EC Consultation On Long-Term Investment - EFFAS Draft Responses

Wednesday, 22 May 2013By Con Keating

As you probably know, the European Commission recently launched a consultation on the Green paper on the long-term financing of the European economy. The deadline for the consultation is 25 June 2013.

Con Keating is currently preparing a submission on behalf of the European Federation of Financial Analysts Societies (EFFAS) addressing the 30 questions included in the consultation.

By sharing the draft responses to each question on Long Finance, he welcomes questions, comments and criticisms beyond EFFAS' traditional audience. Download EFFAS draft submission or read below EFFAS draft responses to the questions asked in the consultation. Please do not hesitate to leave a comment here.

1. Do you agree with the analysis set out in the Green Paper (p.4-5) regarding the supply and characteristics of long-term financing?

We do not agree fully with the analysis presented; it is incomplete in a number of aspects. However, we do not believe that an extensive critique is productive, but will point these differences out in our other responses, wherever in our opinion they are material. Our responses are, in the interest of brevity, sketches rather than detailed implementation plans.

We feel that the following quotation from Colin Mayer serves well to give context to our responses to these questions:

"This combination of shareholder interests, contracts, reputation, regulation and state engagement underpins the structure of economies around the world. It is the basis of national and international policies of domestic and global public institutions, When and where markets fail, there is a need for more regulation and state engagement; where state organisations malfunction, the privatisation and more liberal markets are required. This economic and political consensus emerged progressively towards the end of the 20th century and is now widely accepted. However, it has serious defects. Equally misconceived is the alternative, unconventional paradigm that advocates a private sector approach to the problem –‘corporate social responsibility’, Social entrepreneurship’, and ‘stakeholder values’. These see the fundamental problem as lying with companies and markets, and a need to reposition both to broader social agenda. They seek to realign them by altering the objectives of companies and markets. Where they fail is in establishing credible criteria by which these objectives can be delivered and in ensuring an alignment of the interests of socially conscious people with the priorities of their wider communities. The failure of the conventional and unconventional paradigms is in providing a compelling description of the corporation."

This viewpoint conditions our responses and the various proposals we put forward.

We are particularly concerned that the paper is single-minded; there are competing demands for capital, notably from households (for housing), together with governments (for investment) and the private sector, over which we would have concerns about potential unintended consequences – particularly over the question of ‘crowding out’. We believe that it is difficult to discuss long-term financing without touching upon the conflict between short-termism and long-termism as outlooks. In that context there is one significant area where we believe the coverage in the analysis is inadequate and it is an area that should be expected to feed into the responses to this consultation. This concerns short-termism and its role in fostering institutional corruption. This is a strand of research emanating from the Edmund Safra Centre for Ethics at Harvard University. The seminal paper is Lawrence Lessig’s “Institutional Corruptions”. In particular, we would draw attention to Malcolm Salter’s recent paper: “Short-Termism At Its Worst: How Short-Termism Invites Corruption… and What to Do About It”. We quote from the abstract of that paper:

“The central concern is that short-termism discourages long-term investments, threatening the performance of both individual firms and the U.S. economy. I argue, in this paper, that short-termism also invites institutional corruption. Institutional corruption in the present context refers to institutionally supported behaviour that, while not necessarily unlawful, erodes public trust and undermines a company’s legitimate processes, core values, and capacity to achieve espoused goals. Institutional corruption in business typically entails gaming society’s laws and regulations, tolerating conflicts of interest, and persistently violating accepted norms of fairness, among other things.”

Though US-centric, we feel that there are many insights and lessons to be learned from these publications which may transfer to the European context and long-term investment.

References:

- Mayer, Colin - Firm Commitment, OUP, 2013

- Lessig, Lawrence - March 15, 2013 - "Institutional Corruptions" - Harvard University - Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics; Harvard Law School - Edmond J. Safra Working Papers, No. 1

- Salter, Malcolm S. - April 11, 2013 - “Short-Termism At Its Worst: How Short-Termism Invites Corruption… and What to Do About It” - HBS Negotiations, Organizations and Markets Unit

2. Do you have a view on the most appropriate definition of long-term financing?

We need to change our culture regarding the long-term and in particular its relationship to the short-term. All too often we still hear that clarion call of short-termism; that the long-term is simply a compounding of lots of short terms, so that the only required focus is to take care of the short term and the long-term will simply derive from it. Most often reflected in the single-minded emphasis on quarterly returns in the stock market and within the fund management industry, this attitude largely misses the point. With such an attitude, would Boeing ever have designed the Jumbo jet? So, the most important aspect of any definition of long-term financing is the definition of long-term.

As we will see below, “long-term” has a number of attributes: we first focus on the simple, temporal one.

We can start by establishing a floor in the definition: long-term must mean longer than 20 years (i.e. longer than a generation). We would suggest that there is no real need to establish a ceiling to the definition, because there is none. For example, there should be no end to the period during which motorways and bridges are maintained: and that maintenance requires long-term funding. When the US Interstate Highway System was built under President Eisenhower, the Federal Highway Act included the establishment of a Highway Trust Fund, funded by hypothecated tax receipts on petrol. Such a fund should have no end while there are still cars using the highways but, in an all too typical example of the short-termism that we deplore, the US Congress has repeatedly refused even to tie the tax rate to inflation. Any consideration of the long-term must recognise that there is much in our political system which supports short-termism. This example should highlight the value of a long-term view, and the folly of a short-term one (at least in this instance).

Certain projects of value to the commonwealth (such as hospitals and universities, or roads and bridges) have no maturity date: the long-term for them is forever. They should be funded in a similar manner, and the hypothecation of specific taxes is not the only way. Capital markets have, in the past, been happy to issue and buy undated, perpetual bond issues, and this was not confined just to government issuers (the Canadian Pacific 4% issue springs to mind). Equally some of the players mentioned above, and in particular some charities and many universities and colleges can take particularly long-term positions on the back of particularly long-term views: Balliol College in Oxford is celebrating its 750th anniversary this year (which is a full 220 years older than the world’s oldest bank still in existence). The sources of long-term funding exist, and so does the demand.

We are reminded of the presence of cathedrals and churches that grace so many European cities – the financing, so many centuries ago, of their construction raises more than a passing resemblance to current issues, and perhaps even extends to aspects of institutional organisation. The sales of corrodies (a pension taking the form of board and accommodation) were notable in this regard.

We have emphasised the extreme of what we mean by long-term, and long-term financing, and are fully aware that the supply and demand of long-term funds will be for periods shorter than forever. However, it is important that we not impose any arbitrary constraints on our views. In brief, long-term financing is financing for at least one generation, and with a possible maturity date of forever. We will discuss later some of the inter-generational issues.

But there is more to long-term financing than the issue of time. In their work, the OECD have associated long-term investment with patient, productive and engaged capital. It is clear that time alone does not define the long-term. We note that the question refers to financing rather than investment, but will draw out some important though broader distinctions.

The patient, productive and engaged attributes are, we believe, symptomatic of the long-term rather than causal or defining. For example, many observers consider mortgage finance to be concerned, inherently, with long-term investment. This is undoubtedly true in the case of new construction; there it meets the OECD productive criterion. However, the majority of mortgage finance is concerned with the purchase of components of the existing stock (previously occupied housing); this is, in the owner-occupied case, the long-term financing of housing consumption rather than housing investment . In many European countries, the consumer attitude to owner-occupied housing is that it is investment, and it is the subject of much speculation. In a consumption context, of course, this is not the case and low rather than high prices are then preferred. We recently heard a variant to this in the context of the UK NEST pensions savings, where the recent rises in stock market prices was welcomed. However, the auto-enrolment system is expected to generate some £11 billion of annual contributions when the system is fully operational; these savers should prefer to buy their investments at low, not high prices. This is also relevant in the context of arguments with respect to intergenerational inequity. We return to this issue later.

