investor expectations are going to be managed.

In addition, the use of new or other metrics, that were not seen by the investor at time of purchase, should be used only to supplement any deeper analysis; rather than deviate from the customer perspective. Ideally, the exact same metrics and data used at time of purchase should also be available in the AoV investor disclosure - and vice versa5.

The Importance of Time and the Recommended Holding Period: How “value” is disclosed is crucial and the way a fund generates “value” is sensitive to the holding period it is measured against. “Value” has an inescapable time component. Contemporary studies, such as those relating to the Fidelity Magellan Fund, captured how investor outcomes vary greatly depending on buy and sell behaviour and the investor holding period.

The problem for pooled vehicles is that they are the collective of thousands of different investors, all potentially with different holding periods. Worst still, AFMs don’t know as much as they would like about those who are invested due to the presence of distributors, nominee companies and omnibus accounts. Therefore, the Recommended Holding Period (RHP) becomes a yardstick for the Assessment of Value against a holding time period recommended by the AFM to investors, so that they achieve their expected investment objectives from holding that particular fund. However, as the RHP is standardised, then it can only be approximate for any given investor. It is, nonetheless, an important yardstick.

For an investor then, the RHP is clearly stated on the heavily regulated fund Key Investor Information Document or Key Information Document, as appropriate. The RHP starts the day that the investor purchased the product. The AFM, as product manufacturer, uses the RHP, per the regulations, to explain, in terms of risk, why that particular RHP has been chosen and how factors such as early-redemption, early exit penalties (sometimes referred to as Contingent Deferred Service Charge or ‘CDSC’) and capital guarantees may be impacted should the fund be sold within the RHP.

The older UCITS regime, the current MiFID II regime and the forthcoming PRIIPs regime all stipulate that an RHP be reported on the KIID or KID. Imagine our surprise then when we found out that there are three versions of the RHP out there - one version for each of the three regulatory regimes – and they are all different.

The UCITS regulations do not require any explicit statement of the investment horizon or RHP, instead allowing the “Investment Policy” section of the UCITS KIID to capture the RHP in a simple narrative. MiFID II takes a different approach and mandates the use of textual values to specify the RHP. A MiFID II KID uses terms such as “Very Short”, “Short”, “Medium” and “Long” to describe how long an investment should be held for. PRIIPs, however, is more precise and requires an exact number, in years, to be clearly visible. Depending on which regulatory regime applies to the fund, fund management firms are then faced with having to map these RHP values into one PRIIPs RHP number.

The importance of the RHP, a purely standalone figure in the UCITS and MiFID II regulations, increases under PRIIPs because now it drives some of the pre-mandated calculations on the PRIIPs KID. This includes the Market Risk Measure (MRM) and the Credit Risk Measure (CRM). It is also used to drive the time periods for which fund performance and the “RIY” costs are to be displayed. For a fund with an RHP of 5 years, an investor will see performance and costs as at 1 year, 3 years and 5 years (5 years here is deemed long-term). Interestingly, this differs with the definition of ‘long-term’ suggested by the CFA and pension providers which atypically infers a holding period of 5-10 years or more.

One further point of importance is that many funds may have inadvertently changed their RHP to a longer 5-year period as part of the current PRIIPs implementation. Fund Boards and iNEDs may want to check whether or not the RHP is correct. Any error could simply be down to the fact that an incorrect 5-year default value was applied when fund management firms completed their PRIIPs data templates.

The Investor’s RHP Conundrum: We said earlier that the RHP starts the day that the investor purchased their Authorised Fund product. An investor who purchased an Authorised Fund with a 5-year RHP on the 1st, January 2015 to meet an investment objective will be looking to exit in January 2020 or at the very least will rightly be expected to be looking hard at their valuation statement.

Different types of funds have different RHPs to accommodate the investor’s investment objective. Some funds, such as cash funds, may have a 1 year or less RHP. Other funds, such as pension lifestyle funds, might have an RHP as short as 2 years or as long as 15 years or more. We note that some funds with shorter RHPs do not state the RHP on the KIID/KID. We are not entirely sure why, but ask how investors will measure “value” for these funds?

