Some Misconceptions, Speculations and Inconvenient Truths

Wednesday, 14 May 2014By Con Keating

Even though the paradox of thrift has been known since biblical times[1], one of the few points of overwhelming agreement at the initial meeting of Mallowstreet’s Partnership for Change was that increased household savings should be a central objective of pension policy and practice. As the ambition of the Partnership for Change is the sustainable development of long-term savings, this should not be surprising, though it is disappointing. Unfortunately, it was merely the first of a number of misconceptions evident that day.

Although the paradox of thrift is usually attributed to Keynes in the 1930s[2], John Robertson’s 1892 book, The Fallacy of Saving observes:

“Had the whole population been alike bent on saving, the total saved would positively have been much less, inasmuch as (other tendencies remaining the same) industrial paralysis would have been reached sooner or oftener, profits would be less, interest much lower, and earnings smaller and more precarious. This ...is no idle paradox, but the strictest economic truth.”

In the simplest of terms, it is no more than the observation that savings arise as the residual difference between income and consumption. If we wish to increase savings, this comes at the expense of consumption. If we increase savings, we are consuming less current production while increasing the capital available to productive activities – in this circumstance the returns available to suppliers of capital will fall, as there is both extra supply and lower demand.

That day the terms savings, wealth and investment might have been, unhelpfully, interchangeable. Keynes[3] helps in this regard:

“...mere abstinence is not enough by itself to build cities or drain fens. ...Thrift may be the handmaiden of Enterprise. But equally she may not. And, perhaps even usually she is not.”

A quotation from GLS Shackle is appropriate: “In a world where savings and investment are divorced from each other by money, the inducement to invest must be separately studied.”

The critical question is the form of the investments made with these savings. This is true in terms of the expectations and outcomes for both the investor and the economy at large.

One behavioural point is worth noting – scheme members regard their contributions as savings rather than investments and regard losses on savings as unacceptable. This is often interpreted as risk aversion on the part of these individuals.

In result, these savers will often simply default to savings deposits in the banking system. If we look at the uses of funds by our banks, an INET analysis for 2009 attributes just 12% to productive corporate investment, while commercial real estate lending which is a mixture of productive investment and leveraged asset plays accounts for 12.5%. Residential mortgage lending, which is in large part just the refinancing of existing assets, with a little productive new build, amounts to nearly 64% and unsecured consumer finance amounts to nearly 12%. By far the largest volume of bank lending is financing life cycle consumption smoothing, rather than productive investment.

Though consumer debt is much demonised it is as much a valid form of life cycle consumption smoothing as its opposite form saving. The difference between the two is that indebted consumers will be paying part of their income to those who have saved, aggravating wealth and income inequalities – this is trickle up rather than the trickle-down that proved illusory in the 1980s. As most mortgage finance is concerned with the purchase of existing assets, it is worth illustrating the level of investment, and its constituents.

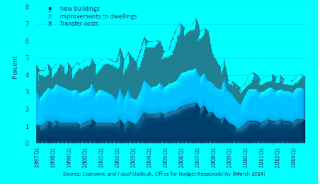

Figure 1: Residential property investment as proportion of GDP ( 1997 – 2013)

The OECD has associated three attributes to long-term investment; this is patient, productive and engaged capital. There are some important differences here – productive investment will tend to increase the total level of output; it increases the size of the overall pie. While consumer finance merely redistributes it. It is natural that the demand for investment should have a term that is longer than the term of savings as most of these are not long-term in nature, merely precautionary. Intermediation of this temporal mismatch is one of the more important economic functions of the banking system. Many other financial institutions have been created to resolve this maturity mismatch issue while operating in the capital markets. This extends beyond institutions that operate as principal, such as insurance companies, and includes entities such as mutual funds. In other words, liquid capital markets also fulfil a transformational role.

The decline in capital expenditure (capex) was again cited as evidence of a savings issue, but without regard to the fact that the prices of capital goods have declined. In 1980, UK capex was 12% of GDP, and has declined to 8% in recent times, but when adjusted for the relative prices of these goods is still 12%. This is another side of the argument that we can’t afford pensions or health care, and shows a lack of understanding of the effects of productivity. It is clear that,under conditions of economic growth, we can afford more of everything in the future, including pensions, but for many reasons, including demographics, we should expect growth to be lower than we experienced in the post-WWII world.

However, the argument for affordability is not predicated on growth, but merely on differences in the relative rates of productivity growth in different sectors of our economy. A simple extrapolation of past productivity and costs from 2005 to 2105, by William Baumol[4] shows that health care costs can rise from the 15% of GDP in the base year to 62% in 2105. What matters is not how fast productivity increases in the health-care industry, but rather how fast it rises in all others. In Baumol’s words, “We can afford it all”, as history has shown us; there is no need for any decline in either quantity or quality.