This housing finance example raises a question of purpose; in this case, in the use of the financing. We believe there is a similar issue of purpose with respect to the source of the financing. Savings can have many different motivations or sources, from the relatively short-term to the extremely long. This can be from saving for some specific near-term purpose, such as the purchase of a car or holiday, to the extremely long-term of pensions and inheritance bequests on death.

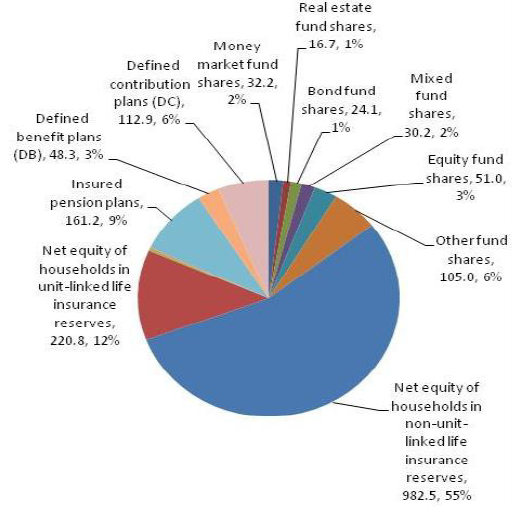

One of the widespread failings of current national statistics is that volumes of savings that are measured and published, but there is little or no discussion of, or data on, the term profile of these savings. This term profile absence is true, also, of the usage of these finances – though the recent estimates of infrastructure and climate change investment demands are a good starting point. We would like to see not just estimates of the volume of savings and investment demand, but also their term structure.

This interest in the term structure is directly relevant to the role and ability of markets and banks to perform the maturity transformation that resolves inter-temporal imbalances between supply and demand. We discuss a related concern with traded equity markets later. Liquidity is a critical issue with any maturity transformation – the ability to refinance when a deposit is called in the case of a bank, and the ability to sell a security at some future time in the case of a market. Financing which relies upon inter-temporal transformation should be expected to be more expensive than financing which does not, precisely because it is reliant upon liquidity conditions, which have a cost.

With this in mind, we should like to propose another (and complementary) method by which we may distinguish the short from the long-term; the source of liquidity from which the contract will derive its performance. Here, we would define the long-term as reliance upon the obligor of the contract as the source of the cash-flow liquidity, both before and at expiration of the contract. By contrast, we would classify reliance upon the market as the source of liquidity as short-term and speculative.

In this view, the purchase of a treasury bill and its retention until maturity would be long-term, as would the purchase of listed equity that is held solely for the collection of dividends. A life insurance policy is non-negotiable and relies upon the life company obligor for performance. A characteristic of the long-term is that income is the dominant concern in performance, which contrasts with the short-term where price behaviour is almost all-important. It is also notable that the high volatility, which characterises short-term behaviour in financial markets, converges slowly to the relatively low volatility of fundamental performance and growth when long-term horizons are considered.

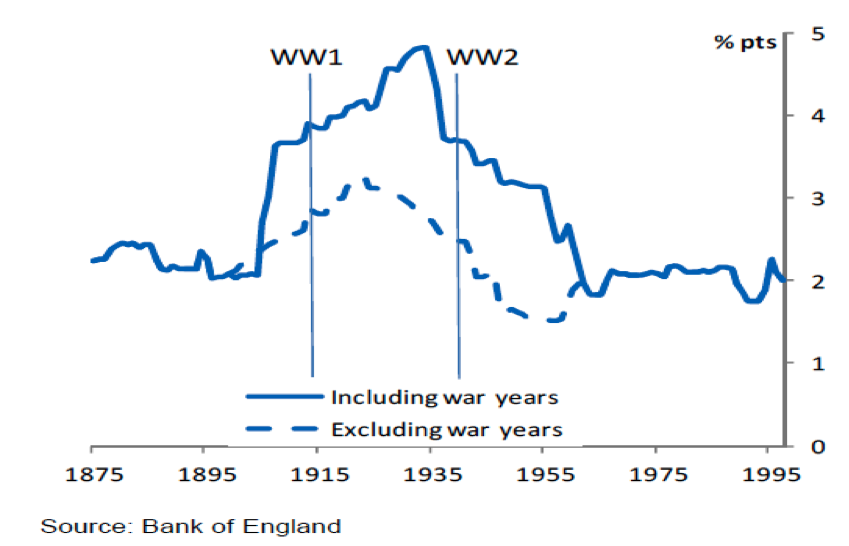

It is as well to remember how low this long-term variability (or risk) has been. The diagram below is reproduced from a recent Bank of England speech. Formally, this is the standard deviation of rolling 30-year periods of annual GDP growth.

It is clear that there are many shades of grey in this liquidity distinction. The speculations of high frequency trading are clearly short-term and the fifty year zero coupon gilt held to maturity is clearly long-term. However, in between, there are many differing degrees of dependency upon obligor versus market sources of liquidity. There are degrees of implicit preference that arise from this source of liquidity approach. The source of liquidity for an industrial enterprise may be entirely independent of the financial markets, sourced entirely in the sales of its products. The source of liquidity for contracts with financial institutions is usually predominantly financial markets. However, the non-negotiability of many consumer financial contracts serves to reduce the dependence of these institutions upon the markets, and incidentally exposes mark to market accounting standards as being inappropriate for these institutions. Here, the risk issue is not whether the instrument can be negotiated or sold to others, but whether the contract can be negotiated with the institution itself, such as deposits called from a bank.

It should also be recognised that financial institutions may add value in manners which are not replicable by an individual. The maturity transformation of banks might be replicated by an individual operating in traded securities; the bank, however, has an advantage with respect to the information it has with respect to its loan customers. However, there are many forms of collective organisation, insurance companies, DB pension schemes and mutual funds, which offer risk-pooling and risk-sharing advantages that are not replicable by an individual. This is the source of ‘financial depth’, and one of its consequences is that, if efficient, it will lower the aggregate need for savings. This suggests that savings targets should be specific to the economy and its financial infrastructure. It also suggests that there should be diversity in the form of ownership of these institutions.

The concept of replication figures prominently in market consistent accounting. Liabilities are replicated by traded assets. This rather begs the question: if an insurance or pension contract can be replicated by traded assets, why do these institutions, insurance companies and pension funds exist at all? Reliance upon the contract can be seen as ‘patient’ investment. We have some concerns over the ‘engaged’ aspect. We would prefer the concept of committed. Engagement in practice often means no more that lobbying management for higher dividends and immediate performance, with a thinly veiled threat of exit by sale in the market. The long-term investor is committed, for the term of the contract in the case of complete non-negotiability. This is the case in many savings contracts. We shall return later to issues of commitment and the control rights associated with the long-term.

It should be recognised that the long-term is already effectively defined in much regulation. This is most obvious in the case of (long-term) capital gains taxes. The application of preferential rates of taxation with holding term and purpose has been widely utilised within Europe to provide incentives for specific forms of investment. It is not obvious to what extent these incentives have been successful, or whether they have been cost-effective, let alone optimal. There are also many implicit issues within other financial sector regulation, for example: the risk weights applicable to long dated bonds, or even the setting of insurance risk margins from a ‘hedged’ base position within Solvency II.

It is, of course, also possible to define the long-term in terms of business cycles. In the mid-20th century, Schumpeter and others proposed a typology of business cycles according to their periodicity, to which names have been appended:

- The Kitchin inventory cycle of 3–5 years (after Joseph Kitchin);

- The Juglar fixed investment cycle of 7–11 years (often identified as 'the' business cycle);

- The Kuznets infrastructural investment cycle of 15–25 years (after Simon Kuznets also called building cycle]);

- The Kondratiev wave or long technological cycle of 45–60 years (after Nikolai Kondratiev).

