Promises, Promises

Tuesday, 05 November 2013By Con Keating

The earlier article “Trust and Commitment” was necessarily short but prompted much reader response. In pursuit of brevity, it did not consider a number of things, for example, trust as encapsulated interest – we place our trust those whose interests contain our own[1]. Indeed, there is also a corollary to this that we do not trust those whose interests differ from our own. The weakness in this approach is the exogenous nature of these interests when the iterative endogenous characteristics are clearly of great importance. Familiarity breeds familiarity and encourages trust. There are questions over commitment and incentives for the trusted, particularly so under uncertainty.

Nor did we cover the idea of trust arising from evolutionary biology, ubiquitous though trust is in developed societies. This is because we prefer to think of trust in the context of choice rather than as a consequence of evolution. However, we should remember that trust can influence not just what we choose to do, but also what we can do.

We should have distinguished between trust and confidence. Both concepts refer to expectations that may lapse into disappointments. We trust that markets will function as we expect but we have confidence in the ability of our doctor to cure our ills. The latter is a question of ability and related to the competence characteristic listed in the earlier article, while is the former is concerned with motivation or predisposition[2]. We can have confidence in the ability of the ATM to deliver cash, but we should also recognise that it does not have any functional flexibility, a characteristic of relations of trust.

For completeness, we should also have covered moral hazard and adverse selection in contracts. Moral hazard arises when we have incomplete information about the counterparties’ actions; are they locking the car now that it is insured against theft? Adverse selection arises when we have incomplete information with respect to the counterparties’ characteristics; was that illness present before the policy was written?

Among the volumes of philosophy on the subject of trust, there is a good workhorse description due to Annette Baier[3], which seems highly applicable in the context of financial affairs:

'For to trust is to give discretionary powers to the trusted, to let the trusted decide how, on a given matter, one’s welfare is best advanced, to delay the accounting for a while, to be willing to wait to see how the trusted has advanced one’s welfare.'

In a fund management setting, not only does this bring the investor’s timing of demands for accounting into question but also it raises the questions of active and passive misuse of discretion by the trusted. A good illustration of the passive is the practice of hugging an index when uncertainty is high, while charging active management fees.

Many of the responses from esteemed members of the legal profession concentrated on the suggestion in the earlier article that fiduciary responsibility should extend to all involved in the investment management chain. Most took issue with the idea that this should be soft and not overly defined and should not be restricted and defined by rules and regulations. They raised questions of duties of care, duties to negotiate in good faith, and duties of fidelity, among others and wanted to write far more extensive rules and regulations, which, of course, would be interpreted by a cynic as a desire to promote their own professional interests.

The question of the form of regulation is important. Coercion is a substitute for trust and in implementation could easily be asymmetric and destructive of mutual trust between fund manager and investor. While it ensures compliance within the specific context covered, it also increases the likelihood of perfidious behaviour elsewhere. Information exchange and interpretation might then no longer be free. It would also be costly in terms of compliance and enforcement and reduce economic efficiency. In soft form, however, legislation can provide the governance framework that allows for the enforcement of agreements over rights that are commonly shared, but permits relations of trust to do the heavy lifting. This reduces the other, non-enforcement costs of legislation by allowing private monitoring and information collection and generation. We should also not forget that for the signals generated by someone wishing to demonstrate their trustworthiness must themselves be costly if they are to be credible.

It seems to us that these issues can be better dealt with by voluntary adoption of an ethical code. Just about all fund managers now publish and promote their investment philosophy. In all-too-many cases these philosophies are little more than collections of inanities; we believe in mean-reversion, we believe in fundamental analysis, and the like; recitations of a particular investment creed – perhaps, a mind map. We will offer, as a straw man, a collection of principles for inclusion in this philosophy of ethics, which we believe will go far in promoting trust in investment relations, and obviate the need for fiduciary responsibility to be accompanied by yet another detailed rulebook.

It is clear that the forces of competition have led many fund managers and investment consultants to adopt the ad-man’s practice of selling the sizzle rather than the sausage, leading to over-promising and disappointment. Promises have been the subject of vast amounts of philosophical thought; from Hume and Kant and Durkheim to the current generation. Here, we borrow heavily from Thomas Scanlon’s 1990 “Promises and Practices”[4], which offers four principles:

Principle M: In the absence of special justification[5], it is not permissible for one person, A, in order to get some person, B to do some act, x (which A wants B to do and which B is morally free to do or not do but otherwise would not do) to lead B to expect that if he or she does x then A will do y (which B wants but believes that A will otherwise not do) when in fact A has no intention of doing y if B does x, and A can reasonably foresee that B will suffer significant loss if he or she does x and A does not do y.

This amounts to little more than a statement that we will not mislead and is a moral standard. The open question is really the degree to which an investor has come to rely upon this promise.

Principle D: One must exercise due care not to lead others to form reasonable but false expectations about what one will do when there is reason to believe that they would suffer significant loss as a result of relying on those expectations.

This introduces reciprocity and commitment to the relation between fund manager or investment consultant and the investor. In many regards, it can be seen as a variant of First Do No Harm. It can be extended to include more developed ideas, such as loss prevention.

Principle L: If one has intentionally or negligently led someone to expect that one will follow a certain course of action x, and one has reason to believe that that person will suffer significant loss as a result of this expectation if one does not follow x, then one must take reasonable steps to prevent that loss.

The notion of proportionality is introduced by the idea of reasonable steps, which might take no more than the form of warning the investor. The principle is in fact neutral between warning, fulfilment and compensation. It would though doubtless appeal to those investors who experienced style drift in their hedge fund investments and suffered resultant losses.