As society ages we should also expect a shift in the patterns of consumption: pensioners do not need another refrigerator or mobile phone, but they will need extra care and health services. The important issues lying ahead of us are in distribution not in absolute or relative level.

No pension conference would be complete without the demographic dependency ratio being trotted out as evidence of an impending crisis, and this fails to take into account that it is the economic dependency ratio that matters. The demographic dependency ratio is the number of pensioners divided by the number of people of working age. It includes in its denominator those not working. The economic dependency ratio considers all dependents, including children, and just those working. The economic dependency ratio was higher in the early 1980s, when unemployment was high and output depressed, than it is now projected to be. In addition, we should expect higher female labour force participation. The physical capacity arguments of the 1950s are now entirely irrelevant; in a knowledge economy, their higher levels of tertiary education and qualification will count.

The most overlooked aspect of the “demographic time bomb” is that the smaller relative size of the workforce can be expected to demand a larger share of national income as wages at the expense of capital. The trend over the past forty years for the share of national income captured by capital to increase can be expected to stop or reverse[5]. The higher relative wages will encourage those who are economically inactive to join the labour force, while it also raises questions over the future returns achievable by from today’s capital investments.

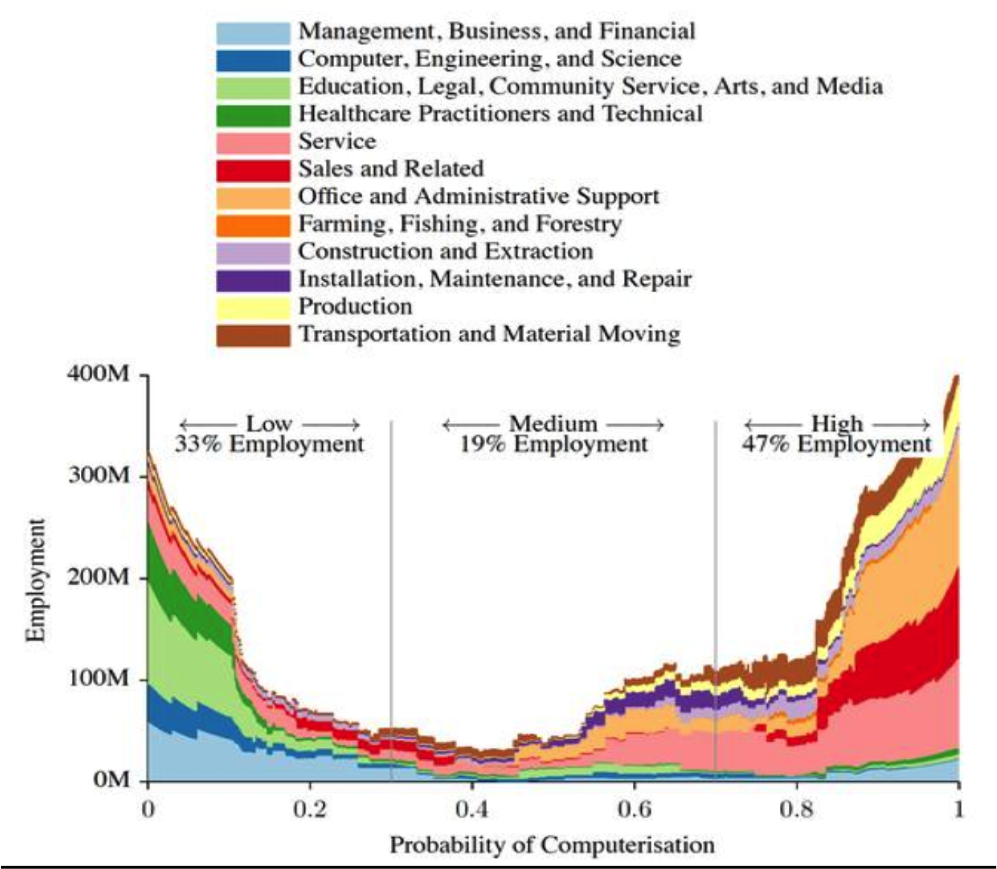

The demand for labour can be expected to change markedly in distribution both because of the ageing of our society and because of technological change. Osborn & Frey[6] consider the impact of computer technology on US employment in great detail; their principal results are shown below as figure 2.

