All-In Finance Against Carbon Initiative (Or Take The 'C' Out Of 'ESG')

Tuesday, 25 July 2023By Michael Mainelli

Proposal

There is an opportunity to present a refreshed, united front on the way to use the totality of global finance to stop greenhouse gas emissions. The re-emphasis would be on:

- making ETS markets work;

- setting standards and targets for government issuance of sovereign sustainability-linked bonds;

- using insurance-issued performance bonds to establish the credibility of voluntary carbon markets;

- building international public-private catastrophe reinsurance vehicles.

This article sets out how we might create an internationally-recognised financial architecture framework which governments should aspire to implement nationally.

Background

UN COP is the Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), commonly referred to as the UNFCCC COP. This annual gathering focuses on global efforts to address climate change and implement measures outlined in the UNFCCC, such as reducing greenhouse gas emissions, adapting to the impacts of climate change, and providing financial and technological support to developing countries.

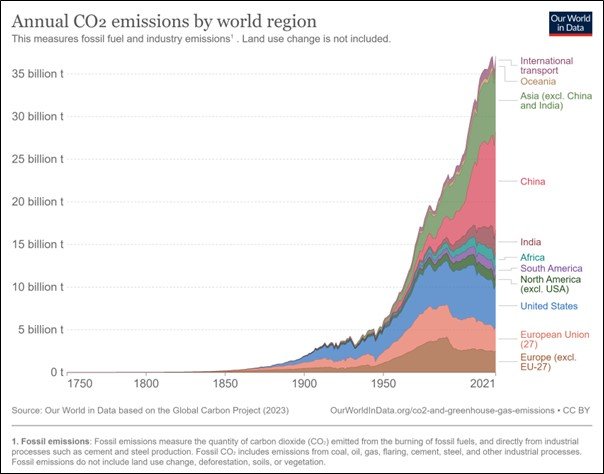

The ultimate objective of the Framework Convention, as stated in 1992, is “stabilization of greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic [i.e., human-caused] interference with the climate system”. Despite efforts from the first conference (COP1) held in 1995 in Berlin, annual global greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise and, though they may have stabilised on a per capita basis, show little sign of falling soon. In short, the Framework Convention is not yet working. COP28 will be held in the United Arab Emirates from Thursday, 30 November till Tuesday, 12 December 2023.

We Know What To Do, Just Not How To Do It In Time

Reducing global greenhouse gas emissions requires a combination of economic and social mechanisms that drive sustainable practices and promote the transition to a low-carbon economy, such as:

- Carbon Pricing: Implementing a carbon/greenhouse gas pricing mechanism, such as a carbon tax or cap-and-trade system, creates economic incentives for businesses and individuals to reduce their carbon footprint. By putting a price on carbon emissions, it encourages the adoption of cleaner technologies and energy-efficient practices.

- Renewable Energy Incentives: Providing financial incentives and support for renewable energy sources, such as solar, wind, and hydroelectric power, can accelerate the shift away from fossil fuels. These incentives can include feed-in tariffs, tax credits, grants, and subsidies to make renewable energy more cost-competitive and attractive to investors.

- Energy Efficiency Programs: Implementing energy efficiency programs in industries, buildings, and transportation can significantly reduce CO2 emissions. This can involve setting efficiency standards, promoting energy audits, offering financial incentives for energy-efficient upgrades, and raising awareness about energy-saving practices.

- Sustainable Transportation: Encouraging the use of low-carbon transportation options, such as public transit, cycling, and electric vehicles (EVs), can help reduce emissions from the transportation sector. Policies that support EV adoption, expand charging infrastructure, and improve public transportation systems can be effective in this regard.

- Sustainable Land Use Practices: Encouraging sustainable land use practices, such as reforestation, afforestation, and the protection of natural habitats, can help absorb and store greenhouse gas from the atmosphere. Additionally, promoting sustainable agriculture practices that reduce emissions from deforestation, land degradation, and livestock production can contribute to emission reductions.

- Research and Development: Investing in research and development of clean technologies, energy storage systems, and carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies can facilitate the transition to a low-carbon economy. Innovation in these areas can drive technological advancements and cost reductions, making sustainable options more accessible.

- Public Awareness and Education: Educational campaigns, public outreach programs, and initiatives that promote behaviour change can empower individuals and communities to make sustainable choices in their daily lives.

- International Cooperation: International agreements, such as the Paris Agreement, promote coordination, knowledge sharing, and collective action to address climate change. By working together, countries can establish emission reduction targets, share best practices, and support each other.

