Ownership And Agency

Monday, 02 December 2013By Con Keating

Since at least Friedman’s 1970: “The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits”, it has become common to refer to the shareholders of a firm as its owners, a mistaken view that leads to much confusion and wasted effort. On top of this misconception, in their 1976 paper[1], Jensen & Meckling compounded the matter by asserting that: “the relationship between the stockholders and the managers of a corporation fits the definition of a pure agency relationship.”

A corporation in fact owns itself, in just the same way that we own ourselves. The corporation is a legal entity. Shareholders have rights over the residual assets of a corporation; but they certainly cannot take possession of or dispose of corporate assets for themselves, which is sometimes referred to as “capital lock-in”. Most importantly, management is not the agent of shareholders but the agent of the corporation itself. Management does not owe a duty of obedience to shareholders. Shareholders usually also have rather limited voting rights, for example over the appointment of directors.

Many differing strands of theory and analysis now challenge this Chicago school paradigm of corporate finance and purpose. Among these[2] are concerns with market efficiency, the role of liquidity, and differences between the short and the long-term, as well as the differing preferences of universal investors versus undiversified actors, and director control as a form of mediation mechanism between shareholders’ and other stakeholders’ inclinations. This latter approach notes that directors rather than shareholders suffer opprobrium from the anti-social activities of the corporation.

Taking a legal standpoint, Clark[3] summarizes the (US) law as:

- Corporate officers like the president and treasurer are agents of the corporation itself;

- The board of directors is the ultimate decision-making body of the corporation (and in a sense is the group most appropriately identified with “the corporation”);

- Directors are not agents of the corporation but are sui generis;

- Neither officers nor directors are agents of the stockholders; but

- Both officers and directors are “fiduciaries” with respect to the corporation and its stockholders.

In economics, as noted by Colin Mayer, the reality is that: “The failure of the conventional and unconventional paradigms is in providing a compelling description of the corporation”. It is notable that, in practice, shareholders appear to be comfortable with directors being outside of their control, and often permit developments that reinforce their independence. It is clear that this relationship is not one of principal and agent. To a very large extent, this renders questions of shareholder engagement and influence matters of moral suasion and indirect influence.

This far, we have been considering large corporations with widely diversified shareholder bases; when we move to considering companies with concentrated ownership, for example within a particular family or the workforce, it is evident that greater influence may be exercised. But even here, the relation is not the simple separation of ownership and control that lies at the heart of traditional agency theory. By extension, it is perhaps to be expected that very large self-managed investment institutions, which have meaningfully large investments in particular firms should seek to have greater influence over their management.

By contrast, the relation between a pension fund, its trustees, and its investment managers should be one of principal and agent. Note that this is not the case when the pension fund makes direct investments. These investment management chains can be extremely long, involving many advisors and intermediaries; this introduces room for many divergent interests to be interposed.