It is arguable that even this principle is not sufficiently comprehensive; for example, it does not cover an investor’s foregone opportunities, and we may move to a duty of fidelity:

Principle F: If;

- A voluntarily and intentionally leads B to expect that A will do x (unless B consents to A’s not doing x);

- A knows that B wants to be assured of this;

- A acts with the aim of providing this assurance, and has good reason to believe that he or she has done so;

- B knows that A has the beliefs and intentions just described;

- A intends for B to know this, and knows that B does know it; and

- B knows that A has this knowledge and intent; Then, in the absence of some special justification, A must do x unless B consents to x’s not being done.

This introduces a right to rely upon the expectations created. It would clearly introduce a need for ongoing open discourse between investor, consultants and managers. It is clear that these principles, if adopted, could offer a governance framework for an extended fiduciary responsibility and result in both increased trust and independent arbitration by the court system. Clearly, these principles are complementary to one another rather than mutually exclusive.

Whether we like it or not, the formation of agreements between investors, fund managers and investment consultants has a moral dimension. Clearly, such agreements bring with them obligations and duties, which only-too-much of the fine print of investment management and consultant contracts seeks to avoid and evade. The signal that such agreements send is that the counterparty is not trustworthy. Trust will not flourish in that environment.

Computer Says No

Among the more difficult questions, facing us in the reconstruction of a trusting world is the role of technology. Undoubtedly, systems can supply us with real-time data on the disposition of our investments and with near-real time valuation of these portfolios. However, this is data rather than information.

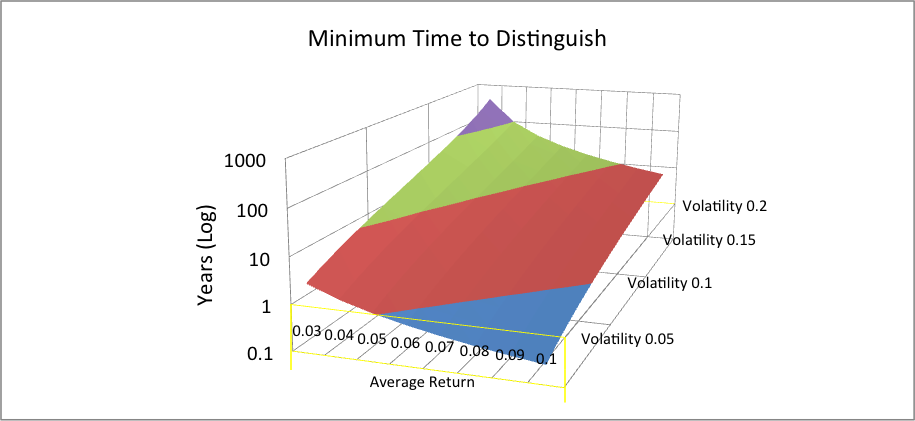

The first concern with such exchanges of data must be the separation of signal from noise and, when market prices are used for valuation, the levels of noise are surprisingly high, as is illustrated below. This figure shows the length of time an investment must be held for the signal to be equal to the noise, which is the usual minimum standard for distinction between signal and noise to be feasible. It is evident that distinction at frequencies of less than one year is only feasible with high return, low volatility assets, but that is precisely where the information is least valuable.

Technology supplies us with data, and to parse data into noise and information requires the use of a model. Different models can provide entirely different information. Though these models do not have to have formal statistical description, i.e. they can be mental mind maps, the use of different statistical models can illustrate the differences which may arise from the use of different models, and they can be radical.

In the context of relations of trust, where the resolution of ambiguity and uncertainty are the objective of interactions between trusted and truster, it is necessary for these two parties to share a common model for a shared interpretation of circumstances. This lies at the heart of mutual understanding. Transparency when it is just the exchange of data is insufficient.

Technology can, of course, increase our confidence. The ability of the ATM to operate competently and reliably is not in great doubt, which merits our confidence, but the ATM has limited functionality. It is bounded by the rules programmed into it, as well as its mechanical parts. But confidence and trust differ. The technology is incapable in conditions of ambiguity and uncertainty of the interactive deliberations and flexibility that are a central feature of informal contracts. In some regards, these dialogues may be viewed as the process by which new models are agreed by both parties.

Perhaps the most important point is that if the industry embraces these principles, then fiduciary responsibility does not have to be accompanied by yet another thick rulebook. Though the threat of statutory intervention is reason enough to adopt such approaches, there is a more basic market rationale. If London does not take this approach, with its disclosure and transparency, it will simply lose out to those markets overseas that do; enlightened self-interest should prevail.

References and Notes:

- We do not discuss here a related issue – the incentives to mislead during a relationship in pursuit of self-interest.

- There is an interesting and relevant illustration due to Luhman: As a participant in the economy, you necessarily must have confidence in money. Otherwise, you would not accept it as part of everyday life without deciding whether or not to accept it. In this sense, money has always been said to be based on ‘social contract’. But you also need trust to keep and not spend your money, or to invest it in one way and not in others.

- Baier, A (1991). The Tanner Lectures on Human Values'. NJ: Princeton University.

- Scanlon, T. (1990). "Promises and Practices". Philosophy and Public Affairs. Vol.19 (Issue 3), pp.199-226.

- Such justification need not take the form of considerations that override the obligation described by this principle, but can also include reasons for setting it aside, as for example in some forms of legitimate competition in which it is permissible to lead others to form false expectations about one’s intentions.