A combination of these mechanisms, tailored to specific regional contexts, is typically needed to achieve significant and lasting reductions in global CO2 emissions. Additionally, policy stability, long-term planning, and consistent commitment from governments, businesses, and individuals are crucial for successful implementation.

Mechanisms 1 to 8 above are all moving ahead, yet reports conclude that the scale of finance is still paltry, e.g. “Only about 16% of climate finance needs are currently being met. To achieve net zero, public and private sector entities across the globe will need approximately $3.8 trillion in annual investment flows through 2025. But only a fraction of this capital is currently being deployed. Even when viewed with a wider lens that considers funding such as transition finance, expected needs still outweigh flows by 66%.” What Gets Measured Gets Financed: Climate Finance Funding Flows and Opportunities, Rockefeller Foundation & BCG (4 November 2022).

Back To Carbon

The third Conference of the Parties (COP3) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) took place in Kyoto, Japan, in 1997. The primary outcome of COP3 was the adoption of the Kyoto Protocol, an international treaty aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions and combating climate change. The key agreements reached at COP3 include:

- Binding Emissions Reduction Targets: The Kyoto Protocol established binding emissions reduction targets for developed countries, referred to as Annex I countries, for the period 2008-2012.

- Commitment Mechanisms: The Kyoto Protocol introduced three mechanisms to help countries meet their emissions reduction targets:

a) Emissions Trading: Countries could engage in emissions trading schemes (ETSs), allowing them to buy and sell emissions allowances to meet their targets. This mechanism aimed to create a market for emission reductions and promote cost-effective solutions.

b) Clean Development Mechanism (CDM): Annex I countries could invest in emission reduction projects in developing countries and receive credits for those reductions. This aimed to encourage sustainable development in developing nations while helping Annex I countries meet their targets.

c) Joint Implementation (JI): Annex I countries could implement emissions reduction projects jointly and receive credits for the reductions achieved. This was meant to encourage collaboration and technology transfer between developed countries.

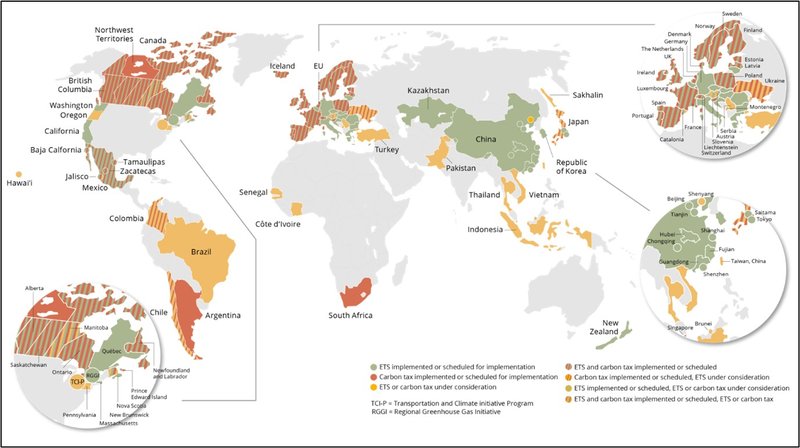

While the CDM and JI have struggled, credible ETSs now cover 23% of global emissions. A major breakthrough was the implementation of a Chinese ETS in 2021.

As most of these systems cover roughly 50% of their national or regional emissions, approximately 46% of emissions could be covered by achieving 100% coverage. Clearly COP28 could focus on moving to 100% coverage and 100% of nations having an ETS. Two of the larger outliers with no ETS are the USA (14% of global emissions) and India (7%).

ETSs can and do work, as shown round the world, once the permit issuance is restricted and the markets enforced.

Take The ‘C’ Out Of ‘ESG’ (... and yes, we can spell 'ESG')

Meanwhile, ESG has become, incorrectly, synonymous with preventing climate change. Rating agencies and consultancies are developing ESG scores for clients, for a wide variety of issues using a wide variety of algorithms. But as the MIT ‘Aggregate Confusion’ project found, companies could be in the top 5% on one ESG rating algorithm and the bottom 20% on another. And reputable firms like Shell find their ratings to be A from one rating agency and C+ from another. A recent issue of the Financial Times’s Responsible Investing supplement, FTfm, notes that “a lack of definitions and data is a sizeable obstacle to sustainable (ESG) investing”.