One of the attractions of this type of approach is that it would be simple to distinguish between some of the classification issues evident in the Green Paper. This relates to the term structure of demand for capital investment by users, for example, the role of R&D (discussed later) in the fixed investment and long technological cycles. Finally, we would point out that some long-term pensions and savings entities have already declared their view of the long-term; in Canada, ten years has been chosen, while the Singapore GIC considers the long-term to be 20 years and more.

3. Given the evolving nature of the banking sector, going forward, what role do you see for banks in the channelling of financing to long-term investments?

Of their nature, traditional deposit-taking commercial banks are ill-suited to execute maturity transformations for long-term periods of the type we have used to define long-term above (i.e. from 20 years to forever). We have long held that the best way to minimise overall risk in the banking system is to recognise that there are numerous types of lending, expertise in which is not fungible. Thus, trade lending is not the same as mortgage lending, and consumer credit lending is not comparable to long-term project lending. In particular, whilst we recognise that there is a very valid and constructive role for securitisation within the financial system, that role should be played mainly by the capital markets and less so by the banks (and there should be a clear distinction drawn between them).

We perceive that one of the lesser-discussed contributing issues of the recent financial crisis was the lack of heterogeneity among the business and operating models of banks. This was competition beyond competence and informational advantage. Studies by Standard & Poors indicate that the banking sector has historically provided more than 60% of infrastructure financing while pensions, insurance and asset managers have supplied slightly less than 20%. We also note that capital market financing has been small relative to bank debt – approximately one tenth.

There have, of course, been specialised long-term credit banks (particularly in Japan, where they existed within a very structured banking system), and it is not impossible to create a system which includes specialised long-term credit institution. Having specialised institutions of one kind in the banking system does raise the question as to whether or not banks should specialise in a small number of areas in which they have specialised expertise, such as shipping and project finance, or trade finance or mortgages. This question is beyond the scope of this response, but it should be noted that the creation of specialised long-term investment banks has implications for possible changes elsewhere in the banking system. The initial performance of the UK Green Investment Bank, which has already disbursed more than €700 million, suggests that specialist institutions may rapidly acquire momentum.

Long-term credit banks are encouraged to fund largely through the capital markets, with issuance of long-term bonds. With the pressures on banks to improve their capital and liquidity ratios, the prospects for increases in bank lending on the scale necessary to accommodate the projected increases in infrastructure do not appear good. It also seems unlikely that they would be able to increase the degree of longer-term debt financing in their overall capital funding on the scale necessary to maintain the current maturity transformation mismatch, let alone reduce it.

It should also be realised that the long-term investment sector will not be able to increase its capabilities in infrastructure finance to substitute for banking on the scale necessary. Its principal constraint would not necessarily be capital, though the four-fold increase required if banks do not increase their lending, would be extremely challenging. The obstacle would be human resources, the limited supply of the necessary skilled and experienced staff. The investment could most easily increase its exposure to capital market instruments.

If the ring-fencing or creation of utility banks with a retail mandate occurs and is sustained, these banks would likely operate as brokers and advisors for their clientele in capital markets; their role as conduit rather than principal. The asset management industry can be expected to create specialist retail infrastructure investment funds and distribution through the retail banking system could be expected – however, the level of demand for these is highly uncertain.

4. How could the role of national and multilateral development banks best support the financing of long-term investment? Is there scope for greater coordination between these banks in the pursuit of EU policy goals? How could financial instruments under the EU budget better support the financing of long-term investment in sustainable growth?

The way to best support the financing of long-term investment and the pursuit of EU policy goals (inasmuch as these involve long-term investment) through multilateral and national development banks is to encourage the latter to further develop the depth and maturities of the liabilities that they issue to finance themselves. These could include far more securities with targeted investor bases and far from the simple, homogenous, fungible instruments of benchmarks and active trading markets. This could include such things as deferred term annuities or bonds with sinking funds and active amortisations. This could also include securities or instruments offered directly to individuals, and include non-negotiable instruments.

It is arguable that the EIB is a significantly better credit than any of the member states of the EU, its shareholders. Given the likely increased demand for safe assets from the banking sector (for capital and liquidity purposes) and from the derivatives sector (for the collateral requirements of CCPs), there is more scope than ever for the advantageous issuance of securities to satisfy these demands. Here, there is a question for these shareholders of how much maturity transformation it is desirable to undertake within these institutions. It would seem that there is a role for the commercial banks as originators of infrastructure debt and as suppliers of liquidity insurance to securitisations of this debt. However, many of the characteristics of infrastructure finance, such as the construction risk, are idiosyncratic and not readily amenable to securitisation. There is also the question of the level of retention, a necessity for the management of the moral hazard inherent in the originate and distribute model of securitisation. On this retention issue, we would suggest that it should be possible to have retentions which declined with the passage of time.

Multilateral and national development banks should co-ordinate their liability management and engage in ever-closer cooperation when it comes to funding long-term infrastructural projects. One way to confirm that there would be economies (of whatever nature) to be gained from increased co-operation would be to encourage the formation of working parties between official institutions to determine where to find such economies and how to exploit them. Later, we recommend the formation of a new infrastructure financing institution. This could be organised as a bank, but equally it might be an asset manager or even insurance company – in fact, a hybrid institution would seem to be optimal.

Survey work by Standard & Poors on infrastructure projects suggest that multilateral institutions account for only 3% of total financing, smaller than governments at 9% and only marginally higher that the export credit agencies. We would suggest that the EC should,

- Verify the truth of this estimate, and

- Establish the reasons for it.

Prior to the 2007-2008, much infrastructure financing was greatly facilitated by indemnity cover supplied by the mono-line credit insurers. In fact, these companies originated in the US municipal market, where much of the longer dated issuance was infrastructure investment related. We suggest later that a specialist infrastructure bank should be created, which we envisage would actively supply the guarantees and indemnities. On a technical note, we would suggest that these should be of subrogation form, where the bank would step in assuming coupon and principal payment responsibilities, rather than financial guarantee, where capital sums are exchanged immediately.

In our other responses, we indicate the potential for the issuance of deferred term annuities. Many investors have expressed concern over the risks of the construction phase of projects and have avoided financing this phase. We wonder if guarantees from the development banks might resolve this issue; however, we would indicate this is an area for further thought rather than an explicit recommendation on our part.

5. Are there other public policy tools and frameworks that can support the financing of long-term investment?

There are complementary policies and broader frameworks that would support the financing of long-term investment.

We will begin by noting that investment in the context of the Green Paper includes both research and development expenditure (R&D) and capital investment. We find it helpful to consider R&D as being concerned with the investigation of options and flexibilities available to the institution while capital investment is the exercise of those options. This difference alone suggests that different financing methods are appropriate. External debt finance is unlikely to be available for R&D simply because, in and of itself, R&D does not deliver future revenues that may be pledged, even implicitly, to creditors. We note that there is already an EC objective of raising R&D expenditures to 3%, with two thirds of this being financed by the private sector, from the (approximately) 1% of today.

There is a school of thought that, in Europe, current R&D expenditures are overly focussed upon increasing the operational productivity of existing processes and not adequately upon the types of innovation that might prove more useful in recovery from recession. If that is indeed the case, then R&D expenditures need to be refocused on areas which are less geared to proving real but short-lived productivity benefits to existing processes, towards a less certain but potentially much more productive . Foe example, according to President Obama, the US Government’s investment in the Human Genome project is expected to have a return of 140:1. In terms of the cycles mentioned earlier, this is the long Kondratiev cycle of technological change. These innovations are now frequently referred to as disruptive technologies, and can be very important in terms of employment, wages and questions of social inequality. It seems likely that these will prove important in the coming decades.

