Hope For The Future - Lessons From Northern Ireland

Friday, 05 January 2024By Amit Sharma

Warrington and Manchester in the Northwest of England have two things in common, firstly they are envious of my hometown Liverpool and secondly during the late 1980’s, both experienced horrible terrorist atrocities as part of the troubles in Northern Ireland.

As we come to the end of the year and the number of live conflict zones across the world increases, a recent trip to Belfast allowed me to see a city, once synonymous with factional conflict, not only at peace, but in its own way, flourishing. The High Street is nearly identical to that of any other British or Irish City, with the same range of shops and boutiques and the newly built Victoria Centre boasts an upmarket mall within the city centre.

Connected by two airports, visitors and tourists bustle into the city, attracted by the Titanic Museum and of course Game of Thrones shooting locations. As the taxi drivers zip between the airport to the city, the conversation invariably starts with what a friendly place Northern Ireland is and how nice the people are. A gentle reference to the past is met with good natured humour, ‘yes there were lots of murders, but we were only interested in killing each other’.

A martime climate and the verdant fields surrounding the city means that for those visiting from London or other large cities, the clean air actually hurts! Northern Ireland is home to only two million people and was created when the Island was divided back in 1921, along religious lines. The Republic to the south is majority Catholic and the Northern part used to be predominantly Protestant, but this is no longer the case. Since its birth, there have been troubles and unrest, but for a thirty-year period from the late 1960's up until the Good Friday Agreement in 1998, over 3,500 people were killed and apart from the human cost, the cumulative financial cost of the violence to both the Irish and UK government since 1969 was estimated to be about £20 billion. So how is it possible that a city as small as Belfast that was as divided on sectarian lines in most of our lifetimes can transform itself to a normal city with people from each side working and living side by side in peace. Further, what can we learn from this, in light of all of the conflicts taking place.

Jeremy Bentham, pictured beside, was the British rock star of philosophy back in the 1780’s and under his theory of utilitarianism, right and wrong could be measured by the notion of what gives the greatest happiness to the greatest number of people. Happiness was the predominance of pleasure over pain or suffering. In the case of Northern Ireland, it was abundantly clear that this was the ability to live together in peace over cycles of violence and conflict.

We can see for a start that in the linen quarter, the streets are named in both English and Gaelic:

I asked General Barrons, a man who has served in locations as exotic as Iraq, Afghanistan, Bosnia and Northern Ireland about what are first steps for peace in a conflict zone and his answer was almost immediate - people get tired of death.

When conflicts start there is a sense of immortality, especially amongst the young, who rally behind a belief or thought system. As the economy deteriorates and infrastructure falls apart, there is little to lose and it often takes a generation or at least half of one, for such weariness to set in.

The population in Northern Ireland always seems to be measured as a ratio of one religion against another, rather than, as a breakdown of younger people vs older When the troubles started the median age of its residents was 28, currently the median age is above 40 and it is getting older, as people live longer and have far fewer children. True happiness for someone in their forties is knowing that their children are able to go outside and come home safe and sound. It is not exactly rocket science that peoples priorities change as they get older - and this is reflected in society by demographic changes..

At Love Fish, a popular lunch destination across from Belfast City Hall, I enjoyed Scampi and Chips with Colin McCullagh, Chief Revenue Officer at OCO, an advisory firm focusing on foreign investment. Whilst there, we were seated amongst around forty or so other diners, almost all of them eligible for a free bus pass (over 65). Over a couple of glasses of Chardonnay, we discussed what childhood was like for him during the troubles and the impact it had on his generation growing up. As a result, of his experiences, he is focused on ensuring his child get the best education and opportunities, so they can fulfill their abilities in a way that previous generations were unable to. This is evident in some of the murals you can see across the city and in the recent PISA education scores which highlighted fifteen years olds in Belfast on average had better reading and writing skills than their counterparts in Paris, Berlin, or Amsterdam.

Coming back to my conversation with General Barrons, he continued that once weariness sets in, having a stake in any future society is key and by this he means investment and employment opportunities. Following the signing of the Good Friday Agreement, investment started coming into the city and surrounding areas and in the legal community, the ‘Belfast Solution’ was shorthand for a low-cost legal hub. My old law firm Allen & Overy opened there in 2011, creating 400 jobs, alongside many other law firms, taking advantage of the lower cost location. Outside London in 2023, Northern Ireland was the second fastest growing region in the UK, albeit benefitting from a very large public sector workforce. We can see similar green shoots in the Indian state of Kashmir, with Dubai based Emaar investing to build a shopping centre and commercial tower in Srinagar, creating hundreds of jobs and much needed infrastructure.

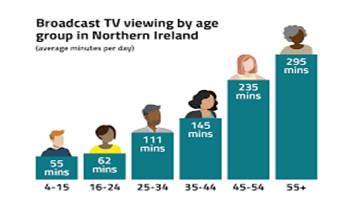

Information also plays a large part in the transition to peace and Northern Ireland was fortunate that in the late 1990’s, we were all subject to the same few television channels and media outlets. As we can see in the chart below, broadcast television now is really only for the elderly and younger people have access to a variety of news sources. The information and coverage, particularly in the echo chambers of social media can be radically different, which makes finding common ground much more difficult.

Finding something to eat in Belfast after ten pm on a Tuesday evening is a fairly strange experience. In most British cities the migrant communities whether Chinese, Indian, Turkish, or otherwise can be relied upon to serve up some late-night fayre. Immigration to Northern Ireland did not really take off and uncannily there is a proliferation of Mexican Tacos, being served up in a number of late-night locations in Belfast. College students and late-night drinkers on either side of the sectarian divide queue up, as their differences dissolve and they bond over their love for deep fried fish and chicken Tacos, drenched in chili sauce.

Northern Ireland is not without its problems, the overstretched healthcare system, where waiting times to see a doctor can be longer than an advent calendar, are reported to be the worst in the UK. Add to that Brexit and the difficulty in trade with both the mainland and the rest of Ireland, has resulted in a political stalemate for over a year. But in comparison to its recent past, these are first world problems. As the population gets older and wiser, just like a married couple who have been together for a number of years, both sides have learnt to pick their arguments and a peaceful house is far better than a divided one, where as our taxi driver from the airport reminded us, each party is only interested in killing the other. As societies become increasingly concentrated with older people, the hope is in the pursuit of greater happiness, fighting for beliefs and thought systems will become a relic of the past and access to good hospitals and education will become the focus for the present.