Advisors to financial services firms have been pushing ESG approaches hard, not least because ESG work generates fees. Yet the resulting clamour and confusion and costs have led to firms leaving capital markets for private sources of funding, thus negating the intended outcome that ESG strictures should increase the cost of capital for non-compliers. Good, legal, cashflow is valuable on unlisted markets too.

Taxonomic confusions have led to perverse roadmaps and blockages. The threat of litigation has led firms, e.g. major insurers, US-listed companies, to drop the targets altogether.

Social and governance issues are tangentially related to greenhouse gas emissions. Within ‘E’, there are many components that have market failures where ESG monitoring may help, e.g. forestry, water, biodiversity. However, ETSs can and do work. Perhaps the chant should be, “Take the ‘C’ out of ‘ESG’.

All-In Finance Against Carbon

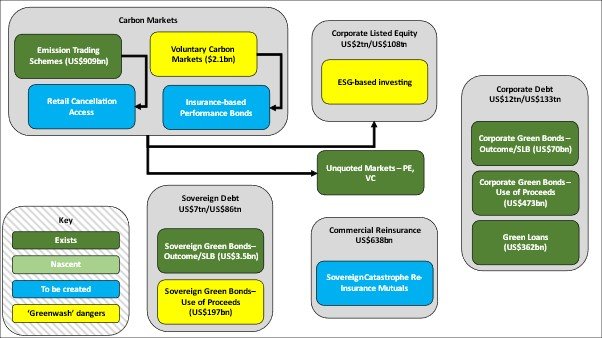

This paper’s proposal is to prepare for COP28 by submitting a much clearer financial compact combined with some straight talking, about carbon only. “We, the global financial services industry, can stop greenhouse gas emissions using markets, if governments commit to:

- making ETS markets work;

- setting standards and targets for government issuance of sovereign sustainability-linked bonds;

- using performance bonds to establish the credibility of voluntary carbon markets;

- building international public-private catastrophe reinsurance vehicles.

Perhaps call this ‘All-In Finance Against Carbon’ or ‘Extreme Finance To Save The Planet’. Behind this idea would be a ‘template’ for governments to use to ensure that their financial architecture meets the requirements for delivering net-zero 2050, e.g.:

- they have a functioning ETS that will cover 100% of emissions by 2040, and a commitment to a fixed date, ideally 2050, for net-zero emissions;

- they have issued X% of national debt in Y year stages, e.g. five years, against their net-zero emissions target using sovereign sustainability-linked bonds;

- they are working to build a voluntary carbon/sequestration market, but one backed by performance guarantee bonds;

- they are member of a critical national infrastructure catastrophe reinsurance mutual for climate change impact.

The diagram below attempts to summarise how this financial architecture might fit together.

Clearly, if there is interest in an All-In Finance Against Carbon compact, then there is much discussion ahead of COP28 and during the COP28 year. A sticking point will be those who wish to bring in many of the other ‘E’ items. While supporting the goals of wider sustainable finance, the sub-set of anti-carbon finance is the goal of the All-In Finance Against Carbon. Discussions would need to work towards:

- agreeing a draft architecture;

- agreeing draft compact;

- gaining pre-commitments to signatures from financial institutions;

- agreement from the hosts, the UAE, that this is in line with their goals;

- a methodology for discussion, iteration, and issuance.

Much has been made of the fact that 2024 is the 80th anniversary of Bretton Woods, where the world agreed on a new international monetary system. Some of the principles of Bretton Woods might have analogues that apply to this global crisis:

- Fixed Exchange Rates ≈ carbon prices are the medium of exchange;

- International Monetary Cooperation ≈ cooperating via the bond and reinsurance markets;

- Free Trade ≈ trying to ensure that carbon prices and bond rates factor into trade issues rather than regulation, e.g. if you are paying more for your sovereign sustainability-linked bond then that might set your tariff rate, not a government dictate;

- Economic Stability and Development ≈ strong carbon prices could well help developing nations pursue better development paths, and potentially have trade advantages (see 3);

- Sovereign Autonomy ≈ by agreeing to the compact and to the target template, governments remain autonomous in all other respects.

Conclusion

CFCs were solved by banning them. But there were existing alternatives to CFCs. SOX and NOX were solved largely by financial markets using markets, as there still needed to be some emissions. Greenhouse gases, as agreed at COP3, fall into a category similar to SOX and NOX – markets can fix this problem.

An All-In Finance Against Carbon compact is an ambitious goal. Frustration at the lack of progress and the numerous result-free jobs-for-the-ESG-boys-and-girls should lead to a desire to use grown-up, hard finance to solve the resource allocation and pollutant problems it has solved elsewhere.

