A Vision Of Collective Defined Contribution Pensions

Friday, 24 November 2017By Con Keating

Recently the TUC published a study, commissioned from and executed by the Pensions Policy Institute, of the variability of Defined Contribution (DC) pension outcomes. They consider the fund performance and (annuitized) pension income for individuals retiring in each of the years 2000 – 2017. The results are rather stark. Pension pots have varied from £214,000 to £308,000, and the annuity income from £27,871 to as little as £14,484. The volatility of pot outcome was modest, just 11.2%, and that of annuity income 17.7%. The situation faced by an individual is actually worse than this – the study assumed benchmark performance for all, while the reality is that there will be considerable dispersion of performance across the various funds they have chosen as their investment vehicles; volatility greater than 11% is commonplace. As the TUC’s Tim Sharp observed: “Retirees are being increasingly faced with a blizzard of risks that are bringing new sources of uncertainty and chance into financial arrangements for old age.”

Collective Defined Contribution (CDC) schemes are an arrangement to mitigate this uncertainty by the pooling and sharing of risk among members. They are member mutual. They do not need any corporate sponsor – where these are workplace based, beyond making timely payment of contributions for new awards, there is no obligation or responsibility assumed by the employer. Though they may take a number of legal forms, the tradition of trust based arrangements in the pensions world makes this an obvious choice – with trustees elected by members and perhaps, from among them, and a small executive management group appointed by the trustees.

The member is 'promised' a pension accrual in similar manner to a Defined Benefit (DB) pension – say, 1.5% of final salary inflation indexed, or 1.75% Career Average Related Earnings (CARE), for each year of contributions. There is risk-sharing among members in this arrangement. It subsidises older members pensions at the expense of younger, when investment returns are good, and younger members at the expense of older when expected returns are low. The contribution made and this “promise” define the Contractual Accrual Rate (CAR) – the implicitly indicated investment return on contributions. The 'promised' pension ultimately payable is projected using standard actuarial techniques. These three terms, contribution, projected pension and CAR, define the equitable interest of a member in the scheme.

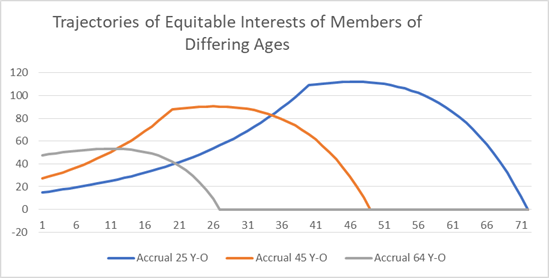

The equitable interests of three members, for a single contribution, and their trajectory over time is shown in Diagram 1, below:

The sum of the equitable interests of members, are equivalent to the scheme liabilities under a defined benefit arrangement. Projections are updated with the passage of time to reflect survival, experienced inflation and other relevant risk factors, and with that the equitable interests of any and all members.

The terms of the 'promise' for new awards are revisited from time to time by the trustees to ensure that it is in line with expected returns from financial markets – in other words, that it is offering ‘value for money’ to members. The ‘promise’ is not a guarantee; it is not inviolable. Indeed, the pension paid may be greater than this ‘promise’, not just lower. The pension paid in any year is determined by the value of the asset portfolio as a proportion of the equitable interest of the member. This is effectively a funding level. If assets have performed well this will result in higher than ‘promised’ pensions. This equitable share of funding arrangement would also ensure that members will receive a pension over their entire lifetimes – it will also allow the distribution of the member’s complete savings. There need not be any retentions for risk buffers or capital retentions, with their potentially stranded assets.

Members may transfer the asset equivalent of their equitable interest at any point in time, subject to the usual restrictions that they be into qualifying arrangements. Members may decide that they wish to enter a drawdown arrangement rather than the scheme default pension income arrangement. Taking a larger drawdown than that pension, determined by the funding level, will lower the member’s residual equitable interest in the scheme. Members may be admitted in either the accumulation or payment phase – such schemes could serve simply as decumulation vehicles.

The asset portfolio is subject to point-in-time price volatility. The CDC arrangement exposes only the current year’s pension to that risk. If a decreased payment is unacceptable to a pensioner, he or she may opt to top up that year’s pension payment at the cost of a lowering of their residual equitable interest going forward. Active contributing members may voluntarily chose to make additional contributions when the asset funding is less than complete; this would increase their equitable interest and restore the amount of pension payable.

As a multi-period investment arrangement, the scheme benefits from pound cost averaging when net cash flow positive (the sum of contributions and investment income less pensions payments and operating expenses) , but suffers the converse, sometimes colloquially referred to as ‘pound cost ravaging’, when net cash flow negative.

Many whistles and bells may be introduced - for example the scheme could operate as a provident fund, where borrowings are permitted from the fund for qualifying purposes, such as medical emergencies, house purchase and educational costs. This is also true of many of the other benefits associated with the traditional DB model, such as disability pensions.

Contrary to the assertions of some commentators, such schemes do not need huge numbers of members, though size does ensure risk-pooling has maximal effect. Nor do they need to commence with large numbers of members.

The complexity introduced through the concept of the member’s equitable interest is well within the capabilities of today’s technologies – and the absence of legacy systems is a positive in this regard. This technology could also serve as the primary information channel between trustees and scheme members.

There is one further way in which schemes might reduce asset volatility: by risk-pooling and risk-sharing the performance of part or all of their asset portfolios with other schemes.

CDC schemes are not exposed to sponsor insolvency risk. The concept of insolvency for a CDC scheme is vacuous in that these are merely obligations owed by members to themselves, and linked directly and equitably to the current asset value. There is absolutely no need for regulation, even though the proper concerns of trustees, unlike DB, would now include paying ‘promised’ pensions as they fall due.

The initial public problems with DB arose from an inequity – pensioners in payment had priority over active members. All of the regulation and interventions we have seen since have not resolved this problem fully and have introduced another set of inequities – in this case between the stakeholders of a firm. CDC, as envisaged in this article, resolves all of those issues.