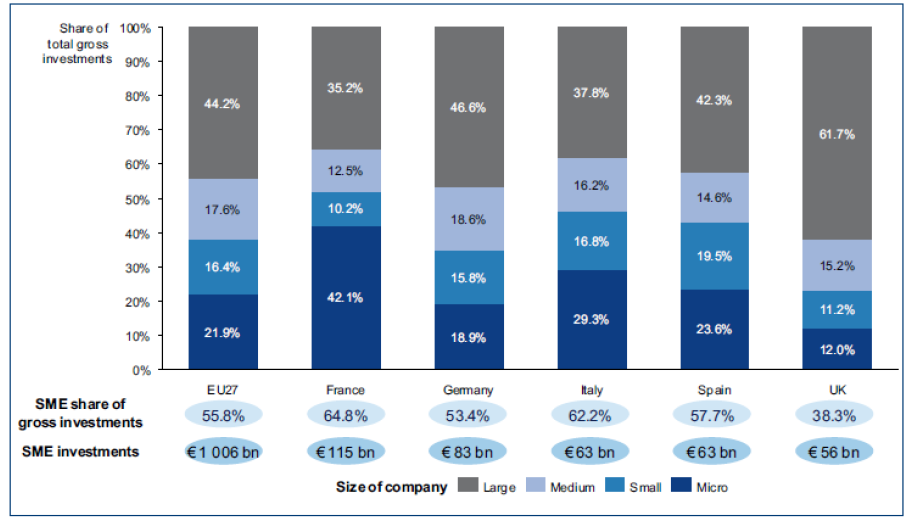

The majority of investment in the EU economies is undertaken by the corporate sector (in this response, we use the expression corporate sector to include partnerships and unincorporated bodies). As several of the later responses make clear, it is critical to remove any impediments to the corporate sector participating in investments. This applies both to the taxation treatment of financing and to procurement policies. This is particularly important in the current situation. We would also note that the post crisis fall in private investment in the EU27 was extremely substantial (€300 billion plus) and far more important than the fall in private consumption. We would also note that private investment has historically been about six times as large as government investment.

We note that the paper is concerned with external finance, while most corporate investment in fact utilises internally generated funds. We would also note that the corporate sector is currently extremely well positioned to increase investment as its cash holdings, counting only listed companies, now exceed €0.75 trillion. In Europe, 40% or more of long-term investment is financed by corporations, with government typically accounting for volumes that are in the 25%-35% range. The balance is accounted for by households. The European corporate sector’s reliance upon external finance is relatively modest –averaging in the 30%-35% range in France and Germany and slightly higher, 45%-50% in the UK.

The rate of internal generation of funds by the corporate sector can be improved upon. For example, through the increased use of book-reserve pension schemes – these can be structured and insured to offer efficient and secure pensions to employees, while reducing the dependence of the corporate sector on external (mainly bank) funding. Funded DB pensions, by contrast, constitute a material drain upon the cash resources of their corporate sponsors in the countries where these are prevalent – in large part, this is exacerbated by regulation and accounting issues. They are inefficient because of

- Regulation, and

- Management expenses, to the extent that a corporate sponsor is better off simply offering cash wages to employees.

These regulations also introduce considerable uncertainty over future cash flow expense, which can only serve to lower current investment as companies prefer to hoard cash in difficult times. We would also note that DB pensions function as automatic stabilisers, while the alternate, DC arrangements, are intrinsically pro-cyclical.

Differences in the taxation treatment of various forms of pension should be eliminated. More traditional tools, such as, capital allowances and depreciation regimes, can be utilised for more targeted purposes in the corporate sector. One specific taxation variant that should be considered and costed would be the exemption from taxes of qualifying corporate infrastructure financing securities. We would see this occurring in conjunction with the elimination, more generally, of the deductibility of interest expense (see later). This could also perhaps extend to the issuance by corporates of qualifying securities where the income/coupons were exempt from income taxes in the hands of the investor.

Public Sector Infrastructure Agency

However, the most important range of policy options and instruments lies with the public sector. A specific infrastructure agency seems appropriate – largely to separate these activities from the issues of social policy and transfer financing. It might be hoped that this would break the association between government and low productivity growth. It is also clear that the predicted demands for investment far exceed the rather limited previous levels of government investment, and that capacity constraints arising from current limited government capabilities might well apply. This agency would be financed, not by government, but by capital markets. It should have the ability to issue tax-exempt securities, much in the manner of the US municipal market. Among the securities, we would expect it to issue, are perpetual income notes and deferred annuities. This would be the body, not sovereign states, extending guarantees and, in other ways, facilitating the external finance of infrastructure projects, both under government and its own ownership, and also in the private sector more generally.

Longer-dated Debt Issuance by Governments

One further policy shift might also be considered. Currently debt management offices issue the majority of government debt securities as “benchmark” issues in order to capture the liquidity premium as a cost advantage. This feeds into very active trading of government debt and a market culture that can only be considered short-term. It is, perhaps, superior for the debt management offices to issue targeted long-dated issues for long-term institutions, such as pension funds and insurers. Among these securities, we would envisage perpetuals and term annuities, including deferred annuities. It seems to us that there is a natural fit with deferred annuities for projects which have long construction phases before any usage revenues (real or imputed) become available.

Infrastructure Commissioning

On a more immediate note, it is evident that there are many current impediments which could be removed – individually minor, but collectively important. The fragmented nature of infrastructure commissioning among divisions of government and a lack of consistency in bid evaluation techniques and requirements is one. In this regard, the Laidlaw Inquiry (on the UK West Coast Line) conclusions are helpful as a guide to good practice: (a) ensuring future franchise competitions are delivered at a good pace based on sound planning, a clear timeline, rigorous management, and the right quality assurance; (b) creating a simpler and clearer structure and governance process for rail franchise competitions, including the appointment of a single director general with responsibility for all rail policy and franchising; and (c) ensuring we have the right mix of professional skills, in-house, and where necessary from professional external advisers.

The fragmented nature of the commissioning authorities carries the consequence that some of these have very weak credit quality. In elementary credit, it is often the case that the credit quality is considered of any entity is considered to be limited by the framework within which it is embedded. For example, many consider corporate credit ratings to be upper bounded , in principle, by the credit standing of the sovereign. While we do not subscribe to this simplistic analysis, we would note that the EU Project Bond Initiative proposes only credit enhancement of the project company financial structure. Both the letter of credit and subordinated debt approaches of the EIB operate within the capital structure of the project vehicle. While this may enhance the credit standing of that vehicle to levels acceptable to investors, it may not be the economically efficient route. In our opinion, the EU/EIB Project Bond Initiative should also consider offering credit enhancement to commissioning authorities. We note that many of the problematic private finance projects in the UK have had their difficulties rooted in the inability of the commissioning authority, the schools and hospitals, to continue to meet their debt service obligations while maintaining the quality and quantity of their primary functions.

Cross-border Impediments

There are also some residual cross-border impediments, such as the presence of withholding taxes in some cases – it appears that double-taxation treaties are being rigidly interpreted. To cite one example, a German Kapitalanlagegesellschaft (KAG), a common form of organisation of pension and other funds, is still subject to withholding tax on Belgian interest income. There are other withholding tax issues. It should be realised that the presence of withholding taxes and their administrative burden is a major drawback in an investment context, and particularly so for long-term investments.

It should be remembered that there are three areas of regulation that are relevant for potential policy action. The frameworks for infrastructure development, PPP or other, together with investment and financial markets, and the prudential regulation of the investment institutions are all relevant. In common with the OECD, we would see the task as being to create supportive scaffold across all three areas.

6. To what extent and how can institutional investors play a greater role in the changing landscape of long-term financing?

It may be useful to preface our response, with some published comments of Carolyn Ervin, a director in the Financial and Enterprise Affairs division of the OECD:

"So why don’t institutional investors live up to their long-term investing potential? Several complex and interlocking barriers hold them back....

"Institutional investors increasingly rely on passive investing or indexing on the one hand and alternative investments (such as hedge funds) on the other. The former can discourage them from being active share-owners while the latter may involve shorter term, higher turnover investment strategies.

