On The Morality Of Lending And Debt

Wednesday, 03 April 2013By Mike Young

The Moral Ambiguity of Debt

debt • noun.

1. a sum of money owed.

2. the state of owing money.

3. a feeling of gratitude for a favour or service.

— Oxford English Dictionary

This quotation sits the start of David Groeber’s excellent new book on the history and anthropology of debt[1]. The definition illustrates really neatly that we do not have a coherent well thought through morality around the concept of debt, leading to confusion and blame shifting. Here is a small sample:

- We feel that people have a moral duty to pay their debts.

- Contradicting the first point we also feel that perhaps some debts should not be enforced, especially crippling third world debt, or debts that lead to wage slavery in other countries.

- People who lend money are evil. Our culture is filled with stories of evil moneylenders, Zaccheus, Shylock, and today, modern investment bankers. There are few “hero” moneylenders.

- Yet we need moneylenders. Would you deny young couples a mortgage or third world farmers the opportunity to buy medicines to keep their children alive?

- We resent people who lend money making a profit from it (interest), but nevertheless expect risk free interest when we put our money in the bank.

- We also feel that banks have a moral obligation to make high-risk loans. Perhaps to the poor, perhaps to mortgage owners, and perhaps to small business start-ups, but we don’t want to support the banks if the loans fail.

- Sometimes the confusion results in a belief that any form of loan is immoral. “You should never take out a loan” we say, and then follow this immediately with a qualification such as “apart from mortgages….”

There is little doubt that our moral position on debt is confusing and ambiguous. Our attitude to it seems to border on cognitive dissonance, causing us to try desperately to believe several mutually contradictory things. This problem and the associated moral ambivalence have been around for millennia. The book was interesting, but ultimately frustrating as it illustrated the problem without positing a solution. So it is with a mixture of trepidation and brashness that I will try to bring some order to this confusion.

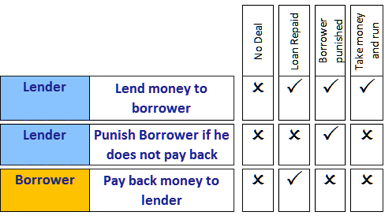

I will do this by building a table of the different combinations of choices that the borrower and lender could take, and then using it to bring out four principles that can be used to judge if a decision to lend money at interest can be considered “moral” or not.

Three Possible Scenarios

An options table is built by boiling things down to a series of Yes/No decisions. If a potential borrower is looking for a loan, rather than a gift, then there are three actions that may (or may not) happen.

- The lender can lend (or not lend) the borrower the money they want;

- The borrower can repay (or not repay) the lender according to the terms agree;

- If the borrower doesn’t repay the lender could punish (or not punish) the borrower. Many different sanctions are available, ranging from repossession of your house in western societies, to what is essentially debt slavery in the developing world – the sanctions can take different forms, but their aim is the same, to provide a large deterrent against the borrower defaulting.

Building Plausible Scenarios

From the three decisions above there are 23 = 8 possible combinations of outcome. But of those only four are plausible, as shown in the table below. Whatever is planned, eventually one of these four scenarios below will transpire, either by accident or by design.

- No Deal: No loan is made (Lender does not lend or punish the borrower. Borrower does not pay back, as they owe nothing). This is represented by the column of crosses on the left.

- Loan repaid: (Lender does lend and does not punish the borrower. Borrower does fully pay back). Note that this is always the agreement that is outwardly proposed by the borrower.

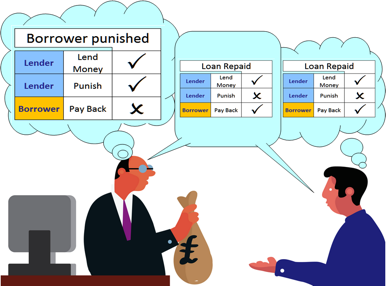

- Borrower punished: Here the lender does lend the money, but for whatever reason the borrower does not fully pay it back and in this case the lender does exact their punishment on the borrower.

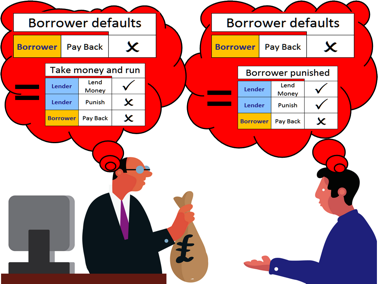

- Take the money and run: Here the lender does lend the money, again for whatever reason the borrower does not fully pay it back. But in this case the lender does not exact punishment on the borrower, (they may be unable to do so or they may decide to forgive the borrower).

Once things have been structured in terms of these four possible outcomes, we can now start to make some moral statements about the way the loan ought to be carried out.