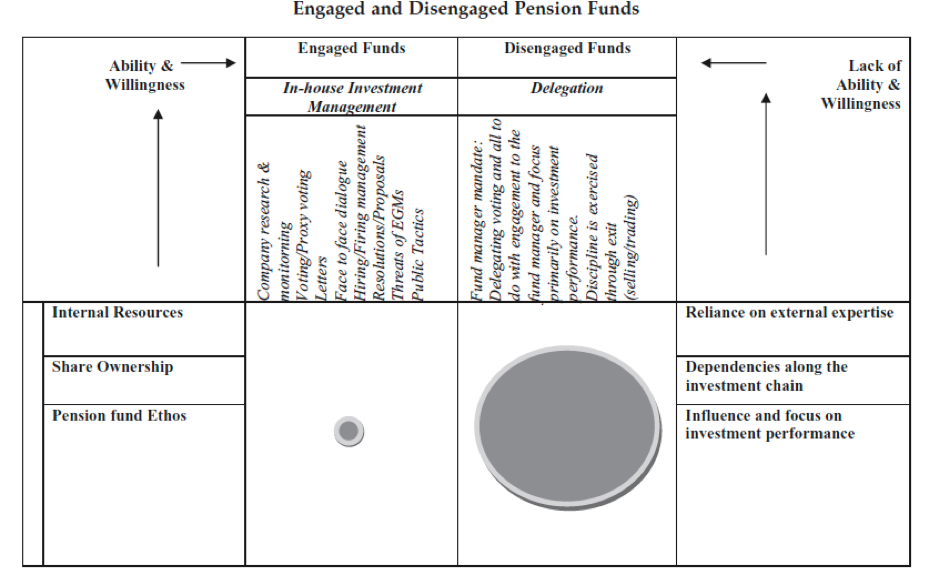

Empirical analysis of the actions of shareholder investors yields divergent results; some find increasingly engaged behaviour, while others find continuing uninvolved behaviour. A recent study by Anna Tilba and Terry McNulty[4], which examines many aspects of the investment chain, is most informative, as can be seen from the figure below, which is reproduced from their study:

It is notable that it is mainly large pension funds with in-house management that are active in engagement activity, while others appear to exhibit (rational) apathy. It is clear that much further research on the investment chain is needed.

Investment consultants perform a role as gatekeepers for trustee boards, limiting the access of fund managers to trustees; making recommendations to trustees as to which fund managers should be considered. This is a situation seen with credit rating agencies in the case of sub-prime securities, where the awarded AAA ratings served to grant access to particular classes of investor. Reputation used to be central to a credit rating agency’s ability to operate. However, when we have limited choice, then it may be perfectly rational for the agency to be unconcerned with reputation, particularly when the rewards to ignoring reputational effects are very substantial. When the choice is limited, though some clients may vote with their feet, the loss is likely to be offset by the gain of clients leaving other agencies. It is clear that the investment consultants have made an analogous decision with respect to their provision of direct fund management services, for example with fiduciary mandates; they perceive the gains to be sufficient that the conflicts and reputational damage are outweighed.

Perhaps the most worrying conclusion to this Tilba and McNulty study is: “It is not clear as to what, and if at all or to what extent, these experts (actuaries, fund managers and investment analysts) are accountable to each other, or the fund.” Nor is it clear what value, if any, is added by these advisors. It seems that the mutual commitment that fosters relations of trust is absent rather than predominant.

Tilba and McNulty also observe: “These relationships are laced with divergent interests and influence dynamics, which explains why these pension funds give primary emphasis to fund investment performance ...” Many schemes are, of course, manage their funds in manners intended to hedge variation on the present value of liabilities rather than seeking to maximise investment returns. However, the emphasis is on return performance. This is questionable as the assets held by a scheme are only intermediate goods; their role is to generate the income from which pensions may be paid. Any strategy that depends upon selling assets in markets to meet pension payments is highly dependent upon the future liquidity and performance of those markets; a process which is far from certain. In circumstances where a scheme is in cash-flow surplus and growing, the scheme should actually prefer lower prices since this allows it to buy future income more cheaply, and implies a lower cost of pension provision. For schemes in this position, the absence of dependence on market prices may the use of market prices in valuation and regulation suspect in extreme.

The analysis of scheme investment in terms of exit or voice leads to some rather different conclusions; for voice to be listened to, it needs to be committed, with exit foregone. Management is not longer concerned with maximisation of the share price, but rather with maximisation of earnings in a sustainable manner. Voice should also only be listened to when it supports the stakeholder or team commitment view of the firm. The gains to these long-term strategies are realised from an equitable distribution of earnings over the long-term. In the short-term, there may well be market relative underperformance, but that is a direct result of the myopia of markets. Let us not forget it is income, and income growth, that dominate the long-term returns to investment.

References and Notes:

- Jensen, M. & Meckling, W. (1976). “Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure”. Journal of Financial Economics, 305.

- There are several approaches that emphasise the investment of other stakeholders in the firm, such as team production theory, which can be seen as an analogues of the lock-in of shareholders.

- Clark, R. (1985). “Agency Costs versus Fiduciary Duties”. In: Pratt, J. & Zeckhauser, R. (ed.) Principals and Agents: The Structure of Business. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

- Tilba, A. & McNulty, T. (2013). “Engaged versus Disengaged Ownership: The Case of Pension Funds in the UK”. Corporate Governance: An International Review. 21 (2), pp.165-182.