Let’s talk.

Appendix A – Act Now: Climate Emergency Roadmap for the International Financial Architecture

Aviva Investor’s report, “Act Now: A Climate Emergency Roadmap for the International Financial Architecture” (October 2022), provides a summary and roadmap for transforming the international financial system to effectively address the challenges posed by climate change. The key points covered in the document are as follows:

- Climate Emergency: The document acknowledges the urgent need to address climate change as a global emergency and highlights the inadequacy of current financial systems in tackling this crisis.

- Limitations of Current Financial Architecture: The document points out that the existing international financial architecture lacks the necessary frameworks, mechanisms, and resources to adequately address climate-related risks and promote sustainable development.

- Roadmap for Transformation: The document proposes a roadmap for transforming the international financial architecture to align with climate goals. It outlines six key areas of action:

a) Climate Risk Assessment: Encouraging financial institutions to integrate climate risk assessments into their decision-making processes and disclosure frameworks. This includes assessing both physical and transition risks associated with climate change.

b) Macroprudential Regulation: Strengthening the role of regulators in addressing climate-related risks and incorporating climate stress testing into prudential frameworks to ensure financial stability.

c) Green Investment: Mobilizing capital towards green investments and sustainable projects by leveraging public and private finance. The document suggests measures such as green bonds, sustainable finance initiatives, and innovative financing mechanisms.

d) Carbon Pricing: Promoting the adoption of carbon pricing mechanisms globally to internalize the costs of carbon emissions and drive the transition to a low-carbon economy.

e) Sustainable Development: Integrating sustainability considerations into development finance and ensuring that infrastructure projects align with climate and environmental objectives.

f) International Cooperation: Enhancing international cooperation and coordination among financial institutions, governments, and regulatory bodies to address climate change collectively. This includes harmonizing standards, sharing best practices, and fostering information exchange.

- Key Stakeholders: The document emphasizes the importance of engagement and collaboration among various stakeholders, including governments, central banks, financial regulators, multilateral institutions, and private sector entities, to achieve the desired transformation of the financial architecture.

- Implementation Challenges: The document acknowledges the challenges associated with implementing the proposed roadmap, including political will, coordination, capacity building, and resource mobilization. It highlights the need for proactive action to overcome these barriers.

Overall, the document provides a comprehensive overview of the need for and potential steps to transform the international financial architecture to effectively address the climate emergency. It emphasizes the urgency of taking action and the importance of cooperation among global stakeholders to tackle climate-related risks and promote sustainable development.

Appendix B– The Principles Behind Bretton Woods

The principles used at the 1944 Bretton Woods Conference in New Hampshire, laid the foundation for the post-World War II international monetary system. The conference aimed to establish a framework for economic cooperation and stability among nations. The key principles adopted at Bretton Woods were:

- Fixed Exchange Rates: The conference established a system of fixed exchange rates, where participating countries would peg their currencies to the U.S. dollar. The U.S. dollar, in turn, would be convertible to gold at a fixed rate. This system aimed to promote stability and facilitate international trade by reducing currency fluctuations.

- International Monetary Cooperation: The conference emphasized the need for international monetary cooperation to prevent competitive devaluations and foster economic stability. Participating nations agreed to consult and coordinate their monetary policies to maintain exchange rate stability and promote balanced global economic growth.

- International Monetary Fund (IMF): the IMF's primary objectives included promoting exchange rate stability, facilitating international trade, and assisting member countries in achieving sustainable economic growth.

- World Bank: the World Bank provided financial support for post-war reconstruction and development projects in member countries, particularly in war-torn regions, later expanded to include poverty reduction and promoting economic development in developing nations.

- Free Trade: The Bretton Woods principles endorsed the importance of open and multilateral trade. The conference recognized the need to reduce trade barriers and promote the liberalization of international trade to foster economic growth and cooperation among nations. This principle laid the groundwork for later initiatives like the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and the World Trade Organization (WTO).

- Economic Stability and Development: The conference highlighted the significance of economic stability, full employment, and sustainable development as key objectives. The principles aimed to address the economic challenges faced by countries after the war and foster a cooperative approach to ensure shared prosperity and development worldwide.

10.Sovereign Autonomy: While promoting international economic cooperation, the Bretton Woods principles also respected the sovereignty of member nations. Countries retained control over their domestic monetary and fiscal policies while recognizing the need for coordination and consultation to maintain stability and avoid disruptive economic practices.

The principles agreed upon at the Bretton Woods Conference provided the framework for international economic cooperation and monetary stability for several decades.