Moral Principles

I posit that if the following four principles are met, then the loan is “moral”, and that any “immoral” loan will fail on one or more of the principles. As with all such principles, it is the exception that tests the rule. I do not believe in moral absolutes, but I do believe in moral principles. As with all moral principles, it is always possible to think of exceptions to the rules, but the more bizarre and implausible the exceptions to the principles have to be to engender a debate, the better the principles are in the first place.

Moral Principle 1: Fully understood agreement between the parties

This almost goes without saying, but the lender should not deceive the borrower as to the terms of the agreement, hide costs or later demand more than agreed. Both the borrower and the lender should also agree what would happen if the loan is not repaid. The actions in the table should be unambiguous and understood in the same way by both parties.

This principle is possibly the easiest to enforce, as it is about what people are saying, rather than what they are doing or thinking. Rules can be made. Indeed there are laws that enforce clarity (for example by forcing lenders to calculate their interest rates in the same way).

Moral Principle 2: Both sides should be trying to make the “Loan repaid” scenario take place.

To meet this principle, both sides should not only be saying that the loan will be repaid, but also hoping and believing that the borrower is able and willing to pay back the money (see below).

It would be immoral (as deceit would be involved) for a borrower to take out a loan, hoping or expecting not to repay. Perhaps he does not believe that the lender will be willing to enforce the debt, (as with loans from family members) or he may think that the lender will be unable to enforce it (if the borrower intends to abscond with the money), and does not intend to repay at the time of the loan. This is shown below:

Intent not to repay in this way is generally illegal (fraud), and society has structures and rules in place to prevent or stop this happening.

But there is another immoral loan when the boot is on the other foot. This is where the lender hopes and expects that the borrower will default on the loan because he wants to cash in on the collateral (e.g. acquiring a house of greater value than the loan). The borrower may well think that he will pay back, but the lender doubts he will be able to, and relishes picking up the collateral. The “Liar loans” that led to the crash of 2008 were in this category. By making loans to less and less creditworthy people, the American mortgage companies were hoping to cash in on the sale of repossessed houses. It would have been a great idea if the house prices had not collapsed, leaving both the borrower and the lender with nothing. Shylock from the Merchant of Venice was also in this category by insisting on a “pound of flesh” that was offered as collateral rather than a cash repayment that was offered.

Setting morality aside, this policy is not without its risks for the lender; in particular many new laws favour the borrower over the lender, meaning that people trying this out may end up with the “Take money and run” scenario instead. The lender may also incur costs for enforcing the payment.

A way to ensure that ‘thoughts are pure’ is to ensure that the borrower defaulting is a lose/lose situation for both parties, and so that the lender hopes to profit from charging interest, rather than from picking up the collateral.

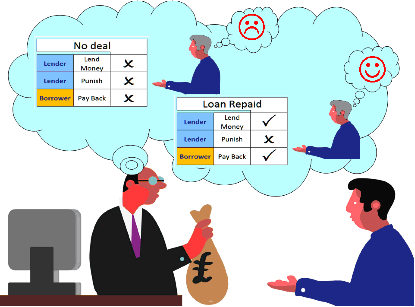

If the lender believed that he should lend even if the borrower would get away without punishment, and the borrower believes he should borrow even if punished, then the deal meets the principle.

It is at this place that an argument can be made for the morality of charging interest in the first place. A lender may be approached by several borrowers each of whom intends to repay but each of whom has a chance to default (even though nobody intends to). To get their money back the lender would be required to charge interest to cover the risk.

It is also at this point that things get a bit sticky as there is a requirement for the borrower and the lender to believe mutually contradictory things. It is argued that a moral lender should be somewhat magnanimous towards a borrower who cannot repay through any fault of their own (perhaps the borrower bought seeds for their farm with the loan and the crops failed), and the lender should not insist on all the punishments previously agreed. But on the other hand, the lender is aware that if they become known as a “soft touch” then the borrowers will be tempted not to try too hard to repay their debts.

Moral Principle 3: The lender should not make a loan they know the borrower will regret.

There is another moral obligation on the lender that seems to be increasingly used as an accusation of immorality against lenders. It is said that a lender should have a moral obligation not to make loans unless they believe the “Loan repaid” scenario is preferable to the “No deal” scenario for the borrower.

That is, the lender has to think that at the end of the repayment period the borrower will thank the lender and be glad that they took out the loan, rather than wishing that they hadn’t.

The arguments supporting this are that transactions should be a win/win situation, with both sides gaining from the loan, and the borrower should not be conned into thinking it’s a win/win when it’s actually a win/lose.

Paying back a loan, even if it all goes according to plan, can be a very painful process, and it is very easy for a borrower to be optimistic and assume things will miraculously turn out all right when they take out the loan, underestimating the amount of efforts that will be needed to pay it back. In general, the lender will be more familiar than the borrower with the lending process and the consequences of receiving loans. They will be best able to evaluate the true cost of the loan.