"Agency problems are another barrier to long-term investment. Pension funds in particular rely increasingly on external asset managers and consultants for much of their investment activity. However, they often fail to direct and oversee external managers effectively - handing out mandates and monitoring performance over short time periods which introduces misaligned incentives into the investment chain. Institutional investors also contribute indirectly to short-termism via some common investment activities, such as securities lending or increasing investment in Exchange Trade Funds (ETFs). Investors may, therefore, be inadvertently contributing to speculative trading activities in the very securities that they own.

"Government regulation can also exacerbate the focus on short-term performance, especially when assets and liabilities are valued referencing market prices. For example, the use of market prices for calculating pension assets and liabilities (especially the application of spot discount rates) and the implementation of quantitative, risk-based funding requirements appear to have aggravated pro-cyclicality in pension fund investments during the 2008 financial crisis in some countries."

Different institutional investors have different goals, and these imply different horizons. Money-market funds may be institutional investors, but we should not expect them to purchase significant amounts of undated perpetual securities. At the other end of the spectrum, there are institutional investors whose horizons are indeed undated: university and college endowment funds and perpetual charities, for example, may take extremely long views in their investment portfolios. In the middle we may find pension funds and life companies, whose investment horizons will lie somewhere betwixt the two extremes, but may well have horizons of beyond 40 years.

The first way for these investors to play a greater role is to engage them in free discussion of their needs: it is only by recognising an institutional need for a particular type of investment that one can innovate productively. We would emphasise that this is engagement with institutions rather than their advisors and intermediaries. It should be recognised two of the principal long-term investor classes, pension funds and insurance companies are severely restricted by prudential regulation. Here we consider current accounting standards to be part of regulation. It is interesting to note that this prudential regulation is concerned principally with investor protection and, correctly, only to a minor extent with systemic stability. This is unbalanced; it does not consider the benefits, the positive externalities associated with the activities curtailed or prescribed.

Institutional investors, particularly pension funds, are currently poorly served by fund managers and investment advisors, whose advice is conflicted and often short-term in nature. In much the same way that a trader wants ever greater liquidity and trading, these firms have an interest in promoting the short-term, expedient and complex. Extending explicit fiduciary responsibility to them will greatly assist their institutional clients fulfil the long-term elements of their tasks.

The most important things that can be done for institutional investors is to remove the impediments which prevent these investors from pursuing their preferred investment habitats. These are overwhelmingly regulatory in nature.

The Green Paper considers a number of different forms of investment, for example, green and sustainable, infrastructure (among which are a multitude of types of investment) and SME finance. We do not find this helpful as the differences between these can be large and material for the manner in which they are intermediated. It seems to us that much of SME finance need is not long-term in nature. The predominance of competitive tender processes in the public-private model of infrastructure finance make this very different from the standard investment management model of insurance companies and pension funds. With standard investment, the pension fund or insurance company is concerned with the evaluation of an investment proposition presented to it. This is, in fact, how most green and sustainable investment propositions are marketed. The high costs and low probability of success of these infrastructure bidding processes are deeply problematic for insurance companies and pension funds. Indeed, it is possible to argue that this is trading, an activity that is explicitly penalised by the UK tax authorities for pension funds.

The risk profile of these investments is also unlike that of more traditional investments. With traditional investment, risk grows with time; the concerns expressed by institutional investors over consistency of political commitment and regulatory stability are similar in nature. However, the concerns over procurement and construction costs for infrastructure, the high failure rate of new and small companies (fifty percent of newly incorporated firms do not survive their fifth birthday in the UK), and uncertainties over the viability of green and sustainable investments at scale in the absence of subsidies add a new dimension. Here the risk is loaded onto the short-term rather than growing with time.

The question of developing a larger market for institutional private placement for debt securities is under investigation by the Association of Corporate Treasurers at the request of the UK Business Bank. This market would hold the prospect of lower volatility of prices as valuation could be based upon economic fundamentals rather than market prices.

7. How can prudential objectives and the desire to support long-term financing best be balanced in the design and implementation of the respective prudential rules for insurers, reinsurers and pension funds, such as IORPs?

The problem currently lies with the present form of prudential regulation that has simply been erroneous in writing across from banking a form of risk-based regulation that does not recognise the different nature of long-term institutions (and that failed even for banks when tested). One of the distinctions that should be drawn is in the role of maturity transformation.

For an institution, such as a bank, maturity transformation as a viable business strategy is dependent upon future funding availability. If the loan is negotiable, it may alternately be sold. If the deposit advanced in a loan is subsequently called, it must be replaced. In the case of markets, there is a similar maturity transformation role - the equity or bond, bought in the expectation of exit and realisation by sale in the market at the future then-prevailing price, are obvious examples. In fact, if an asset cannot be priced in a market, it is usually impossible to use it as collateral in, for example, repo financing. In this regard, we would draw attention to the fact that the August 9 2007 ECB intervention in markets, which most regard as the seminal event of the crisis, was triggered by the inability of a bank to price securities in several collective investment funds. In this regard, bank funding (liquidity risk) and market liquidity are closely related concepts. This is a material risk and correctly a prudential concern.

Insurers and long-term assets

Stylistically we may describe banks as having liquid liabilities and illiquid assets, while insurance companies have illiquid liabilities and liquid assets. However, there really is no reason for any requirement for long-term insurance institutions to hold liquid assets. This may be prudent in the case of general insurers where substantial claims (or liabilities) may become payable at short notice, but for most classes of long-term business this is not true.

For an institution that has liabilities that are long-term in nature, there need be no such maturity transformation risk. For example, an insurance company may hold (even unlisted) equity among its assets up to the amount of its own equity and retained earnings without having any maturity transformation exposure. It is also important to understand that many of these long-term institutions are not exposed to market risks – their liabilities cannot be subject to a ‘run’ in the manner of bank depositors. Surrender terms, where there are any, are typically punitive. In the long-term, prices should be immaterial to these investors – income and fundamentals dominate the security of their liability contracts. The relevant consideration is the gap between asset cash flow maturities and the equivalent liabilities.

Prudential Regulations

Prudential regulation is risk-based; the value and accuracy of these risk estimates have been widely questioned. The regulatory imposed risk weights have also been widely, and validly criticised. The point which has not received as much attention is that the remedy under these risk based systems is unique – extra capital buffers or provisions, currently held. We would point out that one of the few things we know (with certainty) about risk is that it means that more things may occur in the future, than will. The consequence of this is that it is only too easy to over-provide, which will limit the efficiency of the institution and the savings they represent. We would point out that these buffers may be needed only in the future, which suggests that provision today may be time-inefficient. In fact, the standard solution to this problem in other situations is insurance – we routinely insure against fire, flood and other risks. We would stress the point that it is perfectly possible for a financial institution to self- insure against future risks through the structure and form of its asset portfolio. Such institutional insurance arises from future non-market cash-flow, but is rarely if ever recognised in the market prices of the institutions. We would emphasise that the current and proposed regulation of banks, insurers and pension schemes is a monoculture – and a monoculture that is firmly rooted in the here and now of market prices and current buffers. This is a source of systemic instability.

Accounting Standards

This is greatly compounded by current accounting standards (see later). It is nonsensical that current regulatory standards focus upon the present position with respect to the institution’s solvency. For long-term institutions, the composition of the assets held is all-important with respect to the ability of these institutions to discharge their obligations in full and on time in the future when they fall due. Under the current standards, an institution may hold exclusively cash again the present value of liabilities and be considered sound. However, it is clear that, without earnings that are at least equal to the discount rate applied to actual liabilities, the institution will be unable to discharge these fully and on time as they fall due. The approach in regulatory use may be described as balance sheet insolvency when the reality in markets is equitable insolvency. This latter form requires the existence of an uncured payment default, before acceleration occurs. To use discount rates derived from market prices or yields is inappropriate, but it is part of the current regulatory valuation process.

