Finance & Democracy

Wednesday, 23 July 2025By Chris Yapp

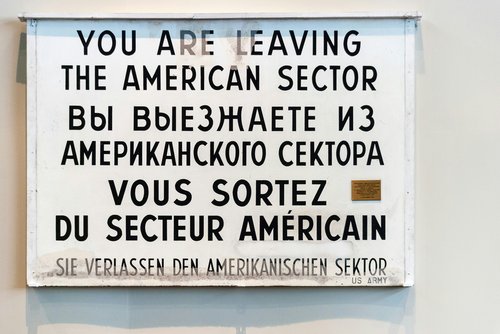

In the immediate aftermath of the fall of the Berlin Wall, there was significant optimism that Russia and the former soviet states would become democracies. The superiority of the market system and liberal democratic societies was seen as a given. Francis Fukuyama even went as far as to call it the “End of History”.

In particular, free and open economies were the route to technological superiority and innovation. The rise of the Internet and the World Wide Web promised a new dawn. Inequality was the price of a dynamic economy.

How has that worked out?

In the last few weeks, I’ve read a number of reports about Electric Vehicles and also AI that have described the rise of China leading to a new 'Sputnik moment' for the USA and western economies.

When Sputnik was launched back in 1957, the US assumption of superiority was severely tested. The US response was to increase the science budget. Today, the USA is cutting its science budget. Yes, the private sector investments are enormous, but they are largely not investing in the next generation science that will build the next generations of business.

At the same time we are seeing decreased confidence in democratic governments ability to deliver for their citizens and the rise of “strong men” leaders and populist parties.

If the view of the future from the 1990s was overoptimistic, my concern is that our current view of the state of the world risks becoming over pessimistic. I’m not arguing that there is no justification for pessimism. Indeed, on current trajectories I think China will become dominant in EVs and in AI over the next decade. The risks of escalating conflict and climate change are serious. These are uncertain times.

What I believe is needed is to understand the underlying assumptions that fuelled the 1990s exuberance and think seriously what needs to change to reinvigorate democracy and build the western economies for our current challenges.

In my last post, I argued that there was a strong tendency to overlook strategically the third sector as an agent of social and economic change. Here I want to look at the challenges to finance strategically with the current state of democratic societies.

The 1990s dominant mindset in the west was the rolling back of the state and increasing the role of the private sector. It was widely argued that if the rich got richer, the poor would get richer (trickle-down economics) and that public investment crowded out private investment.

Many UK consultants and Finance people went out to Eastern Europe and showed them how to sell off state assets and create market economies.

What happened was that this created oligarchies and entrenched corruption. That was not supposed to happen.

Elon Musk has claimed that it was his money that won the election for Trump. Whether you believe that or not, many do and the sense of democracy being for sale has become part of the disillusionment narrative.

However, for me the biggest problem for the future of democracy is agency. When you cast a vote does it and can it make a difference?

It is here that the rolling back of the state has faced its greatest challenge. Let me illustrate with an example. In the early days of austerity, I was involved in a number of workshops that provided much food for thought. One example was a Local Authority who had outsourced their call centre to save money and was now faced with further cuts. The solution was to further outsource to a centre many miles away. The side effects were significant. First, the savings proved largely illusory. Without local knowledge, call times to address problems increased, eating significantly into proposed savings. Also, for every £1 saved it was estimated that it took £1.30 out of local expenditure, a negative multiplier as those delivering the service weren’t spending locally.

The largest visible case in the UK is probably the state of water. The extent to which elected officials can address public experience of high bills, poor service and declining infrastructure when the investments in the UK are subject to the dividend needs of overseas pension funds, as one example, creates a sense of powerlessness in the electorate.

A visit to Finch Foundry in Devon, a National Trust property, was a lesson in how much has changed over a longer period, going back to Victorian times. I was shown around by a local whose family had lived in the area over many generations. He was able to talk using examples from his family and other families still in the locality. The earnings of the different grades were recorded. The owner had a weekly income of less than twice his senior workers and around 4 times the apprentices. All lived locally and would occasionally frequent the same pubs (some are still there!) Today, the owner of a business would not just live in a different village, county, country or continent, but the wage differentials are now in the 100s.

People working in the City institutions understand the importance of place. London is a “global village” yet in the UK and many other countries the sense of belonging and civic pride in many communities has been ruptured in the last 40 years or more.

So what do I think a modern dynamic economy and democratic society needs to do?

Here is my starter for 10!

1) Invest in place and the people who live there.

2) Governance structures that create agency for the citizens and business

3) Public, Private and Third Sector strategic engagement

4) Pro-competitive policy.

It is the last that I want to expand on. I think we need to move beyond price-based competition and look at competition on service and quality. It is here that I think the third sector can make a big difference. We need to take anti-trust seriously again.

Over the last 2 generations, we have seen technological and economic change impacting on blue and white-collar workers. The current wave is impacting the professional classes I heard a comment recently that America was in danger of forgetting that what made it great was the size of the middle class. I think there’s a lot in that observation. If the middle class stagnates or worse I think it’s likely that the pessimists will be proven right.

No-one ever put it better than “We have nothing to fear but fear itself”. It’s time for a new deal!