On receipt of their first AoV investor disclosure, an investor might well ask if it covers the last single financial year or rolling RHP periods – for example rolling 5-year periods. Thus, measuring “value” against any period other than the rolling RHP period may undermine the investor’s view of “value”.

For example, in the US the Fidelity Fund Board considered the investors’ expected holding period in their Gartenberg disclosures; “The Independent Trustees recognize that shareholders evaluate performance on a net basis over their own holding periods, for which one-, three-, and five-year periods are often used as a proxy”6.

Should the AoV disclosure only be back-dated to cover the fund’s last financial year, then does this mean that this particular investor can only measure “value” upon receipt of the 5th AoV disclosure in 2024? The original RHP that they bought the fund on would end in January 2020 – that is a long 4 year extension to the original RHP.

Additionally, what happens if the AoV changes annually for the first 2-3 years due to regulatory and/or other changes – does this mean that the AoV disclosure is subject to reset risk, at least for an initial period? If so, when can the investor start to measure “value” consistently from? Consistency is key.

Conclusion

We expect that Fund Boards will still find lots of room for manoeuvring when producing the AoV investor disclosure. Full and proper consideration of the customer’s viewpoint when making all decisions should ensure alignment and de-risk the process. The Fund Board will consider if there are any additional or mitigating factors to adjust for. However, the temptation to de-couple the AoV investor disclosures from the metrics used at time of purchase should be avoided.

With this in mind, incoming iNEDs will be tasked unequivocally to be ‘independent’. They will be given access to sensitive internal information to assess but in many ways their questions will not be that different to a Professional Fund Investor. Nonetheless, we firmly believe that no conclusive view on “value” can be made on publication of the first AoV investor disclosure. Fund Boards will be getting to grips with “what they have” and trying to bottom it all out. Their binoculars will be firmly focused on what the market is doing and how peer funds compare.

A number of fund management groups, Fidelity included, have recently announced that they are looking at reducing their fund ranges, some by up to 25%. Unprofitable and or poorly performing funds will probably be top of the list and we expect this trend to accelerate post the advent of the AoV regime. Reviewing under pressure funds now, however, negates the need to make tough decisions that a Fund Board might have to make in public come September.

We recognise that the US “Gartenberg” regime took many years to settle in, with positive change occurring over the long-term and not overnight. Commercial businesses need time to adopt to a sea-change in regulation, transparency and culture. More ‘Bootcamps’ are needed.

Professional Fund Investors, in turn, will rightly query AFM progress through their due diligence when they ask;

‘How robust is your Maginot Line?’”

If you found this paper useful, then look out for our next paper on Assessment of Value entitled “The Art of ‘Value’ - iNEDs in the Boardroom”.

Notes

[1] Sources: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maginot_Line

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Maginot-Line

[2] “We estimate that over three-quarters of the UK population are exposed to the asset management sector, either directly or through their pensions. It is important that competition works well in this market as, for example, even small differences in the charges they pay can have a significant impact on people’s savings over time”.

FCA Business Plan 2018/2019

[3] https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/investment-costs-europe-game-thrones-sunil-chadda-jb-beckett-chadda/

[4] “Following our Asset Management Market Study, we will monitor the market to assess how outcomes are changing in this sector. Relevant information will include measures of price clustering and whether firms are passing on gains from economies of scale to their customers”.

FCA Business Plan 2018/2019

[5] “It is crucial that firms’ decision-making gives due prominence to customers’ interests”.

FCA Business Plan 2018/2019

[6] Fidelity Contrafund – 15C Fund Board Statement, Annual Report, December 21, 2017.

Further Reading

Investment Association paper

https://www.theinvestmentassociation.org/investment-industry-information/research-and-publications/

CFA Paper

Gartenberg links

https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/FSupp/487/999/2125405/

Phoenix Life IGC Annual Report 2016

Citywire article on Fund Boards - JB

UK Fund Board iNED Bootcamp slides

The Association of Professional Fund Investors (APFI)

FCA Discussion Paper (DP18/5): “A duty of care and potential alternative approaches”

FCA Asset Management Market Study (AMMS)