Note - The distribution of Bureau of Labour Statistics 2010 occupational employment over the probability of computerisation, along with the share in low, medium and high probability categories. The total area under all curves is equal to total US employment.

Their conclusions in some other regards are also very interesting. Wages and educational attainment already show a strong negative relationship with the probability of computerisation. In contrast to 19th and 20th century experience, the effect of capital deepening and automation will fall largely on the low-waged unskilled rather than the skilled middle income, and result in a less polarised labour market. Doubtless much of the employment shift for the low-wage, low skilled in the sales, services and administration sectors will be towards care for children and the elderly – with a much more significant health care sector.

We should also dismiss the idea that it is too late to do anything other than cut pension benefits. In the period since 1970, UK (net) national wealth has risen from 314% of GDP to 520% of GDP (at market prices). It is notable that, over this period, governments have engineered a significant shift in the ownership of that wealth through privatisation and similar policies from the state to the private sector, and that this has been accompanied by ever-greater polarisation of the ownership of that wealth. Inequality in wealth and income now impinges upon equality of opportunity, notably through the cost of tertiary education. Social mobility has declined along with trust. Greater inequality has the effect of lowering total output growth and making the economy less stable, with cycles proliferating. It is clear that the problems we face are problems in distribution, not absolute levels. This is further supported by the observation that UK per capita consumption does not decline at post-retirement ages. It remains as high as, or slightly higher than it is during our most productive working years.

The relief of absolute poverty is a duty of the state precisely because the state defines and enforces property rights. The case for the relief of relative poverty as a duty of the state is broader, but sound economics support it. Some inequality, of course, incentivises the poorer to strive harder, but we should be very wary of the tendency and ability of the wealthy to defend, extend and distort their property rights in both absolute and relative terms.

In simple terms, pension rights are just claims on future production. We can choose to acquire those claims in a number of ways, in limitless variety. We may choose to be dependent upon our children sharing the future production that their labour income will purchase, which of course is determined to large extent by our investment in their education and upbringing, as well as their inherited national endowment. We may choose to be dependent upon the state, which through its regalian powers may appropriate and allocate production as it will. We may choose to be dependent upon the future production of today’s private sector producers, employers – and that dependence may be acquired as a direct promise or indirectly through the securities that they issue to finance themselves, which are traded in financial markets.

Given this breadth of possibility, the obvious question is why, beyond the vested interest of the financial sector, is there so much emphasis on funding in the world of pensions. If there is no future production, there will be no food on the table and possessing all the share and bond certificates in the world will not change that. This takes us right back to the initial calls for more savings. It is clear that saving 8% of a salary over a working lifetime in an individual DC arrangement will not provide much more than 20% of final salary, unless investment returns are very high. It is also clear that saving more does not, for all, represent a realistic strategy – many of the low paid simply cannot afford any increase. Moreover, if those that could afford to increase pension savings did, the returns to investment could be driven even lower in a stagnating economy. This leaves the “save more” advice rather isolated as little more than a relative argument among pension savers. It raises the question why should taxation support such intrinsically regressive behaviour.

The imperative in this situation is to focus upon the efficiency of the institutional organisation: Individual DC requires almost 50% more funding than Collective DC, which requires about 50% more funding than Funded DB, which requires about 50% more funding than insured book-reserve DB to produce the same amount of pension. The efficiency of the form of organisation determines the level of savings required; it also determines the cost of the tax concessions offered by the state.

Notes & References:

- 'There is that scattereth, and yet increaseth; and there is that withholdeth more than is meet, but it tendeth to poverty.'

– Proverbs 11:24 - "For although the amount of his own saving is unlikely to have any significant influence on his own income, the reactions of the amount of his consumption on the incomes of others makes it impossible for all individuals simultaneously to save any given sums. Every such attempt to save more by reducing consumption will so affect incomes that the attempt necessarily defeats itself. It is, of course, just as impossible for the community as a whole to save less than the amount of current investment, since the attempt to do so will necessarily raise incomes to a level at which the sums which individuals choose to save add up to a figure exactly equal to the amount of investment."

— Keynes, J.M. (1936). The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. Chapter 7, p.84. - Keynes, J.M. (1930). A Treatise on Money.

- Beaumol, W.J. (2012). The Cost Disease: Why Computers Get Cheaper and Health Care Doesn’t.

- The share of national income attributable to capital was 15% in 1976 and is now slightly above 30%. Undoubtedly globalisation and a legislated weakening of the power of unions were influential in the relative decline of wages. However, the wage cost pressures of globalisation are now largely a spent force.

- Frey, C.B. & Osborne, M.A. (2013). The Future of Employment: How Susceptible Are Jobs to Computerisation?