To make this judgment the lender will have to know what the borrower wants the money for (e.g. investment or expenditure), and what sacrifices they will have to make so they can repay the loan.

A lender should sometimes say to a borrower “It is irresponsible for me to lend you the money, as I think that you will be in a worse state than if I didn’t”.

Not to do this is the equivalent of selling defective goods. The buyer agrees to what they think is a good deal, but in fact it isn’t. Lenders are rewarded for making loans that get repaid, not for making the customers’ lives happier in the long run.

Payday loan lenders can be criticized under this principle. Many of these take pride in being crystal clear about the terms of the loans they offer. It expects the borrowers to pay back. It passes Principle 1 and Principle 2 with flying colors. However it is still criticized for Principle 3. The feeling is that the borrowers shouldn’t be taking out the loans in the first place, as to do so would imply getting into worse financial difficulties than before.

It is here where excessively high interest rates can be criticized. High interest rates will increase the ‘pain’ involved in paying back the loan, perhaps nudging the borrower towards the “it would have been better if I hadn’t taken out the loan” scenario.

On the other hand...

Despite true intentions people who take out loans may have difficulty paying them back. There is then a very human tendency to blame somebody else for your misfortunes, and to build a story in your head absolving yourself from all blame. The moneylender is the ideal scapegoat. The lender is demonized in the minds of the borrowers who genuinely misremember details of conversations that happened, convincing themselves they were miss-sold. Self-deception is worse than outright lying here. Sometimes the lenders are genuinely surprised at what happens as well. They expect to lose 10% of the loans through “hard luck” stories, but because the economy takes a nose dive 50% of the loans are lost.

What perhaps they should be doing is to get some feedback on the wisdom of taking out the loan with the benefit of hindsight at the end of it all. Perhaps we need to organize a feedback site where customers can answer a simple question, at yearly intervals after the loan was taken out.

“I am glad I took out the loan True/False”.

Even if the results are less than what the lenders would like, the relative positions would serve to deter genuine miss selling and the number of happy customers would show to the self-deceived borrower that not all the loans turned out as bad as theirs did.

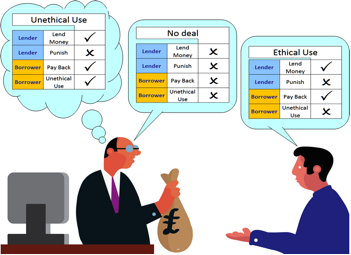

Moral Principle 4: Do not lend for unethical purposes.

An extension to the above is what is often called “ethical lending” which is mainly interpreted as not lending to borrowers who will themselves use the money further down the line for immoral purposes (even if they are perfectly moral and honest with the lender). An “ethical lender” will usually not loan to companies that use child labour, or produce tobacco or weapons. Instead of ensuring a win/win just between the two parties agreeing to a loan, the win/win concept is beyond the lender and the borrower to the well being of the world as a whole.

Unfortunately, this involves adding an extra action to the three laid out at the beginning, that is the decision of the borrower to use the money unethically. So our table is extended from three to four rows. This results in the following as our final principle for “moral” lending.

Summary and Conclusions

Looking at our four principles, we can begin to see why bankers and moneylenders have acquired such a reputation for being unethical. It is firstly because they are the ones with both the greater number of temptations to behave unethically, and fewer penalties in law if they do. But it is also because the lender is the perfect scapegoat if something goes wrong with the loan. The borrower can then retrospectively paint themselves as a victim of being "miss-sold" the loan by the lender.

| Principle for "moral" loan | Onus of Responsibility | Penalties for Breaking Principle | Retrospective Accusation Potential | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fully understood agreement between parties | Mainly lender | Moderate | Moderate |

| 2a | Both sides intend do not intentionally "punish lender" | Lender | None, but risky | High |

| 2b | "Loan repaid" do not intentionally "take money and run" | Borrower | Severe | Moderate |

| 3 | "Loan repaid" better for borrower than "No deal" | Lender | None | Very High |

| 4 | Only lend for ethical end use | Lender | Minor | Moderate |

Progress is being made on three of the four principles, but principle 3 remains the difficult one to achieve. It is a genuine temptation for the lender, and also a perfect retrospective way for irresponsible lenders to shift the blame back onto the borrower. The simple solution proposed (feedback by borrowers at the end of the loan on how glad they were to take out the loan), may serve to reduce both problems.

This article also illustrates the power that thinking in terms of options tables has in bringing clarity and focus to confusing situations. This approach (formalised as Confrontation Analysis) can equally be helpful in the context of legal, business and political negotiations.