The accounting standards are also mixed attribute in nature. Assets are valued at market prices, while liabilities are discounted present values. These introduce material bias and volatility into pension and insurance accounts which is unreal – the bias and volatility are an artefact of the accounting measurement system rather than of the institutions being measured. Above all, when setting the level of prudence required, regulation should recognise the benefits that will be foregone. For example, insolvency for DB pension schemes has been a rare event, but their regulation in pursuit of pensioner protection has effectively closed this form of pension provision, which has served millions of pensioners very well over many decades. The substitutes now offered – DC arrangements – are massively inferior and in a number of respects may be economically harmful. There are further questions that need to be considered when inefficient forms of saving are adopted, particularly when these savings are tax advantaged.

Other Concerns

We are also concerned that regulation across different types of institution can be inconsistent. In this regard, we would point out that, for banks, the absence of long-term liabilities is penalised, while for insurers it is their presence.

8. What are the barriers to creating pooled investment vehicles? Could platforms be developed at the EU level?

In most product categories, residents of the various member states are faced with markedly different marketplaces in terms of the product offering, prices, costs as well as the availability and nature of information. There is clearly a tax and regulatory-induced home bias. There has been some consolidation among market intermediaries, but that has raised more competition issues than it has reduced fragmentation across states.

Investors are not able to access similar products in all member states. Some product providers, operating in an inherently national regulatory framework, are prevented from offering similar products in other member states. There are concerns over a lack of comparable information and insufficient transparency about fees and costs, as well as limits to the transferability of savings/investments from one product/provider to another (exit fees, legal barriers).

The question of transferability is much misunderstood. For example, the question of pensions transfers where the question of transferability is known as portability. The primary concern in many cases in not portability but in fact preservation. There really is little or no need for a pension literally to follow the member, what is required is preservation of the accrued benefits.

Transferability is hardly problematic when the pension has individual DC form, as this is, prior to retirement, little more than a tax advantaged savings scheme. For DB schemes by contrast, there may be material differences between schemes and any transfer process more complex to achieve equitably. We feel that the detail of these issues and particularly the question of a common platform should be the subject of a separate consultation, as they are not confined to long-term investment.

9. What other options and instruments could be considered to enhance the capacity of banks and institutional investors to channel long-term finance?

We have already indicated the use of tax-exempt securities or contracts, but there are many other methods. These all involve forms of risk sharing or risk-pooling among individuals and with the institution. Mutual organisation has much to recommend it in this regard.

It is important that long-term contracts participate in the performance of the institution or the economy. The ‘with-profits’ policy of pension and life insurance was a classic contract design. Similarly, the traditional UK defined benefit pension scheme was a very efficient form of contract design – highly suited to purpose from the perspective of the beneficiary.

These institutions enhance the financial depth of an economy, which here means that fewer savings are required, to achieve a specific objective, than might be the case in their absence. They also reduce the need for an ongoing individual involvement, though the individual is fully committed.

We would suggest that market consistent accounting and regulation, which rely upon implicit or explicit replication, would be deficient in this regard. Bundles of market-traded securities cannot be expected to reflect the synergies of risk pooling and risk sharing which are contractually possible within and with such institutions. Put another way, these forms of institution exist because their contracts cannot be replicated in other ways.

We would expect the proposed ring-fenced and utility banks that will be dealing with retail depositors to operate as both advisor and broker of mutual funds and direct investments to their wealthier depositor clients.

10. Are there any cumulative impacts of current and planned prudential reforms on the level and cyclicality of aggregate long-term investment and how significant are they? How could any impact be best addressed?

It is almost impossible to exaggerate the cumulative effects of current regulation, which includes, for these purposes, current accounting standards for long-term liabilities and investment. Proposed regulation might, not unfairly, be described as more of the same. It has had dramatic effects on the degree of pro-cyclical activity. Not only should we be concerned with explicit institutional fire sales, there is a more important question of the conditioning of the markets.

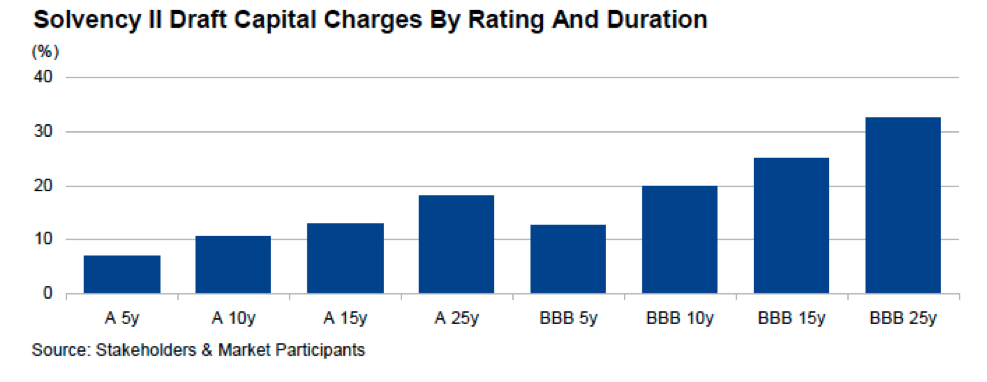

EDHEC Business School studied the effects of the proposed Solvency II regulations on bond fund management for insurance companies extensively. As can be seen from the illustration below , there are significant capital costs associated with bonds that increase markedly with declining credit quality and with increasing term. The magnitude of these risk weights will serve both to limit the amount of debt finance available and provide an underpinning to its cost.

The asset allocations of long-term insurance companies and of many pension funds have moved markedly towards more bonds and other instruments that lie well below their optimal or design risk tolerance and risk-bearing capacity. These investment policies are acutely limiting the terms of many consumer contracts, such as annuities.

Derivatives instruments, which, it should be remembered, are contracts inside of the financial services industry, have found wide usage in response to regulatory pressures. They can be expected to have little effect upon outside activity, including investment, beyond the rents charged, so effectively, upon them by the financial services sector.

Even at the level of institutional design, procyclicality is induced. The shift to individual DC pensions is an illustration. Traditional DB is contra-cyclical; it provides automatic stabiliser effects to the economy. DC, by contrast, is actively pro-cyclical. Behaviour induced by individual wealth effects matter in the case of individual DC – including the lowering of interest rates in response to declines in economic activity. Though many regulators have stated they are exercising forbearance with respect to the funding status of pension funds, the fact is that many schemes have been required to lower benefits, for example, in the Netherlands, or contribute much more (UK). In the UK, some life insurance companies have been required to lower equity asset allocations to satisfy their regulator.

The Anomaly of Liability Mark-to-Market

One present accounting nonsense is that the liabilities of an institution decline in line with the market price of their obligations. The classic illustration of this was the “profits” taken by major investment banks during and after the crisis, when their continuing existence and service of their debt obligations was in doubt. Unless the body has bought back these obligations at their discounted price, the obligation to service and repay those obligations is unchanged by their market price. The obligation is a function of the terms on which the liability was incurred by the institution. The market price reflects also the likelihood that the company may not make those payments as well as the state of liquidity in the market in which they are traded. The concern for the institution is with meeting the terms and conditions under which the obligation was created. This is a question of its own current and future liquidity. Perhaps it is easier to see this in another context. The payments an individual must make under the terms of their mortgage do not decline (or increase) with the market price of mortgages securities.

The mixed attribute nature of pension accounting is also a concern – the use of market based discounted present values for liabilities and market prices for assets leads to biased and incorrect results. This was investigated in depth in a 2013 paper by Keating, Settergren and Slater entitled Keep your lid on!. That paper illustrates the way in which a form of amortised cost accounting may be applied to DB pension schemes in a manner that is fair value consistent. The paper also demonstrates that market consistency is not fair value consistent. It is notable that the International Association of Insurance Supervisors’ 2011 Insurance Core Principles, Standards, Guidance and Assessment Methodology states in Section 14.0.4 which deals with valuation that: “An economic basis may include amortised cost valuations and market-consistent valuations”.

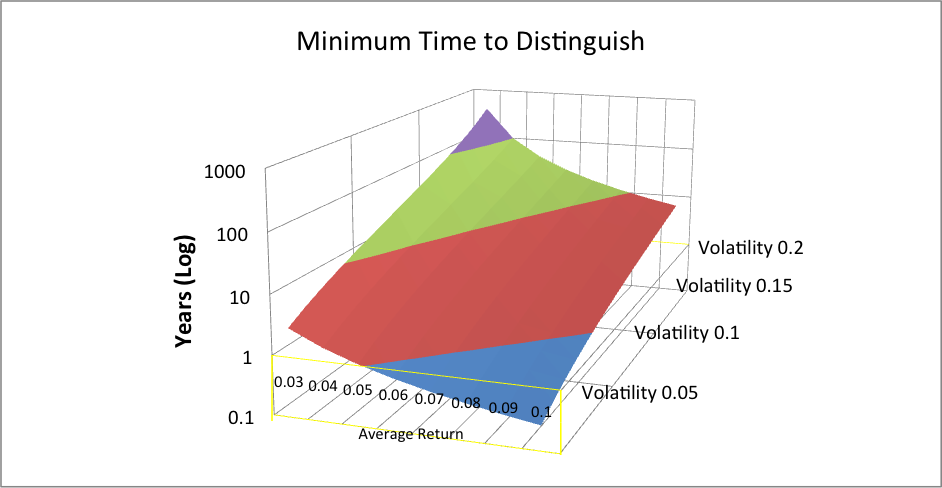

We would also contend that market prices constitute a very poor basis for decision and that the concept of market discipline, a feature of most regulatory systems, is badly flawed in respect. The critique is that the signal in market prices, which is relevant to long-term fundamentals, cannot be distinguished from the noise. We have illustrated this point (using a simplifying assumption of normality of returns) for ranges of return and noise on an annual basis, showing the number of years at which the signal will be equal to the noise – only in the light blue area is the signal greater than the noise. Moreover, when market prices are dominated by short-term participants, we should expect that market discipline will reflect their preferences rather than the preferences of long-term investors or holders.

This question of incorrect signals from market actions is directly observable. The RBS take-over, which proved so disastrous subsequently, was explicitly and resoundingly approved by voting shareholders.

We are repeatedly cautioned that we should not read too much into particular outcomes in most other aspects of our daily lives, but here, we have precisely the opposite being required by accounting standards and much regulation. It is particularly pernicious in that the academic hypothesis, which attributes so much to market prices, has the universal ‘get-out’ clause that these prices reflect or discount some risk or other, which of course is unobservable. It is not a testable, and possibly falsifiable, financial theory. The related question of forecast errors is accessibly, and well covered in an eponymously named speech by Ben Broadbent, of the Bank of England’s MPC.

11. How could capital market financing of long-term investment be improved in Europe?

Currently equity capital markets do not constitute a meaningful source of new finance for private sector investment; they are more important as mechanisms by which existing entrepreneurs may realise their interests. They now serve (poorly) as (costly) governance mechanisms. By contrast, the debt capital markets are important sources of finance for industry and government. Recently, this has been extended to smaller companies by exchange based listing and trading of debt securities. Retail investors are reportedly active in these markets.

The Role of Credit Rating Agencies

We note the role of credit rating agencies (CRA) in debt security evaluation and their inclusion in the regulatory regimes of financial institutions. We feel that these requirements – for securities to be rated – should be eliminated. These requirements give the ratings agencies a role in determining access to markets, without concomitant responsibilities and duties. Rating should be an entirely voluntary exercise on the part of an issuer – a decision to be taken in the context of costs of issuance with and without such ratings. With adequate disclosure standards ratings agencies are entirely redundant. It is also a mistake for such ratings to be used in the risk evaluation of investment funds. Some have noted that this is a problem of collective organisation and have suggested that individual provision, with products such as DC ‘pensions’, may be superior. All that is achieves is an attitude of ‘après moi, le deluge’ and extremely volatile unstable financial markets. The greater issue is not the defects of particular forms of collective organisation, but rather that of the resulting co-ordination failure.

The Generational Problem in Pension Funds

The greatest issue in equity markets is one of governance. Many reports, such as Kay and Cox, have highlighted this. Here, we would not want to leave the impression that we believe that governance is the most important driver of corporate behaviour; that, of course, is competition.

The governance question, in essence, is one of the tragedy of the commons, where distinct generations have different incentives with respect to usage. This can be illustrated in the context of pension funds. Here the members close to or in retirement have a greater interest in preserving capital values rather than risking their entitlements alongside younger members – particularly when a scheme is underfunded. Wrongly, many have taken this to be an argument for extremely conservative management of pension funds. As with a two generation commons problem, the solution is to offer differential control rights. In the case of the pension fund, giving control (or weight) to the younger generation will align the generational interests. The beneficiaries who have the claims the most remote in time should have the greatest proportional say. The younger generation will wish to accept sufficient risk to achieve their objective of receiving the promised pension, but will not take excessive risk as this would simply result not only in harm to current pensioners but destroy their own property. This is a balancing act to be performed by scheme trustees. In the case of corporate occupational schemes, there is also the position with respect to the sponsor to be considered.

There is a related issue of trust versus contract. The superiority of systems based upon trust can be demonstrated at the macro-level by the superior returns (usually) achieved by trust rather than contract based pension schemes.

Rewarding Long-Term Equity Investors

Differential control rights, or voting entitlements that increase in the length of ownership could go far in aligning shareholder interest in the long-term. This is not simple to achieve in voting rights for traded securities, but is feasible from an incentive standpoint in dividends and other distributions.

The Trend Away From Equity Markets by Long-term Investors

The current state of markets is poorly understood. The average savings institutional holding period has not declined as dramatically as might be construed from overall market turnover, which has increased manifold. What is happening here is that the trading activity in the ‘free-float’ of equity securities has multiplied incredibly. Much of this has been the result of the advent of high frequency trading. It should be realised that trading or the need for the option to trade is a sign of a lack of commitment.

The UK serves, perhaps, as an illustration of recent trends. According to the Office for National Statistics, UK equity holdings of insurance companies have fallen from 20.8% of the London market in 1991 to 8.6% in 2010 and for pension funds the situation is even more pronounced – from 31.3% down to 5.1%. Unless these long-term holders have been replaced by other long-term holders, the London stock market has become a venue for far more maturity transformation than was previously the case.

The Erosion of Trust and the Rise of Algorithmic Trading

There is a related issue – that long-term holders sell some or all of their holdings to short-term speculators and “arbitrageurs” when take-overs or bids emerge. These short-term actors usually have an interest in ensuring that the bid or other transaction ultimately occurs. We see this behaviour on the part of long-term institutions as being motivated by a desire or need to participate in short-term performance – for example, under third party mandates awarded to them. Selling by long-term institutions should not be considered as unwise or even anti-social, given the radical nature of these changes and indeed, the rather dismal track record of successful mergers and acquisitions.

It is clear that trust in market fairness has broken down – many institutional investors now utilise algorithms to execute their market activity precisely because they have lost trust in their ability to do this without exploitation. This market impact facet of institutional activity is a significant contributor to the effective costs of portfolio management . There is also a further effect. Markets that are dominated by short-term noise traders, of which computer-based algorithmic traders are a form, will be less efficient than markets where this is not the case. The informed investor will dominate activity in the less liquid stocks. The highly liquid actively-traded stocks will tend to converge more slowly than these illiquid stocks to fundamentals.

It is true that there is a role for market-making intermediaries to overcome the problems of outside order imbalance – usually referred to as liquidity provision. However, it is also true that too much liquidity may be available. It is notable that the liquidity provision role offered as defence by the high frequency traders does not address why it is that they do not dedicate their capital to liquidity in the low liquidity stocks, where the premium is highest but rather focus upon stocks those that are already liquid. Equally it does not address why liquidity dries up instantaneously whenever there is any sign of market stress or distress. There are a number of practices associated with high frequency trading which we would like to see suppressed. For example, the practice of entering literally thousands of orders with the intent of withdrawing these unexecuted gives a false impression of the depth of a market. A financial non-transactions tax would reduce or eliminate these.

12. How can capital markets help fill the equity gap in Europe? What should change in the way market-based intermediation operates to ensure that the financing can better flow to long-term investments, better support the financing of long-term investment in economically-, socially- and environmentally-sustainable growth and ensuring adequate protection for investors and consumers?

Capital markets will have difficulty filling the equity gap. As long as regulation favours debt over equity in portfolio allocations, this will not occur. Similarly, as long as the tax treatment of interest cost favours debt issuance, corporations will offer debt securities.

In fact, the equity gap is most pronounced in early stage investment and this is where the information asymmetries are largest. Indeed, there is much that is speculative about the start-up and early development phases of most businesses. It is not at all obvious that these start-up companies have any natural role in the construction or operation of infrastructure although they may do so in ‘green’ and sustainable fields – in, for example, spin-offs from university research. However, the information asymmetry issues will severely restrict the utility of incurring the additional costs of seeking public listing. These ventures are best handled in private bilateral negotiations. In many jurisdictions, there are already tax incentives in place to facilitate these. It is possible that further pooled vehicles could be created which would mitigate many of the information asymmetry problems, and indeed that many such as the UK EIS and Venture Capital Trusts (the European VCT appears a good start here) already exist.

We believe that one of the problems of regulation is that the voice of intermediaries and their trade associations has been loudest and most strident, and has overwhelmed the voice of long-term investors. The intermediary community have a natural interest in exchange, not investment: this is intrinsically short-term.

13. What are the pros and cons of developing a more harmonised framework for covered bonds? What elements could compose this framework?

This survey of the covered bond market within the context of the question focuses greatly on specific recommendations. In the interest of space we have been parsimonious in our reply, but can expand at length on any specific question if asked.

European covered bond legislation has been the global standard setter for this asset class. In order to revive this position after European covered bonds (originally a AA+/AAA asset class) lost some global market confidence, some harmonization and improvements are necessary. To ensure affordable mortgages, broad cross border investor acceptance of covered bonds is necessary not only within the EU, but globally. Good covered bond legislation and regulation should be easy to evaluate by both domestic and foreign investors.

The mortgage bonds of Fanny Mae and Freddy Mac bonds are not only the global competitors to European covered bonds. The concept of a centralised refinancing hub for mortgages with an implicit government guarantee similar to FannyMae and FreddyMac has been proposed. From a market development and regulatory point of view, the alternative is the decentralized, high quality legislation with many competing market participants. Part of the question is therefore, how much harmonization is required to compete successfully against the centralized US model in the global fixed income market?

Some diversity of covered bond legislation across Europe offers investors a choice. Full harmonization could lead to a US-style centralized model, which would probably not be able to compete well with the US institutions and their track record of full government support. However, too much diversity makes the analysis of the assets too complicated and rather costly. The core areas of harmonization that should be considered are:

- Eligible Assets.

Core to the market should be the traditional mortgage covered bonds and, although currently out of fashion, public finance covered bonds. A standard definition of a public loan would help here. The composition, whether to combine mortgages and public loans in one cover pool and whether to add other long-term assets, should not be harmonised as this enhances diversity. - LTV calculation/ LTV limits / Over-collateralisation.

LTV calculations differ across countries. These differences can be difficult for investors to evaluate- a harmonised approach is warranted. This applies also to the classification of assets. Harmonization would hardly harm local markets and would make a cross-country comparison easier. Currently covered bonds of, for example, France, Spain and Germany are not comparable based on the available information about the underlying mortgages. This is highly important for commercial property loans.

Overcollateralization is a crucial issue. Standard rules should apply across all European legislations. Same LTV calculation, same LTV limits, same overcollateralisation. This would make bonds comparable across countries, which they are currently not (or only by applying complicated models and simulations of the "critical" non-performing loan levels and critical loss-given default levels).

There is no reason why LTVs for residential mortgages are limited to 60% in Germany and 80% in Spain. One possible suggestion would be to apply a limit of 80% for residential housing and 60% for commercial property, while at the same time using the 102% over-collateralisation.

Given the current stance of the rating agencies, a AA+/AAA covered bond market probably would require an over-collateralisation of 106-110% (depending on the rating of the senior bank debt). Note that we have reservations about any regulated role for ratings agencies. However, such high levels might be too restrictive and inflexible for any legislation; particularly when the equity ratios of banks should be much higher in future and their senior debt ratings improved. - Alternative Assets.

The alternative assets or substitute assets allowed within a covered pool are needed in order to manage the Net Asset Values, the liquidity and other characteristics to ensure that the pool matches the characteristics of outstanding bonds to a high degree. However, the kind of assets and the amount allowed differs significantly between the different European legislations.

One proposal would limit the amount of alternative assets to 10% of the cover pool rather than 15% or 20%, as is currently the case in some countries. Derivatives, both their quality and quantity, have been the focus of recent attention by the rating agencies and their models, but legislation is neglecting them.

The notional amount of derivatives, as well as the share of the NAV, should be limited in the same fashion across countries. Variable rate loans should be refinancing on a variable basis and not on a fixed basis. Although investors do prefer fixed rate bonds and borrowers prefer variable rate loans, any mismatch can amount to a huge structural risk. If they are not limited, cover pools could become too dependent on senior bank obligations (counterparty risk) in extreme market environments. This question needs to be examined in the context of overall bank interest rate mismatches. - Legal position of the cover pool.

All assets in a covered pool should be registered and be separable in case of a bank default or the case of any bail-in.

All cover pools should have the same position as the obligor bank in the situation of a bank default or a bail-in in order to ensure the pool’s ongoing liquidity through ECB refinancing operations. - Transparency.

Semi-annual reporting of the covered pool quality should be based on the current German model. In addition: more transparency on the composition of alternative assets is necessary (e.g. what kind of assets, issuers, countries etc.) and on the composition of any derivatives in the pools. A lack of transparency in France and Spain has been the cause of covered bonds there being priced on perceptions of their governments’ willingness and ability to bail them out.

The central argument for more harmonized covered bond legislation is that the quality of the asset base should determine the market price, and only to a minor extent the quality of the issuer, and to an even smaller degree the legal domicile the issuing bank and its legislation. Currently, market prices are determined in the exact opposite order. This situation is a market distortion, which needs to be addressed by regulators and legislation to ensure the optimal functioning of the market.

It may also prove desirable to offer incentives to the buyers of newly constructed homes and, perhaps, to first time buyers through the securitisation structures of these mortgages.

14. How could the securitisation market in the EU be revived in order to achieve the right balance between financial stability and the need to improve maturity transformation by the financial system?

Clearly, securitisation has a place in European capital market in the future. The constrained lending capacity of the banking system alone is sufficient reason. However, the experience of the crisis with this type of investment is fresh in the memories of many investment institutions, and it will take a long time to overcome this.

The ‘originate to distribute’ model was undoubtedly viable, though subject to moral hazard. This can be overcome by retention of a significant first loss exposure by the originating institution. This is the equivalent to the ‘deductible’ of standard insurance policy pricing.

There is a second issue, which concerns the level of maturity transformation inherent in the financial structure of the securitisation. This often depends upon the presence of significant levels of financial engineering with respect to liquidity provision within the service structure and with respect to maturities. From a systemic standpoint, these securitisations may constitute a material level of risk, and of course, these engineering derivatives contracts create contagion between financial institutions and markets.